Petit Chablis is not ‘lesser Chablis’ and other myths debunked in the company of Raveneau, Fèvre, Defaix, Brocard, Moreau, Billaud and Droin.

Ask someone from Chablis what the difference is between the four appellations and you’re likely to get this answer.

“Petit Chablis is for drinking with strangers, Chablis you open when friends come round, Premier Cru is for when you have family and Grand Cru is for you to share with just your partner… or when they have gone to bed.”

On a technical level it is, of course, way more complicated than this but, as with all things in Chablis, there is a purity and a simplicity about that answer that is in keeping with this sleepy, iconic and rather gorgeous town.

Old barrels in the cellars of Raveneau – used mainly for show

Chablis is all about purity and simplicity after all – one region, one grape and, by and large, some general rules on vinification that do not differ nearly as much between winemakers as other, more diverse, wine regions.

Differences do come from winemaking styles – degrees of oak used mainly with Grand Cru – but by and large the main distinctions begin and end in the vineyard; the differences in Chablis are all about soil and slope.

If you ever needed one, Chablis is the almost perfect manifestation, and proof, of terroir itself.

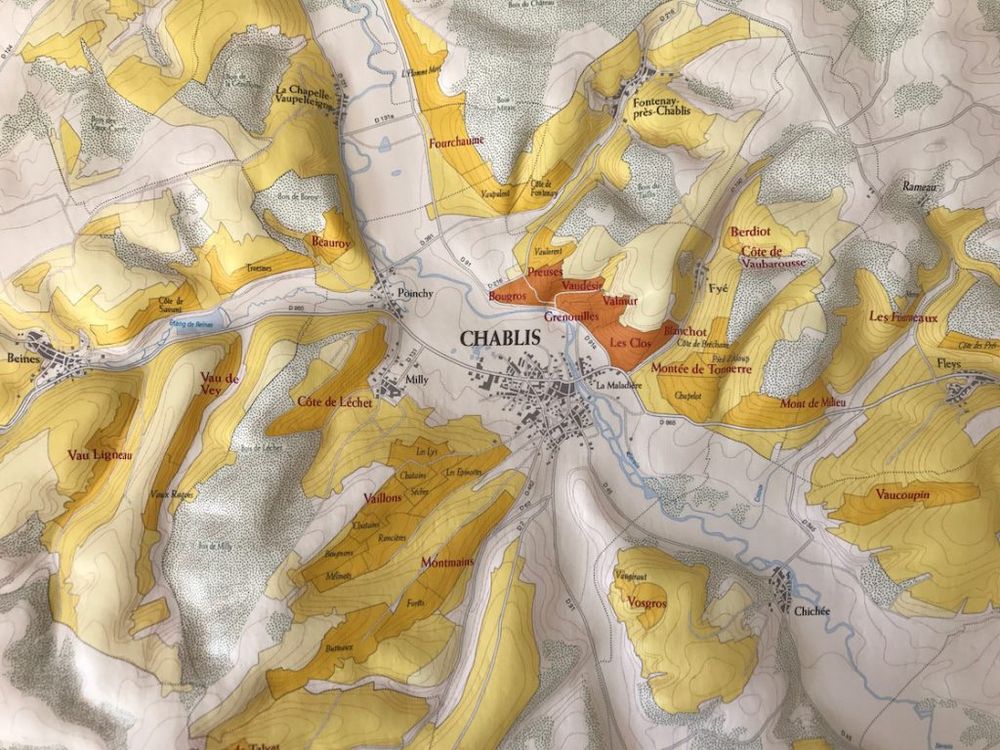

Understanding Chablis is all about understanding the topography of the region

The appellations all start with the type of soil and the location – principally the aspect and the slope. The steeper and more South-facing the slope the riper and higher quality the grapes will be.

