Justin Keay puts the renaissance of Moldovan wine into a socio-political context before picking out the six best wines at a Moldovan wine tasting.

Until Jack Whitehall visited it in the latest Netflix series of Travels with My Father, I’m willing to bet that most people in the UK had never heard of Moldova. Europe’s least known country is landlocked, dirt poor and, like so many places that border Russia, afflicted by an internal territorial dispute in which Moscow is directly involved – in Moldova’s case, the largely Russian-speaking breakaway region of Trans-Dniester, which contain the former Soviet republic’s industrial base.

As with Georgia, Ukraine and Azerbaijan, Moscow has ruthlessly taken advantage of ethnic tensions to undermine a neighbouring state’s integrity.

The Moldovan wine industry, nay the entire country, was put on the map overnight by one episode of Jack Whitehall’s Travels With My Father in which the pair have a wine tasting in Moldova.

Moldova’s case is a complex one, in which wine plays a key part

Years ago, when I worked as an in-house journalist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, I had responsibility for Moldova because I also covered Romania of which Moldova was part until 1945. It was hard to be upbeat, frankly, which is why many in Moldova still campaign for re-unification. And why not? The two share a common language and culture, of which a mutual love of wine is part; indeed the two share some common indigenous varieties, including Feteasca Alba and Feteasca Regala.

Wine is just a small part of Romania’s ongoing renaissance – this large country also has a large industrial base and a huge and fast growing IT industry with more unicorns than you can shake a fist at. For Moldova, however, wine is pretty much, well, everything. Under the autarkic Soviet system, Moldova was responsible for wine production and as an independent state this dependence has continued.

The Moldovan wine industry is vast, and still largely untapped in the UK market, something that could well change after further Brexit-linked devaluation of Sterling

Moldova has more vines per capita than anywhere else in the world – over 7% of arable land and 4% of total land – with wine accounting for anything up to one quarter of foreign currency earnings; historically, Russia has accounted for some 95% of wine exports.

Although Russia was an uncomplaining market, it was hardly an easy one, with embargoes imposed by Moscow in 2006 and 2013 over perceived quality failings. In reality these were because Chisinau (the Moldovan state capital) was minded to sign an Association Agreement with Brussels, which it duly did in 2014. Since independence in 1992 the powers that be have alternated between looking eastwards towards Moscow and westwards, towards Romania and the EU.

With exporters now desperate to find reliable alternative markets to Russia, Moldova has embarked on the complete overhaul of its wine sector. New producers have emerged in the countries’ three main wine regions, though not on the scale of Hungary or Romania, in part because Moldovan land restitution was less conducive to it.

Quality rather than quantity is now the driving factor, with producers seeking to make wines that will appeal to western palates rather than the one dimensional, sweetish wines that the typical Russian palate appreciates. Some €350m has now been invested, with more to come, with new technology, production equipment and new plantings introduced across the industry.

