Changyu Pioneer Wine company which was founded in 1892 is one of China’s oldest and largest commercial wineries, and one of the largest wine companies in the entire world.

What’s exciting about Chinese wine right now?

You are now getting wines that are trying to tell you something about where they come from in China. Five years ago, a lot of quality Chinese wines are aiming for technical precision and competence, or to taste like a ‘classic Bordeaux’. Now, having achieved certain standards and technical know-how, you hear winemakers say that they want to make ‘Riesling of Shandong’ and ‘Cabernet of Ningxia’. Winemakers are also experimenting with crosses between European and native Chinese grapes. All these are surely more interesting for the consumers too.

Janet Wang is a contributing editor on decanterchina.com. Her wine writing has been shortlisted for the Circle of Wine Writers’ Young Wine Writer’s Award.

Given that China is one of the world’s largest wine producers – why do we know so little about it?

There is a Chinese saying that ‘even the best wines are afraid of obscure alleys’.

I think the main issues are to do with visibility, perceived relevance and also some out-dated general notion about what Chinese wine represents.

The reality is, most Chinese wines are consumed domestically, and cannot compete internationally on a quality-price ratio at present. Most people who say they’ve had Chinese wines, are likely to conjure up traumatic memories of cheap and fiery grain liquors or low grade grape wines made by some state-owned enterprise. Chinese restaurants are not incentivised to take a chance on new Chinese wines – because near zero historical demand means they are more interested in improving their crispy duck recipe than their wine list.

So this is an unfortunate starting point for Chinese wines wanting to establish a good international reputation.

Jean-Claude Berrouet (formerly of Petrus) is the consultant winemaker at Rongzi Winery, Shanxi province

Furthermore, if Chinese wines don’t feel relevant to the western market, in the sense that nobody cares to write about it or talk about it, then it follows consumers don’t know about it, and don’t seek out to try it, and there’s no demand so there is limited appetite for supply. It doesn’t actually matter how big you might be domestically, but if it is not relevant to the people here, then it is not making the news.

A case in point is the Chinese baijiu (grain liquor) market – 10 billion litres are consumed a year in China alone, versus the global vodka consumption of 4 billion litres a year. Or, China’s Kweichou Moutai is the most valuable liquor company in the world, having overtaken Johnnie Walker’s owner Diageo in 2017. Yet very few people know about baijiu or Moutai over here.

Is that set to change? Do you think we will get to be seeing more quality Chinese wine in the UK?

Yes! Because there are now more good wines wanting to come out of China and can offer quality, interest as well as value in a global market place, not merely as a curiosity. As a result, more distributors and promoters are getting involved. We should see more coming – especially UK being considered one of the most important and benchmark markets.

