“The Gorbachev crackdown on alcohol in the 1990s prompted the need to discover other markets and, given the fact that Turkey was never likely to be a major importer, the line of vision had to be set further west, and, as it turned out, further east too,” writes Field.

Azerbaijan, anyone? In the news recently, wasn’t it? But where is it? Hmmm; somewhere east of Istanbul and west of all those countries ending in ‘Stan, maybe? Indeed; add mention of the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea and you are just about there. The three countries of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan map out a mountainous bulwark between Asia Minor and the greater European landmass now (still) dominated by Russia.

The over-rehearsed maxim about the ‘cradle of civilization’ is well deserved, however. For over seventeen centuries this has been the multi-cultural melting pot where East meets West, its anthropological significance writ large as a key staging post on the ancient Silk Road. Visiting the Azeri town of Sheki is an almost surreal experience; it is said to resemble Florence in the time of the Medicis!

Fire is a constant leitmotif in Azerbaijan

Cultural and commercial cross fertilisation is always challenging, yet also incredibly inspiring, more often than not. The culture of wine is no exception, nor should it be, as vines have been here from the very beginning…. let’s not forget that Noah planted a vineyard in Armenia, enjoying its fruits somewhat liberally before the rains set in.

Let us step back briefly from intimations of the ancient qvevri culture……’Azer’ in Persian means ‘fire’ and fire is a constant leitmotif in Azerbaijan. It was in the Caucasus, after all, where Zeus chained Prometheus to a rock for stealing the fire of the Gods. By coincidence, or maybe not, it is the extraordinary natural gas resources which lie beneath this fertile land which have fed an economic renaissance, and which underwrite, literally in this case, a very distinctive terroir for the grapes. One of Azerbaijan’s most popular tourist destinations, indeed, is the eternal underground flame burning bright in Yanar Dag. Eat your heart out, Olympic flame!

East meets West in the capital Baku

Gratitude at nature’s benevolence is captured by architectural extravagance, with some of the key modern buildings in Baku, the capital city, influenced by the shape of a flame. Who needs London’s Walkie Talkie or Cheesegrater, somewhat prosaic in comparison, when one can have Zaha Hadid’s eternal flame of a legacy, Heydar Aliyev, in Baku? Who indeed? All around one can witness Post-Soviet prosperity and a diversity, as hinted above, that has been bred in the bone.

On the subject of diversity, and heading off-piste for a moment, Azerbaijan is also the centre of the World’s Arm-wrestling Federation and what is more boasts per capita (population 10 million) more chess Grand Masters than any other country in the world. If you fancy a game of chess in downtown Baku, therefore, and, starting to lose, feel sufficiently aggrieved to start a fight, there is a good chance that you will lose twice over!

Azerbaijan fell under the Soviet yoke in 1920, eventually extracting itself with several others and declaring independence in 1991. It may be described as a unitary semi-Presidential Republic, and the extant dynasty, with IIham Aliyev at its head, is far from pusillanimous. It must be that strength thing again, strength and fire. The population is 95% Muslim, its Zoroastrian heritage somewhat in a minority these days, and its closest ally Turkey rather than Russia.

The recent military ‘success’ in the enclave of Nagorno Karabakh, long claimed by Armenian separatists, sheds an interesting light on the geopolitics of the Caucasus. Armenia was backed by Russia. The Karabakh stallion, we note, remains the emblem of Azerbaijan. An elegant but very solid beast, of that we can be assured.

But what of the wine?

The altitude, volcanic soils and proximity to the Caspian Sea all influence the style of Azeri wines

Production is approximately ten times larger than the UK, but ten times smaller than Georgia; it sits at about No 50 in the league table and, leaving aside a history of bulk shipments, produces the equivalent of 60-80 million bottles a year. Not that much. Indeed, touching briefly on the geopolitics again, most of the 50% of export was historically sent over to Russia, and was generally of a poor standard.

The Gorbachev crackdown on alcohol in the 1990s prompted the need to discover other markets and, given the fact that Turkey was never likely to be a major importer, the line of vision had to be set further west, and, as it turned out, further east too. Quality had to be addressed and a marketing strategy initiated; both proceed apace, with the majority of quality production now controlled by a handful of wineries and the latest export drive expertly curated by the Azerbaijan Tourist Board (ATB).

