“Indigenous varieties are the strength of Georgian wine and we try to make modern accessible wines that reflect them,” winemaker Vlad Kublashvili says.

“So, I’m off on a press trip to Georgia,” I told my bemused family, with whom I have spent much of the year firmly locked down at home. “Pass the milk.”

“Are you really going away Dad?”

Well, no. Like other generics in this grim year, the National Wine Agency (working with Swirl Wine Group) has gone virtual, showing hacks this stunning Caucasus country via Zoom and some mini tasting samples, with a few Georgian condiments thrown in (I can recommend wonderfully aromatic Svanetian salt and the rubbery, moreish Smoked Sulguni cheese). Oh and some black tea, presumably to keep me awake during the 7 hour flight to Tbilisi that I wouldn’t be taking. Having not received an invite to last year’s actual press trips, I felt I should accept.

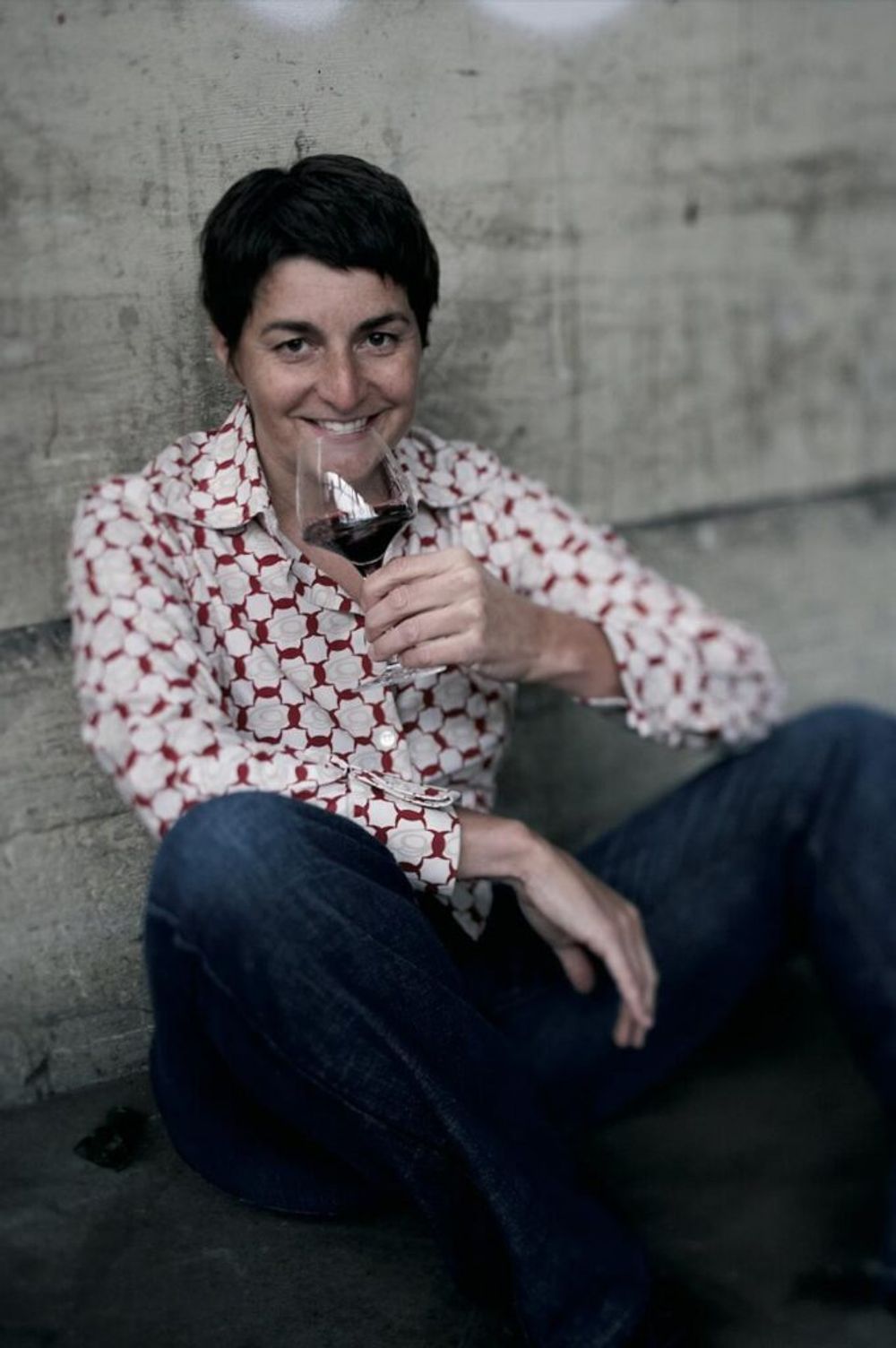

Isabelle Legeron MW: set up RAW Wine

The move away from the Russian market

Georgia and I go back a long way, though we became estranged. I first visited in the early Noughties wearing my political journalist hat, travelling by Soviet helicopter to mountainous Svaneti to interview controversial President Mikheil Saakashvilli. Visiting a few years later with natural wine savant Isabelle Legeron MW – the first French person to get the Master of Wine – I tasted mainly amber and natural wines in sheds, basements and tiny wineries, made from a wide range of this ancient winemaking country’s 500+ varieties.

The impression I was left with – reinforced by subsequent, largely unfocused UK tastings – was this: Georgia’s wine industry is dynamic and fast-evolving after years of post communist stagnation. It is moving away from the Russian market, a process fuelled by political tensions with Moscow (although it and Ukraine still account for 75% of exports) and has been upping quality as it boosts exports to the UK and other markets.

But it is also deeply chaotic – as Georgians never tire of telling you, this country of 3.7m (probably along with neighbouring Armenia) was where wine was first produced 8000 years ago and today almost everyone seems to make their own wine. With land and property issues now largely sorted, the number of wineries has exploded from around 80 in 2006 to almost 1000 today. This has made finding reliable and good producers a challenge but, increasingly, a worthwhile one.