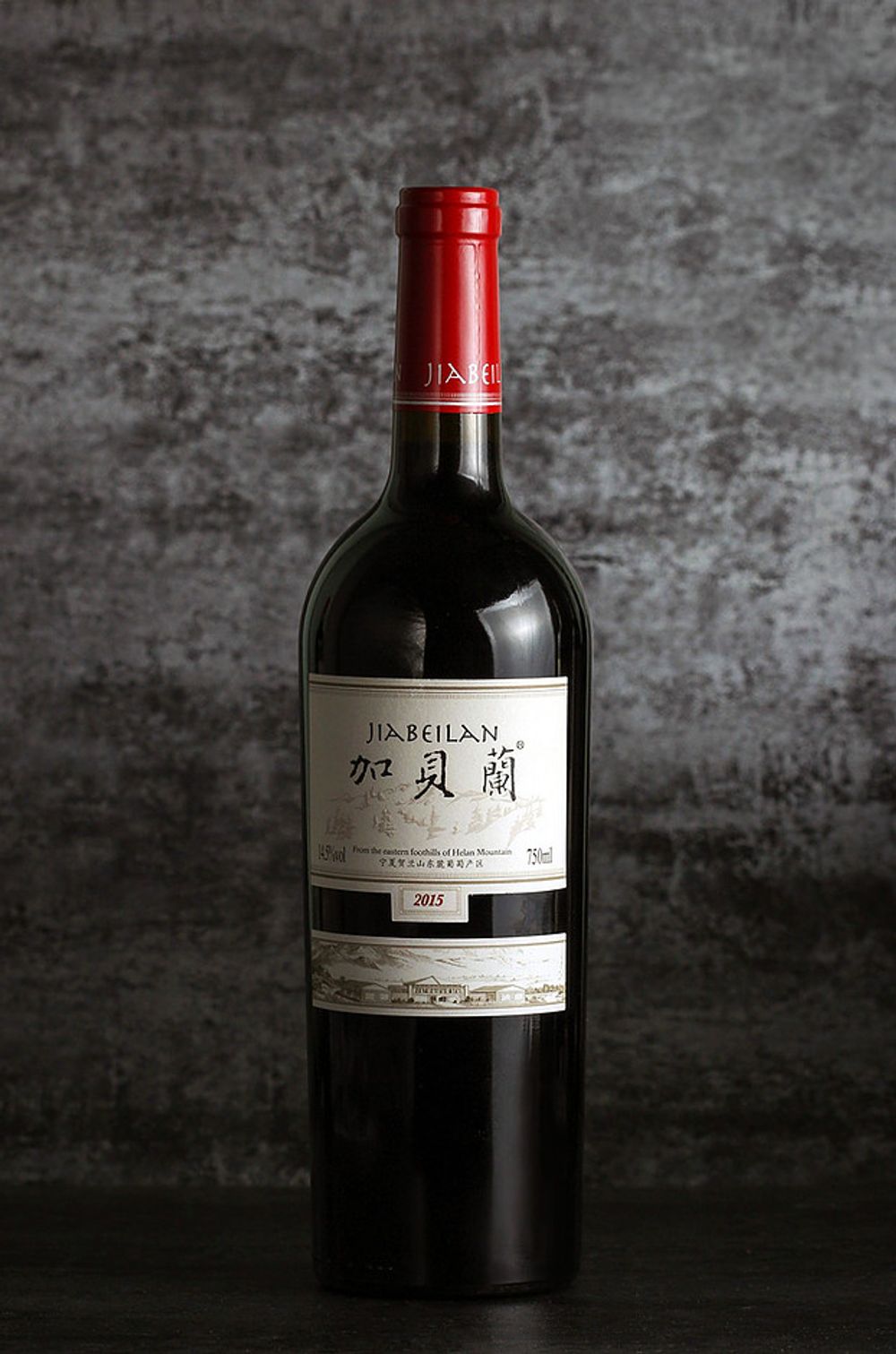

When Helan Qingxue Vineyard won the International Trophy at the Decanter World Wine Awards (DWWA) 2011 for its Jia Bei Lan Grand Reserve 2009 (2009 Cabernet) this was the highest award ever won by a Chinese winery.

Is there a set Chinese wine style?

It is not so easy to generalise Chinese wine style now – versus perhaps five years ago. Previously, many Chinese wines have been described as ‘technical’, in the sense that you can’t really fault it but it is not terribly inspiring, but now this is no longer a fair comment. However, average age of vines in China are still quite young compared to elsewhere in the world, so you’ll find more ‘fruit forward’ wines. And Chinese wines tend to be ‘food friendly’.

Is it largely indigenous grape varieties or international varieties that are proving to be popular?

Cabernet Sauvignon is the most planted grape in China. Carménère (known in China as Cabernet Gernischt) is the most established and Marselan (originally a French variety, Cabernet Sauvignon x Grenache) is a rising star variety in China. For whites – Chardonnay and (Italian) Riesling dominate.

There are interesting local varieties too, such as a white wine grape called the Longyan (dragon eye – not to be confused with a fruit from the lychee family with the same name!) Some intriguing crossbreeds such as Beichun (Muscat Hamburg x Amurensis) are making promising red wines, although they are not yet produced in large quantities so are hard to find, even in China.

If someone wants to start tasting more Chinese wine – where should they start?

I would suggest trying something from Ningxia, Shandong and Xinjiang provinces – they are the most prominent wine regions in China and will take you from the land of the ancient Silk Road in the far west of China to the other end where the Yellow River empties into the East China sea, via some unique terroirs verging the Gobi desert and foothills of once impassable mountain ranges.

