For some time Italy has been threatening France’s dominant position as the UK’s favourite country when ordering wine in restaurants and bars. But now it has finally replaced it at number one, what does it have to do to stay there? Wine Business Solutions’ Peter McAtamney offers some answers.

The premium on-trade might have a lot of wine to sell, but what it does not have is a lot of data, research and analysis to give it a comprehensive understanding of how the sector is doing. One company that is focused on trying to shine a light on the key trends that are happening is Wine Business Solutions. What makes its research so interesting is that it is largely based on what wines are actually on restaurant wine lists. Not what people might like to sell, but the actual bottles they have in their cellars and store rooms to sell. It takes wines lists at random from restaurants and bars across the country (see footnote for split) and then weights the findings to get a national picture.

Its latest analysis of UK wine lists shows that Italy has overtaken France for the first time in terms of the share of total listings, coming in at just over a quarter at 26% compared to France at 24%. A small but significant gap. But it also shows a remarkable turnaround over the last year as the same study at the beginning of 2018 showed France to be well out in front at 29% share of listings, compared to Italy at 24%. So Italy’s success this year is also just as much about how much ground France has lost over the last 12 months.

But if you go back to 2014 and see that France had a mighty 32% share of wine lists compared to Italy’s 20%, then this clearly has not been a sudden change in fortunes, but a long, steady shift in power. Peter McAtamney explains why.

Why has Italy taken top place in the UK on-trade, overtaking France in the process?

As long ago as 2015 we started predicting this next step change in the wine market. I’m still shocked at how hard and fast that change occurred. In the US and Australia, it has been even more dramatic than the UK. In the UK the change in market leadership is also due to a lot of high-end French wine being delisted. The boom in Burgundy prices, particularly, came at the wrong time as far as the UK on-trade was concerned.

How do you explain the shift away from French wines?

The average consumer in the 90’s could handle one or two brands at best. In the 2000s, wine styles like Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Grigio and Pinot Noir started to be understood by the majority of consumers. In the 2010s the idea of provenance in terms of all things that we eat and drink became something that everyone could now grasp. Under that scenario, the French excelled. They invented the appellation system after all.

Now, there are consumers who are sophisticated enough to know that in countries like Italy there is a great heritage of traditional winemaking using little known varieties that is still being discovered and that is hugely exciting.

If you went into a restaurant in the UK in the 1980’s, wine lists would have Chablis, Sancerre, Bordeaux etc and they might not even say what vintage let alone who the producer was. You were expected to trust the restaurateur.

Now we have almost come full circle, and most young restaurant managers are now confident enough to build their own lists. Those lists are shorter, they’re more eclectic, and they are designed with the restaurant’s food in mind. This has worked against the French. It’s hard to look clever putting another Côte du Rhône or Bordeaux Superior on your list. Yes, there are producers from the Jura to Muscadet who have made themselves look smart and trendy, but it is the big established regions with enforced uniformity that are struggling currently.

Why is Italy in particular having so much success in the UK on-trade?

Value for money is not unimportant. Many of the top French appellations are now so expensive that they no longer fit with what UK restaurateurs know they can sell a bottle of wine for. Also there would seem to be no place any more on restaurant wine lists in mature markets for “show off” wines. Above all, it is that Italian producers can put ‘wine that tastes like wine’ on a wine list at the right price, something some countries’ largest producers can’t currently be accused of. So, for the curious, and research confirms that emerging drinkers are more curious than ever, Italy kind of has it all.

The increase in the number of premium end Italian restaurants like Sartoria has helped distributors become more ambitious in their Italian ranges

What styles of wine are driving this shift towards Italy?

It is tempting to think that this must be all about Prosecco, Pinot Grigio and rosé. But it’s not. That was 10 years ago. All regions of Italy can be found on wine lists. In my view the biggest factor is the styles of wines themselves. They are what restaurants and their customer want. It’s all about the depth and sophistication of the Italian offer. There’s a real sense of discovery where the more ‘indigenous’ varieties are concerned.

Any other factors behind the appeal of Italian wine in the UK on-trade?

Ultimately, it is the styles of the wines that win. They are what restaurants and their customers want. Textural, interesting white wines with lower sulphur levels. Italian white wines have improved during the last five years. And savoury, elegant, medium-weight red wine has been a speciality for most Italian regions for many years. These have continued to improve at the same time as they have become better known.

Spain is the country that comes third in the UK on-trade listings – with 13% share up from 10% in 2018. What do you think is the enduring attraction of Spanish wine for British wine drinkers?

Many of the same things can be said about Spain’s wine offer as of Italy. Spain, for as long as we have been measuring it, has oscillated wildly in terms of it fashionability in the UK. This, however, has been Spain’s best year ever by some way and, they would surely hope, may represent the breaking of that cycle. Spain is also having the same sort of success as Italy in Canada, the US and, to a lesser extent, Australia.