A propos, it is thanks to the ATB that the UK, a key target market, recently experienced a fascinating Zoom presentation, courtesy The Rebecca Lamont Wine School. Forty or so lucky Zoomers were sent, via the Azerbaijan London Embassy, three bottles each from the Chabiant Winery and were then treated to a masterclass from its winemaker, the Italian Andrea Uliva, who described the wines, and the cultural historian Giulio Vinaccia, who weaved in a backdrop every bit as elegant and inspiring as one of the famous Azeri carpets. The talk was of a lost continent, of a rich heritage, and of a vinous revival. And so much more.

The Chabiant Winery covers 250 hectares and is located in the municipality of Ismayilli, which has been compared to the Kakheti region of Georgia, and is well known, apart from its vinous pedigree, for a village called Ivanovka, run entirely and wonderfully anachronistically as an old school Soviet-style collective farm. Ismayilli is located close to the Goychany River Basin which cleaves its way between the Greater and Lesser Caucasus. A valley maybe, but it should always be borne in mind that the vineyards climb to 800 metres of altitude.

It is this altitude, allied to the relative proximity (this is a small country) of the Caspian Sea which explains the key diurnal variants which inform the style of the wines. That and the soil, which we have already touched upon. Apart from the gaseous and volcanic influences, there are significant limestone and calcium deposits in the soil, Andrea tells us. That’s a relief.

Will the future lie in indigenous varieties like Madrasa?

Equally fundamental is the choice of varietals. Might it be commercially ‘easier’ to gain a foothold in international markets by majoring in international grapes? It might be, and some distinguished Azeri wineries such as Savalan ASPI, certainly plough that furrow.

Andrea Uliva is adamant, however, that the future lies in a demonstration of quality of the indigenous varietals, by which he means those indigenous (and very widely planted) to the greater Caucasus (such as Saperavi and Rkatsiteli) but even more importantly those which are indigenous to Azerbaijan itself, specifically the white Bayan Shira and the rather curiously named red grape, Madrasa. Andrea, somewhat ironically, shows off his flamboyant Italian side when he maintains that he does not wish for any of his wines to taste remotely Italian. He is right, they don’t.

What do the wines taste of then, and how are they made?

Well, slightly paradoxically, whilst there are moves afoot here to promote these indigenous varietals, there is little by way of adherence to the traditional qvervi/amphorae winemaking methodology. This is not shunned, however, there are several experimental amphorae bottlings, but it is not put centre stage, either commercially or technically speaking. Maybe it is more widely practised in other wineries (almost certainly more so in Georgia and Armenia) and maybe it will come, but while Uliva extols the virtues of traditional winemaking and is fascinated by orange wines, the fact remains that the vast majority of the Chabiant production involves stainless steel, and to a greater or lesser extent, French oak, albeit never new.

The wines thereby are both reassuringly familiar and enticingly different.

To me the Bayan Shira has something of the Orvieto about it (best not tell Uliva); flowers, almonds, citric texture and a compelling freshness on the finish, its texture having been nourished by extensive bâtonnage. The red Madrasa is fascinating; black cherry, sloe, bilberry and spice; something recalls Grenache here (or might that be Cannonau) its elevage (70% stainless and 30% third-fill barrique) very familiar to the ‘western’ palate, but with teasing structural points of difference nurturing intrigue and prompting further enquiry.

The second red wine is less esoteric; it is a blend of 70% Saperavi (the ‘king’ red grape of the broader Caucasus region, pace Uliva) and 30% Cabernet Sauvignon. Rather amusingly, given the stature of the grape in question, Andrea confesses that he only uses Cabernet Sauvignon when it ‘plays second fiddle’ to its partner. Sure enough the wine has enticing clove/spice/wild strawberry interplay which does not seem especially Cabernet, and this is no bad thing.

20% of stems had been kept in the vat for this one and the wood ageing had been upped to 50%, over half of which is second fill. Relatively young (both reds 2017, the white 2018) the Saperavi blend has generous colour, a persuasive phenolic sub-plot and plenty of individuality. It was my particular favourite, but when Rebecca Lamont canvasses the audience each wine gains a third of the vote, an outcome with which Uliva appears far from displeased.

