If you want to get on top of your Chilean wine range and reflect the big changes taking place in the country then you need to have Itata as part of your range, says Amanda Barnes, journalist and author of the South America Wine Guide. Her are her five reasons for doing so.

1 Old vines aplenty, and then some

La Leona Pais planted in 1792 (left) and El Quillay Pais planted in 1867 (right) from Los Vinateros Bravos

There aren’t many wines you can taste that come from 223-year-old vines. Leo Erazo’s Granitico País comes from a plot of old bush vines planted in 1789 that remain ungrafted and in their original, gnarly glory in the hills of Itata’s Guarilihue village. You can buy it from Les Caves de Pyrene for just over £15. Or if that’s out of stock, you can find his A los Viñateros Bravos Resistencia País from vines planted in 1867. Or you could try Viña Prado’s País from ungrafted vines planted in 1870. And it’s not just País vines that are over a century old, there are vines of Cinsault, Semillon, Moscatel, Malbec and even Chassellas in Itata.

Itata is a true heartland of old vines and traditional farming techniques, where the 4,900+ vineyards are often ploughed by horses, every grape is hand-picked and the plots are measured by the number of vines rather than by hectares. Chile’s old vine register, including those of Itata, will make most wine region’s eyes water with many old vines well over 100 years old and some thriving into their second century.

2 A unique terroir

Of course old vines only continue to exist because they were always making good wine and part of the secret to Itata’s longevity is within its soils and climate. Itata was, in fact, one of the first major wine regions of Chile, planted in the mid-16th century when the Spanish first arrived and set up the port of Concepción, which became Chile’s capital at the time. Vineyards proliferated to the north (Maule), east (Itata) and south (Bio Bio) founding what is collectively Chile’s Secano Interior and remains a driving force in Chilean wine production today.

What makes Itata special is that is it set between rolling coastal hillsides at a southerly latitude. And while most of Chile’s vineyard topography is rather flat, Itata’s is crammed with undulating hills and steep valleys, making each village and vineyard quite distinctive. That is what is driving winemakers today to study the microclimates and micro sites of Itata, and begin identifying its top crus.