In terms of varieties, try some examples of Bordeaux blends, Marselan and Cabernet Gernischt (Carménère). For whites, Rieslings tend to be more uniform in quality, although some fine Chardonnays are also available. If you like bubbly, try Chandon China (Moët Hennessy’s sparkling wine from Ningxia). For something sweeter, Liaoning province is set to become a top region for ice-wine (made from Vidal picked while still frozen on the vine).

30 hectares of new vineyards in the Himalayas produces Ao Yun, the most expensive wine that LVMH produces. (pic: LVMH)

So who are some of the producers we should keep our eye on and why?

The below list is very far from exhaustive or definitive! But they are some of the most internationally visible producers today.

Helan Qingxue Vineyard, Ningxia province. The winery is renowned internationally for its Jia Bei Lan Grand Reserve 2009 (2009 Cabernet), which won the International Trophy at the Decanter World Wine Awards (DWWA) 2011, the highest award ever won by a Chinese winery.

Kanaan Winery, Ningxia province. Besides the range of award winning wines, Kanaan is also highly recognisable for the striking wine label with an energetic black horse (it really stands out in a sea of wine bottles in a crowded tasting room – and by extension, shop shelf?)

Martin Winery, Yanhuai Valley, Huailai, Hebei province. Founded with the support of former British Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath. It is renowned for its distinctive traditional Chinese grape varieties (such as the Longyan grape).

Rongzi Winery, Shanxi province. Jean-Claude Berrouet (former Petrus winemaker) consults.

Grace Vineyard, Shanxi province. It is one of the first premium boutique wineries in China and was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in June 2018.

Tiansai Winery (Skyline of Gobi), Xinjiang province. Winner of “China Best Boutique Winery Awards” successively since 2012.

Changyu Pioneer Wine company – China’s oldest and largest commercial winery – established in 1892. Its founding father Zhang Bishi is credited with importing no fewer than 120 European grape varieties to China, including the so-called Cabernet Gernischt (Old-World Carménère). With wineries in Shandong, Beijing, Liaoning, Shaanxi, Ningxia and Xinjiang, as well as acquisitions in Cognac and Bordeaux, it is one of the world’s largest wine companies. Its vast range caters across the spectrum from basic to mid-tier to premium wines covering red wine, white wine, ice wine, sparkling wine, brandy, vermouth and tonic wine.

Shangri-La Ao Yun, Yunnan province. Moët Hennessy’s most costly wine to make is in China! (that is quite incredible considering its illustrious wine portfolio including the likes of Yquem!). The vines are grown in hundreds of small vineyards among peaks 2,600m above sea level near the Tibetan Plateau.

Other large conglomerates with multiple vineyards and interests in China include Pernod Ricard, COFCO Great Wall and Dynasty.

Martin Vineyard: one of the wineries to keep an eye on

What are the top 6 Chinese wines that every sommelier should be looking at for their list?

I will suggest 6 wines currently available in the UK:

Chateau Martin Longyan

Kanaan Winery Riesling

Helan Qingxue Jia Bei Lan

Grace Vineyard Chairman’s Reserve

Chateau Rongzi Red Label

Chateau Changyu Golden Valley Icewine

Does Chinese wine go well with just Chinese food or are there other styles of cuisine that it is well suited to?

Chinese wines can definitely go with other cuisines! You can quite happily drink a Xinjiang Cabernet blend with a steak, or a Ningxia Riesling with a Thai curry.

Interestingly, however, matching any wine (Chinese or not) to Chinese food can often be more challenging because of the way that dishes are served together rather than course by course. This is another reason why Chinese restaurants have by and large avoided the challenge of food and wine matching, however this is changing too. Some top Chinese restaurants are now designing their menu and wine list in tandem, hopefully we will see that gradually filtering through to the mainstream.

You’ve just published The Chinese Wine Renaissance. What is it that made you want to write a book about it?

I remember when I first came to the UK as a child, I felt really proud that so many people loved Chinese food! Of course the same cannot be said for Chinese wines. Yet China did have, and is now reviving, an ancient and rich wine culture, now with a global flavour. I was surprised that so little has been written about China’s wines, which are just as diverse and fascinating as Chinese cuisines.