Despite Georgia’s 8000 years of tradition, the modern wine industry here really dates back only 20 years

Quality has improved because, frankly, it had to: if you are exporting into today’s competitive global marketplace you can’t produce the same sweet sub-standard stuff that sold in Soviet times. The break-up of the large wine companies that once dominated has been a plus, with many transformed into quality-focused entities eager to build up a customer base, aided in many cases with western finance and advice.

Meanwhile, a growing number of boutique producers – many using traditional clay quevri but also more modern techniques – has added further appeal, suggesting Georgian wine is moving forward with confidence.

But the best news is that winemakers are more actively exploiting Georgia’s rich diversity of grape varieties, which are so numerous that descriptions of them fill almost one quarter of Lisa Granik’s excellent and highly accessible new book, The Wines of Georgia (published by Infinite Ideas).

White Rkatsiteli and red Saperavi (both used as high volume workhorse grapes in Soviet times) dominate, accounting for 48% and 10% of total plantings, with the former described as Georgia’s Chardonnay because of its versatility and the latter described as its secret weapon – capable of making big wines but also as Abbott says, “of carrying intensity of flavour and depth without too much alcohol.”

However, winemakers are using more Kisi, Chinuri, Tsolikuri and other white varieties, with 70% of total acreage planted with white varieties.

Kakheti remains the biggest volume region, accounting for some 70% of plantings but others are growing in importance, suggesting the emergence of a more coherent PDO system cannot be far off.

The net result is that Georgia, whose total wine production is a little bigger than that of New Zealand but a little smaller than Greece, is now very much on the up.

So what about the wines themselves?

Over our two day Zoom tour, Sarah Abbott introduced us to four wines each from six very different producers, all with representation in the UK; Vachnadziani (HN Wines), Dakishvili (Clark Foyster) Tbilvino (Berkmann) Teliani Valley (Boutinot), Ori Marani and Lagvinari (Georgian Wine Club). Samples for the last two never arrived/were spoiled, so I’ll focus on the others.