This is, after all, a chilly part of France that we are talking about, that has harsh winters, can too often see frost in April and hail at all times. To give you an idea of how harsh the weather can be – between 1950 and 1960 Chablis had just three harvests, and one side of the most premium Grand Cru slope was a ski run. Recently too bad weather has dealt Chablis a rough hand.

Understanding Chablis is all about understanding the topography. The darkest areas are the Grand Cru sites, then Premier Cru, Chablis and Petit Chablis on the top of the hills.

So the aspect of the Grand Cru sites are South-West facing slopes and, with a few exceptions, the Premier Cru sites are mainly South-East facing.

Unlike the rest of Burgundy, of which Chablis is the most Northerly part, Chablis has four appellations and not three. They used to have three until 1944 when Petit Chablis was created to account for the newer vines being planted on top of the hills that are on more recent Portlandian limestone soil.

My guide Eric Szablowski with the most perfect means of transport, October 2016

My guide Eric Szablowski from the Chablis Commission of the Bourgogne Wine Board says “The difference between Premier Cru and Grand Cru is the place. The difference between Chablis and Petit Chablis is the quality of the soil and how much sun the vines get.”

Contrary to popular opinion Petit Chablis it not ‘lesser Chablis’ or second rate Chablis, it is fresher, lighter, less complex for easy drinking. On some instances, with some foods and from some producers (Samuel Billaud for example) there are examples of Petit Chablis I would choose over Chablis.

Quality of soil is a key differentiator. Where Petit Chablis comes from recent Portlandian limestone, Chablis and Premier Cru has limestone soil formed in the upper Jurassic era, or Kimmeridgian.

This is soil with lots of fossilised oyster shells, hence the proliferation of fossil designs on many Chablis producers’ wine labels.

Where the slopes are steepest – the Grand Cru sites – the Kimmeridgian soil shows on the surface.

Chablis is the main wine of the area, accounting for 66% of overall production compared to the Grand Crus’ 1-2%, Premier Crus’ 14% and Petit Chablis’ 18%.

Chablis differs from Petit Chablis in its greater complexity, volume in the mouth, structure and persistence. On top of the customary notes of white flowers, gunflint and citrus, you can get notes of mint, sous-bois, liquorice and hay. Chablis in a nutshell simply has more depth and flavour than Petit Chablis.

Petit Chablis and Chablis both tend to be fermented in steel tank and never see any wood. Chablis Premier Cru can see some wood almost always after fermentation in steel tank and Chablis Grand Cru sees the most wood, usually a blend of oaked and non-oaked components.

With some examples of Chablis you can clearly taste the minerals and stone in the wine.

So, although the key distinctions for the appellations come from the specific site of the vineyard, this determines the quality of the grapes and what can be done with them afterwards – whether they are able to withstand more structure from the wood and more ageing.

Historically, Chablis was always meant to be drunk after about six years ageing and was often referred to as a golden wine. Today’s economics dictate otherwise, of course, and you often get a greenish tinge to the wine.

What does seem totally wrong in my book is drinking Grand Cru Chablis (like any Grand Cru) before its drinking window.

But this is only half the story

As with all drawn lines and classifications there are many exceptions to the rules and a blurring of lines that makes for fascinating research and drinking.

The demarcation of the appellations sometimes feels arbitrary. On the left is Premier Cru site Vaulorent (which tastes like a Grand Cru in a blind tasting) and on the right is Grand Cru site Preuses.

With 47 climats in Chablis – 40 Premier Cru sites and seven Grand Cru sites – I am not going to unpick every area but Montée de Tonnerre and Vaulorent, for example, are Premier Cru sites that can ‘punch above their weight’ and reach Grand Cru standard in a blind tasting, primarily down to their location being either side of the Grand Cru sites.

Similarly, there are sites that are arguably delivering greater value-for-money. The most Westerly Grand Cru site Bougros, much favoured by William Fevre is more keenly priced than Les Clos that tends to be the most expensive.

So what do the winemakers think the differences are between Premier Cru and Grand Cru?