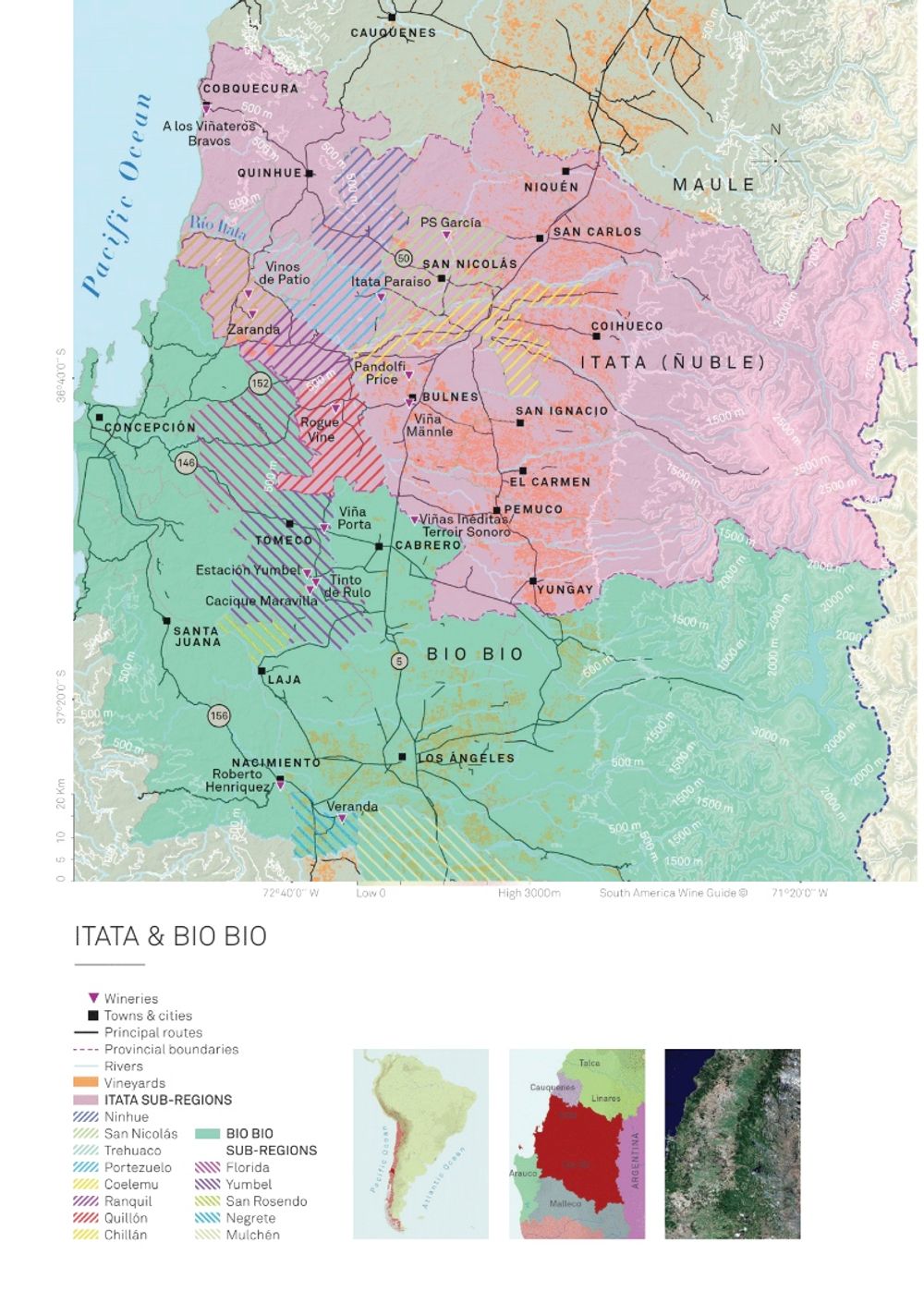

Itata and Bio Bio in a map from Amanda Barnes’ South America Wine Guide

Perhaps the most excitement is happening in the far west, where the coastal mountain range is rich in weathered granite and vines are often planted right into the bed rock with little, if any, top soil.

“The granite in Itata is very special because it has a lot of silt, which emulates limestone in the palate — giving the wines this elegant minerality, a good mid-palate and a very long finish,” explains one of the world’s foremost terroir experts, Pedro Parra, who also makes his own label of País and Cinsault wines in Itata. Further inland are river terraces with gravels and pockets of volcanic sand, which also add a different dimension to the wines. But they all share Itata’s mild climate where freshness is key and the expression is earthy and floral.

3 Sustainable farming

With 850 to 1,100 mm of rain each year, Itata is one of the few wine regions in the New World which needs no irrigation and can be completely dry farmed. Not only does that give it a promising future in Chile, where water resources are increasingly scarce, but it gives the wines extra kudos for sustainability. Add to that that these vineyards are usually managed organically, ploughed by horse and picked by hand, and that they secure the livelihoods of over 4,000 families who own and run them.

Artisanal winemaking is common in the region like here at Viña Prado

“Drinking [these wines] is a social topic, because [the vines] live with the local people in the countryside of Itata and Bio Bio— so it is a social issue,” says winemaker Roberto Henríquez, who makes artisanal wines from both Itata and neighbouring Bio Bio, including from 200-year-old País vines. “Protecting these ancient vines is a key part of protecting our local culture.”

Innovating local, artisanal traditions

Making wines in qvevri or amphorae might sound like a new fad for wine regions beyond Georgia or Greece, but actually in Itata producers have been making their wines in tinajas (their own ceramic vessels) for over 300 years — since close to the beginning of their winemaking history. It’s a tradition that has never died in Itata and you’ll see many of these old tinajas being used in the homes and artisanal wineries of producers throughout the region. It isn’t only clay though that is a common vessel for Itata’s wines, but also raulí wood barrels. A native beech tree, raulí has been used as a wine vessel in Itata since the late 16th century and several of the new generation of winemakers in Itata are restoring old family foudres made of raulí to reinstate this tradition and give a uniquely Chilean character to their wines.

Lomas de Llahuén making Pipeño wine in the traditional tinajas – the Chilean equivalent of a Georgian qvevri – that are common throughout Itata

Another of the artisanal techniques that is coming to the fore again is the use of the traditional zaranda cane mat as a destemmer. It offers a gentle way to de-stem, uses no electricity and employs local artisans to weave them. Small producers are bringing zarandas back, but so are medium producers like Bouchon and large producers like Torres, who both make wines in Itata. Although many of these traditions never really died, it’s the new generation that are bringing them into the limelight again.

Interesting wines

Itata’s wines are interesting. I mean ‘interesting’ not in the polite journalist way, but in a genuinely, make-you-think and spark your interest way. They naturally tap into the lower alcohol trend as well as the lighter, juicier and fresher styles we are all seeking, but they are also thought-provoking, engaging wines.

They are undisputedly great too. It was an Itata wine, Torres’ La Causa Cinsault-País-Carignan blend that took home a Best in Show medal at Decanter World Wine Awards this year, and De Martino’s orange Muscat aged in tinaja has never been shy of awards either.

I’m excited not only about País and Moscatel — the true champions of Chile’s old vines and historical wine regions — but also about the old vine Semillon which can be waxy and complex yet bracingly fresh, and the old-vine Cinsault which hovers over floral, earthy and mineral nuances within Itata’s top crus. There’s old vine Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon and Carignan which vie for some of the oldest ungrafted plantings in the world, but also new vines of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Syrah which also demand attention.

Itata is a huge part of Chile’s history, but I believe it is also paving the path for Chile’s future. And with the influx of young winemakers and the outpour of interesting wines in the past few years, I’m sure Itata will be the region on everyone’s lips in no time.

- Amanda Barnes is author of the recently published The South America Wine Guide and has been hosting a series of masterclasses for Itata producers planning to export to the UK this month. On October 7 in London at the Chilean Embassy she is hosting a tasting for importers and buyers with some small, artisanal producers from Itata keen to export to the UK. If you would like to register for the event then email info@amandabarnes.co.uk.

- You can read about Barnes’ love of Chilean and South American wine and why she has published the first authoritative guide on the continent’s wine producing countries in this interview on The Buyer here.