Dakishvili Family Cellars is the archetypal quevri-focused producer – just 50,000 bottles – owned by Gogi Dakishvili whose earlier transformation of Teliani Valley was one of the key steps in helping Georgian wine back to health. All the wines shown here – Saperavi 2017, Kisi 2018 and the Orgo white cuvee, a masterful and complex blending of three Kakhetian varieties – were impressive so too was the more commercial, bright and crunchy Saperavi 2018 he makes for Schuchmann, a medium sized (1.5m bottles) German JV operating since 2008. Tasting these wines leaves you with little doubt as to how Gogi Dakisvili – who says the secret to good winemaking lies in the vineyard – got his impressive reputation.

Tbilvino is a big producer (5.4m bottles a year but with the capacity for 7.5m) best known here for the amber quevri wine it sells through M&S for £10. First founded in 1962 it has been thoroughly revamped since being bought by the Margvelashvili brothers 20 years ago who revamped the main Tbilisi winery in 2009 and built a new one in Kakheti three years later. The focus is on good solid commercial wines and the Saperavi 2018 – made in stainless steel from Kakhetian fruit – is a typical example, bright cherry fruit on the palate.

Working the quevri at Dakishvili Family Cellars

Established in its present form in 1995 and now producing up to six million bottles of 60 different wines, Vachnadziani is Georgia’s biggest producer, specialising in native varieties including Krakhuna, Mtsvane and of course, Rkatsiteli and Saperavi, but not sacrificing quality.

Focused on the Kakheti and Imereti region, winemaker Vlad Kublashvili says the strength here is that Vachnadziani owns its vineyards including a new one currently being planted in mountainous Kartli.

“Indigenous varieties are our strength and we try to make modern accessible wines that reflect them,” he says.

The highlights here were the White Krakhuna 2018, a rare variety from Imereti which nearly became extinct back in 2004 but is now being replanted. This is a wonderfully rich, quite full bodied wine, with lovely peach notes, and with a trade price of just £9.48. Even better albeit pricier is the Otskhanuri Sapere 2014, another rare variety from the same region. This is a hugely complex quevri wine which Kublashvili says gains much of its character from green bunches being left in the mix when the grapes go into the quevri. The entry level Saperavi 2019 (with a trade price of just £7.79) is an unadorned but attractive, bright and fruit-forward example of the variety.

Teliani Valley was one of the industrial producers that in the early Noughties frankly helped sour my impression of Georgian wine. But that was before previous winemaker Gogi Dakishvili got to work with this historic producer. It is still big with some 4m bottles of 30 different wines being produced, but quality has been transformed in an ambitious, still ongoing process.

This is reflected by the five bottles that were selected by Boutinot for the UK market and attractively and carefully packaged to “appear more Georgian.” The three distinct takes on Sapevari, the TV 2019, TV Unfiltered 2018 and TV Glekhuri Kisiskhevi Quevi 2019, are all impressive, showing the depth and versatility of the variety, whilst the two amber wines (TV Kakhuri No 8, 2019, a blend of Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane and Khikhvi and the TV Glekhuri Kisi Quevri 2019) are complex but moreish introductions to the style, which should widen its appeal.

Matthew Jones, Boutinot’s product manager for central and east Europe, says the wines have been doing very well.

“Georgia’s moment is certainly coming, and has been part of a well executed wider strategy to help shed an over-reliance on the fickle Russian market by striving to create interesting wines that are proudly and uniquely Georgian, as opposed to trying to replicate more familiar Western styles,” he says. “Teliani has a team of innovative young winemakers who are given the time, equipment, fruit and support to create really exciting things and putting in place the philosophy and culture needed to build for the future.”

The number of wineries has exploded from around 80 in 2006 to almost 1000 today

So, in conclusion…

Despite Georgia’s 8000 years of tradition, the modern wine industry here really dates back only 20 years. During this time it has rejoined the world from which the Iron Curtain had excluded it, and learned a few new tricks. Right now, we are looking at an industry that is getting its act together with the likes of Teliani Valley and Vachnadziani looking like precisely the sort of progressive benchmark producers Georgia needed but lacked. Both new to the UK trade, they have done very well despite the Covid-cursed environment. These are appealing, well-priced wines that are commercial but in a good way with a distinct Georgian edge.

Alongside these are the exciting niche producers that appeal to wine purists, but with quevri wines accounting for just 1% of total production, mean rather less for the wider industry.

But with both categories now in the ascendant, these are exciting times for Georgia. Time to go back, I feel.