Attracting Italian investors into the region, increasing tourism and clarifying the marketing message are all major factors to increasing Pignoletto’s fortunes, argues Keay.

If anyone ever comes to write the definitive account of contemporary Italian wine, they should include a hefty section on former bulk wine regions that have overhauled their reputations.

Over the past decade Abruzzo, Le Marche and Molise – to name just three – have taken this route, with tired cooperatives making way for younger, more dynamic producers prepared to work with indigenous varieties, and to prioritise quality over quantity. Emilia-Romagna is following suit with local wine Consorzios keen to see local producers attain a quality level that will let the industry stand proudly alongside the region’s famous gastronomy, one of Italy’s most outstanding.

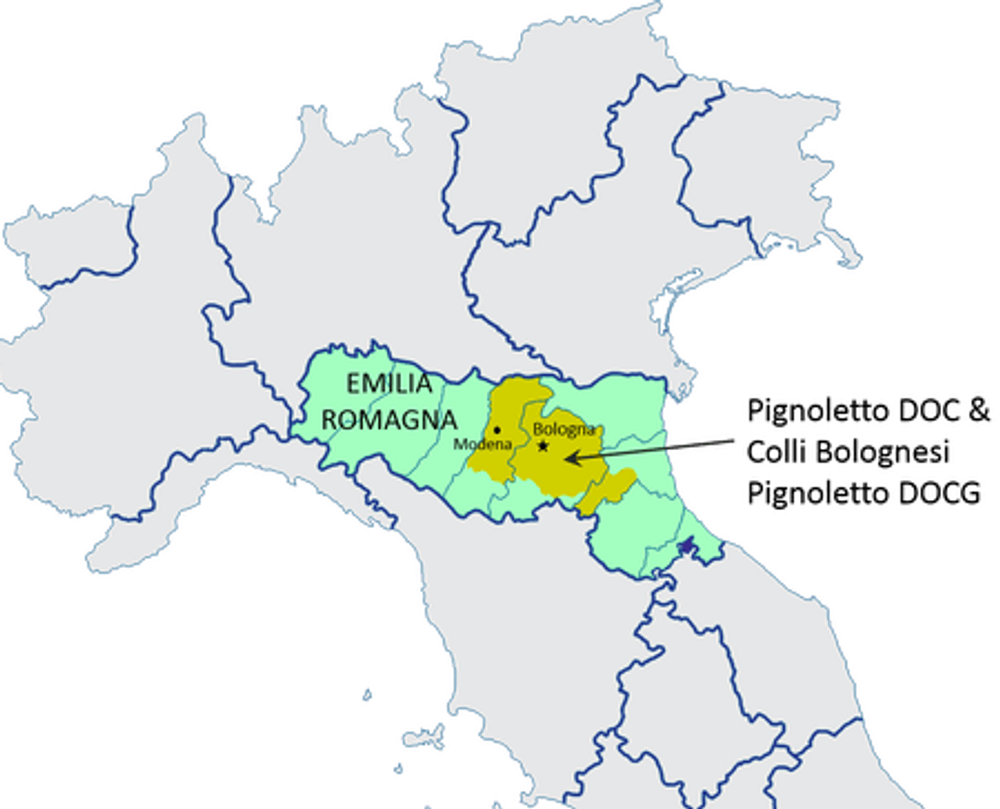

Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto DOCG was actually established back in 2010, the second DOCG to be set up in Emilia-Romagna, covering a hilly area between Bologna and Modena. It is focused, as its name suggests, on the area’s traditional sparkling wine, which comes in Spumante and Frizzante style, although Pignoletto is also made successfully here as a quality still wine (Superiore and Classico Superiore). And it has been on a big export push, with producers keen to find new markets abroad: currently just 10% of production is sold abroad.

Determining the quality of Pignoletto

Curious, I decided to judge for myself what strides Pignoletto has made towards quality in a DOCG where a well-regarded wine encylopaedia suggests, “few producers aim for quality as most Pignoletto ends up in the tanks of large bottlers and huge cooperatives.”

Although Pignoletto is actually grown in a much wider area – indeed, pretty much all the way across to Rimini, in the east and to the west, beyond Modena (home to another famous sparkling wine, Lambrusco) – Colli Bolognesi is home to the quality end of Pignoletto. In essence, the DOCG is to Pignoletto what Asolo and Conegliano-Valdobiaddene are to Prosecco. However the Consorzio – which this being Italy, works alongside another Consorzio (Consorzio Pignoletto Emilia Romagna) to promote the wine internationally – isn’t too keen on comparisons.

“Actually, we don’t wish to compete with Prosecco but maybe Pignoletto could become a good alternative. We don’t produce anywhere near the same amount so there couldn’t be (serious) competition. However Pignoletto has more complexity and better features and Grechetto Gentile can be used to make sparkling, still and even passito wines,” says the Consorzio’s director Giacomo Savorini, suggesting – as many here do – that the variety used to make the wine is superior to, and more nuanced than Glera, the Prosecco grape.

Pignoletto has been a big hit in the UK off trade, Daily Mail

For this reason perhaps (or because Brits have become conditioned to love sparkling wine that begins with P and ends with O) Pignoletto is doing well in the UK off-trade, most notably at Sainsbury’s – which sells an 11% ABV, Prosecco-like spumante usually at a discounted price around £6 – and Tesco, which sells a slightly higher end version with 11.5% ABV in its Finest range for around £8.50; both own-label wines are in fact made by the same large producer Cavicchioli, which also makes a range of Lambrusci.

Waitrose also sells an extra dry 11.5% spumante Vecchia Modena produced by Chiarli 1860, made to the west of the Colli Bolognese DOCG, for around £10 when not on discount, and the wine gets consistent high ratings.