Andrea Uliva, winemaker at Chabiant

So, in conclusion…

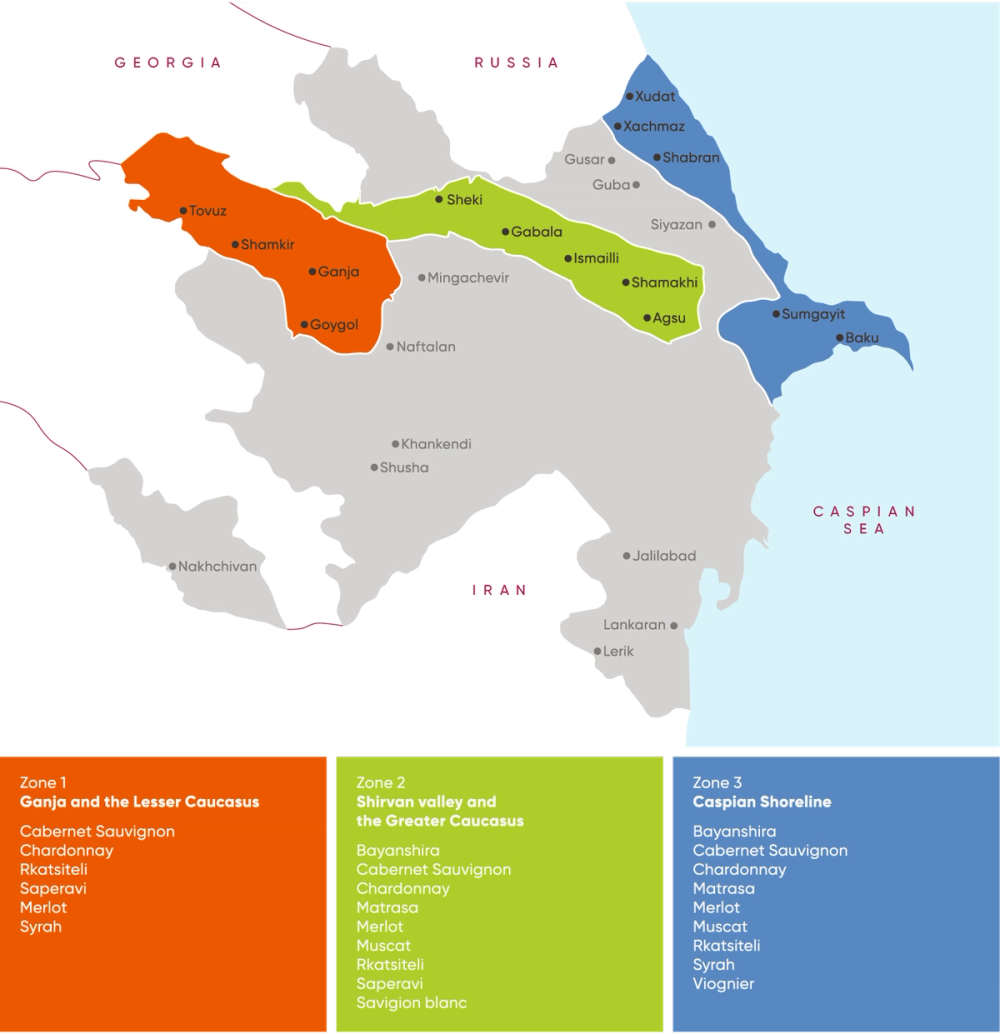

A fascinating experience. The next step will involve a spot of taxonomy; avoidance of the complications of the European model (AOC and DOC etc.) will probably lead to a system of classification which more closely approximates the American AVA model. Thus far three fundamental zones have been identified, with the key and historic Shirvan in the centre (Chabiant is located here), a second zone closer to Baku and the Caspian Sea in the east and finally, further west, an inland zone centred on the town of Ganja (another unfortunate name.) All three are located in the northern half of the country, closer to Russia than to Iran, and essentially following the rift valley between the upper and lower Caucuses.

An exciting discovery then: the rich seams of the cultural and historical backdrop provide an eloquent story upon which the established wineries such as Chabiant can build an international reputation. There is money for investment, a solid centralised marketing mechanic and an impressive spirit of self-confidence, careless, it seems, of any lingering broader geopolitical concerns. Markets are starting to open in Japan and China, also the USA; Russia is less significant these days, but still present, and there is activity in Poland and the Baltic States. The next stop is London.

The wines of Chabiant are currently unavailable in the UK but The Buyer will update readers as and when they are.