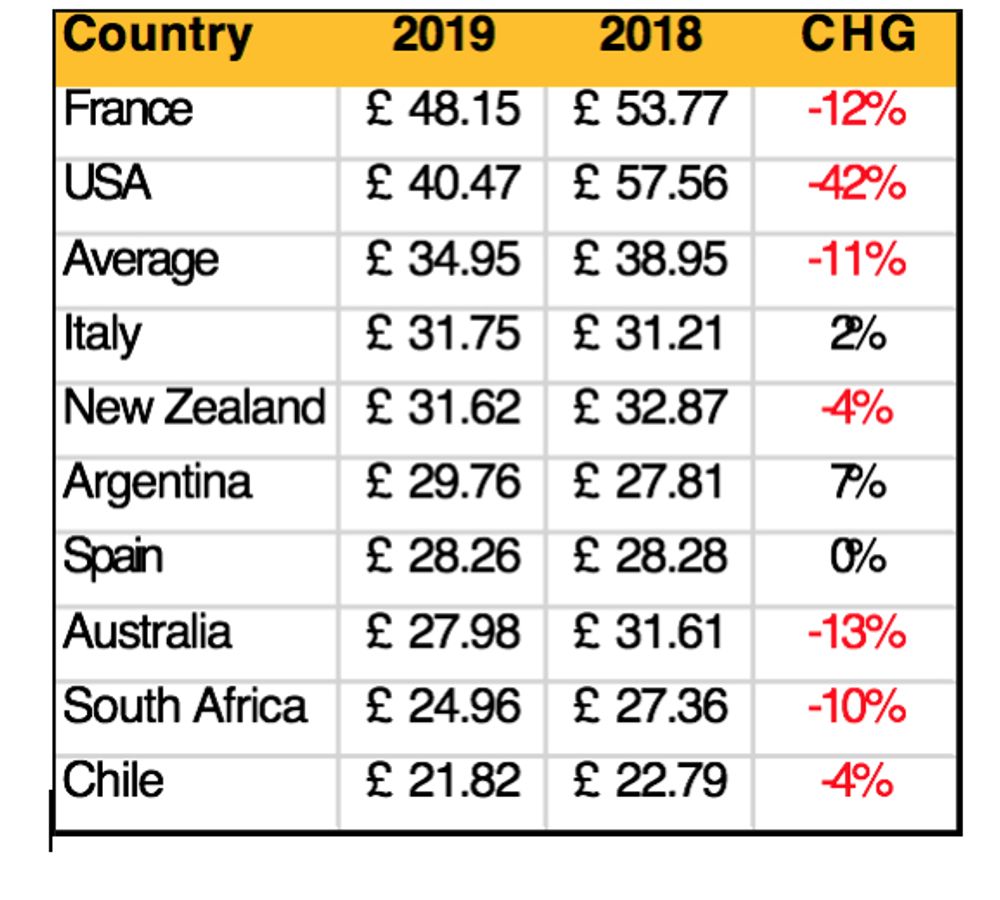

Average Listed Price of a Bottle of Wine on a UK Wine List in 2019 vs 2018

And what about the New Worldproducers? How have they been faring in the UK on-trade in recent times?

Chile and Australia have had a small reprieve in terms of their share of UK listings (both up 3% and now have 8% and 6% overall share respectively) as a result of people under financial pressure seeking out familiar supermarket brands. This, however, has driven the average price down for both countries putting them in a worse position. When the market recovers and returns to quality, they will be the worst affected. France will be first to bounce back, based on more than 10 years of measuring these markets.

Argentina, despite all of its internal political and economic woes, has successfully pushed prices higher, setting the country up well, in terms of maintaining image, as the focus moves away from Malbec and towards ‘Mediterranean Reds’ (Argentina has a 5% overall share of UK listings).

It’s been an issue for South Africa (down 17% in terms of their listings) that, whilst last year the spotlight was on them, Spain and Italy have very much taken that up this year.

New Zealand’s listings were also down (by 7%) mainly due to Sauvignon Blanc as a category losing out to Italian white varietals. Chardonnay fared much worse (down over 20%). US average prices are well down but there is still good demand at high prices for Napa and Sonoma Cabernet.

Naughty but nice…sharing food and platters are encouraging customers try a wider range of wines (Tayo Lee Nelson Photography)

How do you explain New Zealand’s drop in listings? Isn’t Kiwi Sauvignon Blanc the default white wine for many Brits?

I have been pressuring New Zealand for at least five years pointing out the way in which markets are evolving and just how much of a threat that poses. Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc has always been made as a style best for drinking by itself rather than enjoying with food (where 94% of all wine consumption takes place) and if the world on-premise wine trade decide en-masse that they don’t want overbearingly ripe fruit aromas drowning out their increasingly refined food then New Zealand is in all sorts.