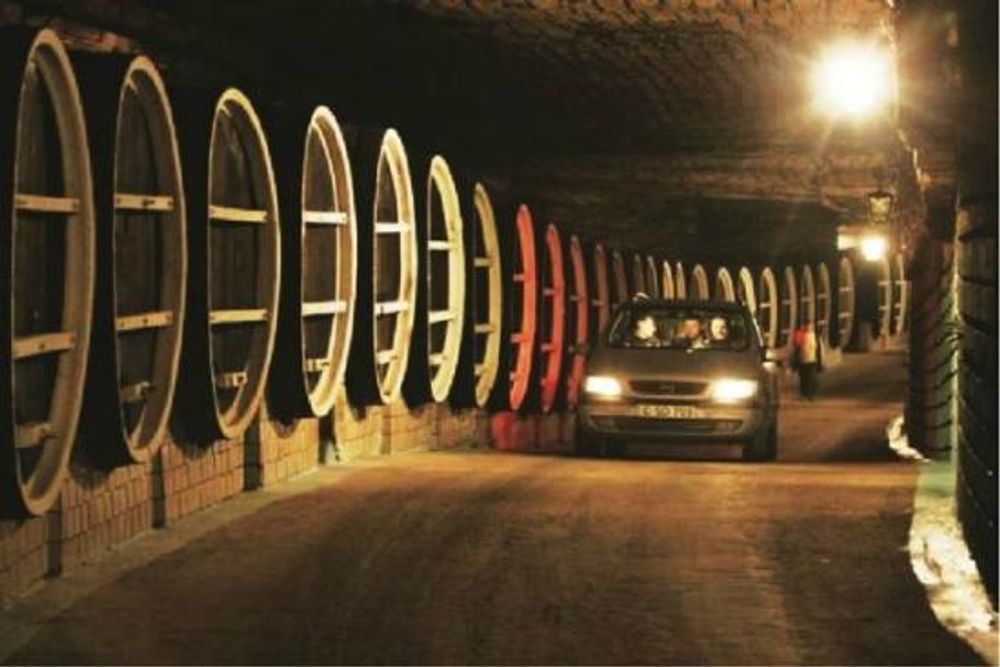

The wine cellars at Milestii Mici total 55km, making them the world’s largest

“Much of the wine Moldova exported to Russia before the first embargo in 2006 was foul, with pretty much every fault in the book,” says Caroline Gilby MW, author of a comprehensive new guide titled Wines of Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova (Infinite Ideas). She says quality has been on a fast upwards curb, though much is still in flux.

“With so much at stake, they really need to get it right,” she says.

Moldova has already had some success in targeting the non-Russian market, with sales to Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic all registering strong gains. The focus is now also on the UK, and last week Novus BH Magister, a Guildford-based importer specialising in Moldovan wine, hosted a tasting in London at which Gilby gave two masterclasses, focusing on indigenous and international varieties.

What emerged is that Moldova’s wine industry today is much like the country itself – in a fascinating though somewhat troubled state of transition, looking westwards but still burdened by the legacy of the past.

On the one hand, it is clearly moving away from the mass-produced stuff with quality much improved from the bad old days when, as one former importer said to me, “They just gave you the wine and expected you to like it”; there is value to be had pretty much across the board.

Yet, frustratingly, most producers have opted for international varieties (Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay are the three most planted) rather than experiment with local ones like Hungary and Georgia are doing, or even Romania and Bulgaria, where increasingly attention is also turning to native grapes. The worry is that Moldova may have to compete on price grounds for their market share, never a comfortable approach over the long term; far better to be able to offer some high quality Feteasca Alba or Feteasca Neagra or (another local variety I’d never heard of) Rara Neagra. And many of the reds in particular at the tasting were overdone, particularly some of the multi-blends I tasted, though it must be said, not lacking in ambition.

That said, some of the whites were a revelation particularly the wines made from Viorica, a Muscat-like native crossing only grown in Moldova; Cricova‘s Viorica 2017 and Timbrus‘ Viorica 2017 were both full-on good examples of this.

Moldova is also making good value whites from more traditional varieties: pretty much everything produced by Salcuta was fresh, fruit-forward and appealing, with the Pinot Gris, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay a great mid-level range that would do well here, particularly with a trade price of just £6.20 a bottle.

Good reds were harder to find, with many of the blends made from mainly international varieties tasting as if they could have been made anywhere.

That said, the presence at the tasting of supermarket buyers, and the need for the UK trade to find value after the almost inevitable further devaluation of Sterling post-Brexit, suggest we may soon be seeing more Moldovan wine in the UK. Though it is hard to make any predictions about after March 2019, one thing is certain: we will be getting a lot more Moldovan Lei to the Pound than Euros.

Six of the best wines from Moldova

Fautor, Aurore Rara Negro 2016

A rare outing for this local grape to appear in single varietal form; lightly oaked, good dark berry fruit on the nose and palate, very expressive. (£9.95 trade, ex-VAT).

Fautor, Negre 2016

A bigger, bolder version of the above but this time with just 30% Rara and 70% Feteasca Neagra. This is full-on – 14.5% – fruit-forward but with lots of freshness. Surprisingly complex. (£14.55, trade, ex-VAT).

Salcuta, Pinot Gris 2017

A delicious light expression of the grape, this would make a great aperitif but also a good food wine as well. Modern and well made. (£6.20 trade, ex-VAT).

Cricova, Viorica 2017

This was my favourite of the two Vioricas on show at the tasting, light but also rounded and quite intense, with restrained Muscat-like flavours. (£6.70 trade ex-VAT).

Salcuta, Tamaiosa de Salcuta Rose 2017

I almost passed this one by but am very glad I didn’t. A blend of 70% Pinot Noir and 30% Muscat de Hamburg (no, me neither) this is a deliciously balanced, fruit-driven pink wine made with hand-harvested grapes kept on fine yeast for 60 days. Very moreish. (£6.65 trade, ex-VAT)

Chateau Vartely, Feteasca Regala Riesling 2017

This winery specialises in blends – which include an unusual Rara Neagra, Malbec and Syrah – and this is one of the better ones. Quite straightforward, with expressive fruit, textured. (£9.20 trade, ex-VAT)