I realised the main reason is that wine culture is very much tied to a nation’s prosperity – as my book shows, in times of hardship and chaos, winemaking is often prohibited or disrupted. So as China re-emerges from a perilous period in recent history to become a global super power, the wine culture of China is flourishing again. And, as a result, we are observing a boom in wine demand as well as production, and Chinese wines are now making inroads in the global arena.

So I feel the time is ripe for a book about Chinese wines and also its rich heritage, in English. I also feel that my multi-cultural upbringing enabled me to have a rounded perspective, and to bridge cultural concepts between western and eastern audiences. I hope this book can be a first step towards more interest in Chinese wines and I am quietly confident that one day Chinese wines will make me feel the way I felt when I first realised how popular Chinese food was around the world!

Is your book meant to be a definitive guide to Chinese wine?

Not definitive, but it is quite comprehensive in its coverage of the subject matter. I hope as a result of this book, more people will seek out (good) Chinese wines and try them, and also understand more about why a particular wine made its way here.

Of course the book has information about production regions, grape varieties, commendable producers, wine and food suggestions etc. but it is also a cultural tour of China with wine as the unifying theme. So we look at how Chinese festivals are celebrated with wine, how businesses are conducted with wine, why are the Chinese so obsessed with the health benefits of wine, why did the Chinese pay THAT much for Bordeaux cru classe, how can we use native concepts to talk about foreign wines to make communication more effective, etc.

I actually don’t think it is possible to write a definitive guide to Chinese wine, because things happen so fast and change so much in China. Facts and figures can be quite fluid and it is a fledgling industry where people are still learning and experimenting as they go along. I hope this book touches on all the important wine themes in a China context, and lays the foundation bricks of knowledge and ideas. After that there’s the internet for more current affairs! (I will also post news and updates on my blog at winepeek.com)

Who is it intended for?

My first attempt at writing a book blurb goes: ‘If you like wine, and have heard of China, then this book is for you!’

I am still determined to use this line somewhere!

I think you will enjoy this book if you like trying new wines from different regions, if you are interested in delving into various cultures and want to know the backstories of what brought about a new phenomenon.

Rongzi Winery

Is there a particular angle or stance you’ve taken?

My main premise for the book is in the word ‘renaissance’, in the book title. I really want to show the reader a wine culture spanning thousands of years and that shares a fate with the rise and fall of civilisation. I think this macro view of Chinese wine culture is essential if you want to understand the pace and ambition of the modern Chinese wine industry, and Chinese people’s relationship with wine.

Talk us through the process of how you start writing about such a massive subject.

The whole thing started off from fragments of impressions, thoughts and tasting notes I jotted down – I had the great privilege of meeting the late Jean-Paul Gardère at his home in Bordeaux (chief winemaker at Latour for 25 years) and hear him talk (via translation) about his working principles, and it struck me how many parallels I could draw from his words to various schools of Chinese philosophy.

I grew up with an interest in Chinese classics and history, so I felt compelled to write down thoughts from such conversations. This ignited an interest to learn more about wine, and the more I delved into the subject, the more complexities and intrigues are revealed – it sucks you in forever. And all the while, I was also exploring these concepts by drawing from my own experiences from a dual-cultural upbringing.

Over time I organised my thoughts into short essays, and then organised the essays into themes. Then from the themes, I went back to talk to more producers and merchants, asking them their views and experiences on certain topics that I wanted to write about, such as how to talk about wine to a new consumer market.

By this point I have got a framework in mind, and decided to have three parts to the book:

Part I, by way of an ‘aperitif’, introduces China’s wine industry, its major wine-producing regions and the evolution of grape wine among the various types of alcoholic beverage that make up China’s wide repertoire.

Part II is a ‘mixed case’ that covers enduring wine themes in the context of China and explores the distinctive fusion of cultures in wine and beyond.

Part III is a ‘vertical tasting’ of the dynastic history of China, illustrating the evolution of wine alongside the evolution of a civilisation.

Then it’s just a matter of colouring in with contents for each section. I had most of the material for Part II already from interviews, conversations, notes and essays. This is the section where I have put in a lot of my own observations and thoughts. Then I wrote Part III, which is essentially a brief history of China through a wine glass, which then led me to write about the present day and look to the future, which turned into Part I.

All pics copyright Panda Wine except the Himalayas shot from LVMH