Didier Séguier, William Fèvre

Didier Séguier, winemaker at William Fèvre says “With Grand Cru you have more richness, better maturity, better energy, better balance and complexity. Premier Cru is more an expression of a particular area such as Montée de Tonnerre, which is very distinctive. Having said that Vaulorent can be like a Grand Cru in a blind tasting.”

Samuel Billaud

Samuel Billaud, whose new winery has recently been established after a messy ten year legal battle, agrees with Séguier.

“Grand Crus are more complex and ‘large’. There is a greater density of minerality, it has a more openly tense quality and there is a greater clarity to the wine. But having said that my great, great grandfather had land in Les Clos and Montée de Tonnerre which is a top Premier Cru and the quality is the same, it is a matter of taste. Montée de Tonnerre and Vaulorent are very close to being a Grand Cru.”

Julien Brocard, winemaker at Jean-Marc Brocard, one of the pioneers of the region. And yes, that is a real fossil.

Julien Brocard who is now taking over the reins of the winery Jean-Marc Brocard from his father, one of the main pioneers of Chablis, says the distinction between Premier Cru and Grand Cru can also be complicated by vine age, and not just from the soil and aspect.

“Usually we see more deepness in Grand Cru wines and many times more ageing potential and complexity but that’s not always true. You can also see this with old vines that are not Grand Cru. It depends upon the age of the vines but they can age better over a 30 year period. There can be no difference and there can be a big difference – Premier Cru and Grand Cru are human categories after all.”

Christian (l) and Fabien Moreau

Christian Moreau, of Domaine Christian Moreau Père & Fils has a greater percentage of Grand Cru to overall output than any other producer in the region thanks to his father and grandfather’s land acquisition. One distinction he makes is that with Grand Cru you tend to get 0.3-0.5% more alcohol “Because of its exposure you get a greater maturation of the grape, so we tend to pick these first, starting with Les Clos.”

Benoit Droin favours prodigious use of oak with his style of winemaking

Benoit Droin, winemaker at Domaine Jean-Paul & Benoit Droin believes that there are easier distinctions to be made in Chablis than between Premier and Grand Cru.

“It is easier to distinguish the difference between Chablis and Premier Cru, than Premier Cru and Grand Cru when they’re young. With Grand Cru you tend to get more concentration, richness, elegance, finesse, complexity and ageing potential. They also improve with age.”

“Grand Cru tends to be grown on different soil, it is more compact. Why these sites became Grand Cru I don’t know exactly but historically people knew the soil was richer and the wines would be better for ageing.”

“A sommelier has to let customers have what they prefer, but for the first five years Grand Cru is less expressive than Premier Cru and more expensive, so Grand Cru within that time is not a good choice.”

Hélène Defaix preparing the tasting

Hélène Defaix of Domaine Bernard Defaix elaborates “Grand Cru – it’s a bit more of everything, a bit more concentration, a bit more length or on the nose. Cost is not the reflection of quality it is very subjective. Sometimes it can be very expensive and sometimes not so expensive.”

Defaix believes, however, that the producer can often be more important than the appellation.

“It is true everywhere in Burgundy that there are so many producers and appellations. First I focus on the producer before the appellation. If you like their style then you can be more confident in the rest of their range..”

This is also a view shared by Isabelle Raveneau of the iconic producer Domaine Raveneau.

Isabelle Raveneau: choose the producer first, appellation second

“I would recommend that people look first at the producer they like and then the appellation and not the appellation first”

Tasting the Raveneau range from their barrel is a pinch-yourself moment for any wine lover of course. When you are tasting one appellation after the other the differences between the wines are blindingly obvious in their fruit expression, phenolics, balance, acidity, texture, structure, mouthfeel, tension and so on.

“The secret is that there is no secret. It starts in the vineyard and then it’s just hard work – producing the best quality grapes that you can have and being attentive to what you do. Winemaking is not that important if you have good products.”