So far, where white wine is concerned, Italy, Spain and Portugal have been taking share off everyone else, the host nation most of all (France being proxy host nation in the UK) and not off New Zealand (except in the UK). Maybe Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc is just too stylistically different to be troubled by Italian wines or maybe it is next.

I would maintain that Marlborough is only safe for as long as Sancerre decides not to price head to head. They may never do that. They may decide, as the French often do, to sell less wine at higher margins, to thereby protect their brand so as to put the foot down when the economy improves.It’s a strategy that works brilliantly for the leading Champagne brands. Whenever an economy is strong, we see Marlborough swapped out for Sancerre.

New French restaurants such as Frenchie are certainly doing their bit to bring a new image for French wine in relaxed fine dining environments

Which countries and styles do you think will rise to prominence in the coming year?

As far as suppliers are concerned, this is one of the frustrating things about the UK market. You already have the biggest and best wine selection on earth and yet you have major importers who are trying to make Brazil or Eastern Europe or wherever the ‘next big thing’, not because there is demand but because they are bored.

The only way anything gets to be ‘the next big thing’ is if it is both different and better. That is why Italy is winning. Whilst the appeal of the wines is their ancient heritage, they do what they do better than anything else does currently and that is the reason for the success.

There are wines styles like Georgia’s Saperavi, Hungarian Tokaji and wine brands like Lebanon’s Chateau Musar that have succeeded through being a ‘uniform for individuals’ who want to have something ‘a bit special’ for their customers. These wine styles do clear the hurdle of being different and better at their jobs than anything else. They have incredibly strong positions with their respective niches.

In order for an entire country to succeed in that way, as New Zealand has with Sauvignon Blanc and Argentina with Malbec, that requires universal quality. I’m not seeing that in many of the places that some UK importers are trying to hype into the next trend. Everyone would be better off, I believe, by diving deeper into the massive offer that is already at the table, as it were.

How do UK consumers differ from their Australasian, US or European counterparts in their wine preferences, it at all?

I was asked by an MW the other day about who is driving trends and which country starts them? My answer was everyone and no one. The global hospitality sector is connected via Instagram and ideas spread like wildfire.

There are, however, some differences. The biggest, from my perspective, is Riesling. Riesling makes up around 15% of white wine listings in all other markets that we measure. In the UK, it is only 3.5% and shrinking. It used to be possible to simple dismiss it as the legacy of Liebfraumilch. That was a generation ago. Just exactly why the current generation are not taking to it remains a mystery, to me at least.

There’s been a big drop in the average price of US wine being listed in the UK on-trade. How do you explain that?

The Texas Barbecue thing was the biggest trend in hospitality globally two to three years ago and many restaurants bravely ranged a bunch of high-priced US wines in support. When they didn’t sell and got delisted, the average price came down a lot. It has not been all bad for the US as now that people know Napa and Sonoma Cabernet, those wines have retained a good following.

Beefsteak Club Malbec has been a big hit in the casual dining sector

Meanwhile, Argentina’s average price has increased by 7%. What has driven that increase?

Given all of the political and economic turmoil in Argentina, price rises are probably the last thing that most people would be expecting. Digging deep into it, rather there being a collective effort to get prices up thereby improving brand image, it has really only been businesses like Vina Penaflor (Trapiche) and LVMH (Chandon) who are both growing their market share aggressively whilst raising prices at the same time.

What do you think is the future outlook for the UK on-trade sector?

I think the future of the UK market is incredibly bright. It remains one of the largest and most diverse markets on earth. It really is the true ‘litmus’ for brands.

Right now, it is so tough and profitless for suppliers that many are questioning why they are continuing. When Britain resumes it place in world once clear of Brexit, things will be very different. The economy will recover and so will the wine market. London especially will remain a global hub of wine and food culture and the real test of a brand.

- If you would like to buy the full report then follow this link.

- The report is based on wine lists taken at random from regular suburban restaurants, fine dining, hotels, pubs and upmarket bar venues. WBS says “we stratify the sample in proportion to the population excepting that we increase the weighting of Northern Ireland and Scotland slightly to improve accuracy when reviewing these markets in isolation. The split used is as follows: Midlands and East Anglia 19%; The South East 19%; North 17%; London 15%; Scotland 11%; The South West 8%; Wales 6%; Northern Ireland 5%.

- Other key findings show that the top 30 on-trade distributors in the UK in 2019 are responsible for 71.3% of all listings.

- Around 19% of wine is consumed in the on-trade in the UK. That’s almost 29m 9 litre cases. This is similar to the proportion in the US and Australia.