Some in the industry say Pignoletto’s time has come. Steve Daniel of Hallgarten & Novum which sells a frizzante Pignoletto from Colli d’Imola – a moreish, well-priced fruit forward wine perfect for summer drinking – says sales are up 50% on last year. He reckons the outlook is similarly good, although he admits “nothing will ever be as big as Prosecco again.”

“Pignoletto is a fantastic drink; more mineral, complex and food-friendly than Prosecco and it provides far better value for money, as Glera grapes from DOC and DOCG area are so expensive,” Daniel argues.

Pignoletto also has the advantage that it is widely available in the frizzante style – popular in Italy because of its food-friendliness but relatively scarce in terms of the Proseccos imported here.

Some of the DOCG wines were particularly innovative with producers from higher elevations, like Nugareto, making sophisticated wines that really need food to bring out the best.

Yet for some importers, it just hasn’t taken off. At a recent Berkmann Italian tasting I was surprised to see that although lots of high quality Prosecco and Franciacorta were in evidence, Pignoletto was quite absent.

“You know what? We never seriously thought about it – maybe because the supermarkets are offering such great Pignoletto already,” says head buyer Alex Hunt.

Berry Bros & Rudd? The same story. Likewise Armit and Winetraders, the Oxford-based single estate Italian specialist run by Michael Palij; they offer a great Lambrusco made by Vittorio Graziano outside Modena but again, no Pignoletto. Winchester-based Stone Vine & Sun used to offer a great Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto – Floriano Cinti – which for me really stood out at the importer’s Christmas tasting. Yet it hasn’t done well, and owner Simon Taylor says he has been obliged to stop importing it. “The wine was brilliant but only a few people liked it (and they liked it a lot) I don’t think we ever sold more than a dozen to any single person. And no on-trade either. Prosecco still rules,” he says.

So what’s the problem with Pignoletto?

Quality isn’t a concern, as a tasting of 55 sparkling, frizzante and still wines organised by the Consorzio confirmed. Quite a few of the Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto DOCG wines in particular stood out, with Tenuta Santa Croce, Montevecchio Isolani (a historic producer coincidentally owned by the Consorzio president Francesco Cavazza) and Fattorie Vallona scoring very highly for quality and accessibility; incidentally the latter also makes an impressive range of still wines notably using Cabernet Sauvignon but also some of the region’s largely forgotten native grapes like Negretto and Vigna del Fantini.

Attracting big name Italian investors into the region is one of the key challenges

An absence of big producers is likewise not a problem: although there has been some movement, Pignoletto is still dominated by large families, coops and former coops, who bring economies of scale, without forsaking quality, to their wines. Cavicchioli, for example, produces over 10 million bottles yet retains a strong quality profile.

But a lack of internationally known names – notably those active in other more highly regarded wine regions in Italy who could show the way forward for Pignoletto – is clearly an issue. Coupled with the failure of excellent local producers like Vallona and Monteveccio to become better known outside Emilia-Romagna, it might be one reason Pignoletto hasn’t made more inroads into the on-trade.

“Actually it is the biggest problem: our aim in coming years is to add value to our soil to make the entire region more attractive for big Italian investors and producers,” says Giacomo Savorini.

Another priority should be to clarify the marketing message, which has if anything been muddied by recent changes.

Pignoletto used to be made from the Pignoletto grape, but no longer – in an effort to preserve the name for the product, the variety has been renamed Grechetto Gentile (not the same variety as Umbria’s Grechetto) but is also known locally variously as Grechetto di Todi and Alionzina. In an effort to provide some sort of origin backstory, a tiny local village in the heart of Colli Bolognesi is now called Pignoletto. All this though is rather confusing for consumers who just want a good drop of sparkling wine.

Give me a Pignoletto over a Prosecco any day

For Steve Daniel, time may play to Pignoletto’s advantage.

“Pignoletto can certainly gain a larger foothold in the UK if Bologna takes off as a tourist destination and this drives its local produce. There is no reason it shouldn’t – it is the gastronomic stomach of Italy and the cuisine is world-renowned. Pignoletto, alongside Lambrusco, are the local wines which go very well with the local food,” he says, adding:

“Give me a Pignoletto over a Prosecco any day.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Over the three days I tasted my way through the Colli Bolognesi, I came to realise just how nuanced Pignoletto can be, with some of the smaller producers (up to 100,000 bottles a year) some of the most ambitious in terms of pushing the quality and stylistic envelope. Some of the DOCG wines were particularly innovative with producers from higher elevations, like Nugareto, making sophisticated wines that really need food to bring out the best; by contrast Tenuta La Riva makes a weighty Pignoletto that has spent 42 months, that’s right three and a half years, on the lees.

Federico Orsi opens his organic natural wines

Meanwhile some producers like Orsi – Vigneto San Vito have unashamedly gone the natural wine route making sometimes cloudy, often challenging wines that would be snapped up in Hoxton Square or other hipster joints in an instant, but which are genuinely appealing even to us squarer, more mature folk who occasionally yearn for something different.

Indeed even the more bog standard Pignoletti – mainly those from the Pignoletto DOC rather than the Colli Bolognesi DOCG – have a freshness and character to them that mainstream Prosecco from say the Treviso region completely lack, with the broad fruit flavour profile of Grechetto Gentile tending to produce a far more satisfactory wine. And then there are the still wines, many of which spend time in barrique and thus show a completely different side to Pignoletto.

All of which suggests that Pignoletto’s curiously low profile in the UK on-trade won’t last for long. With some much innovation taking place, especially within the Colli Bolognese DOCG, it seems clear that Pignoletto’s best days are yet to come.