“The entire industry should implement a clear vision to maintain price points at sustainable levels for growers and producers alike. This means that for premium wines, you must support the price by offering a wine that represents great value versus international counterparts,” writes Lambert.

English sparkling wines are now well established, both in this country and on the world stage. This is fantastic progress but rather overshadows our still wine which is just 28% in volume with sparkling accounting for 72%.

It’s easy to see how this happened. A combination of cool climate, variable yields and high labour costs means that the raw material cost is high for English wine. This means that at the beginning of our English wine journey, the focus was on planting traditionally cool climate varietals such as Reichensteiner, Huxelrebe and Dornfelder which were able to produce crop, not necessarily for the potential of the end product.

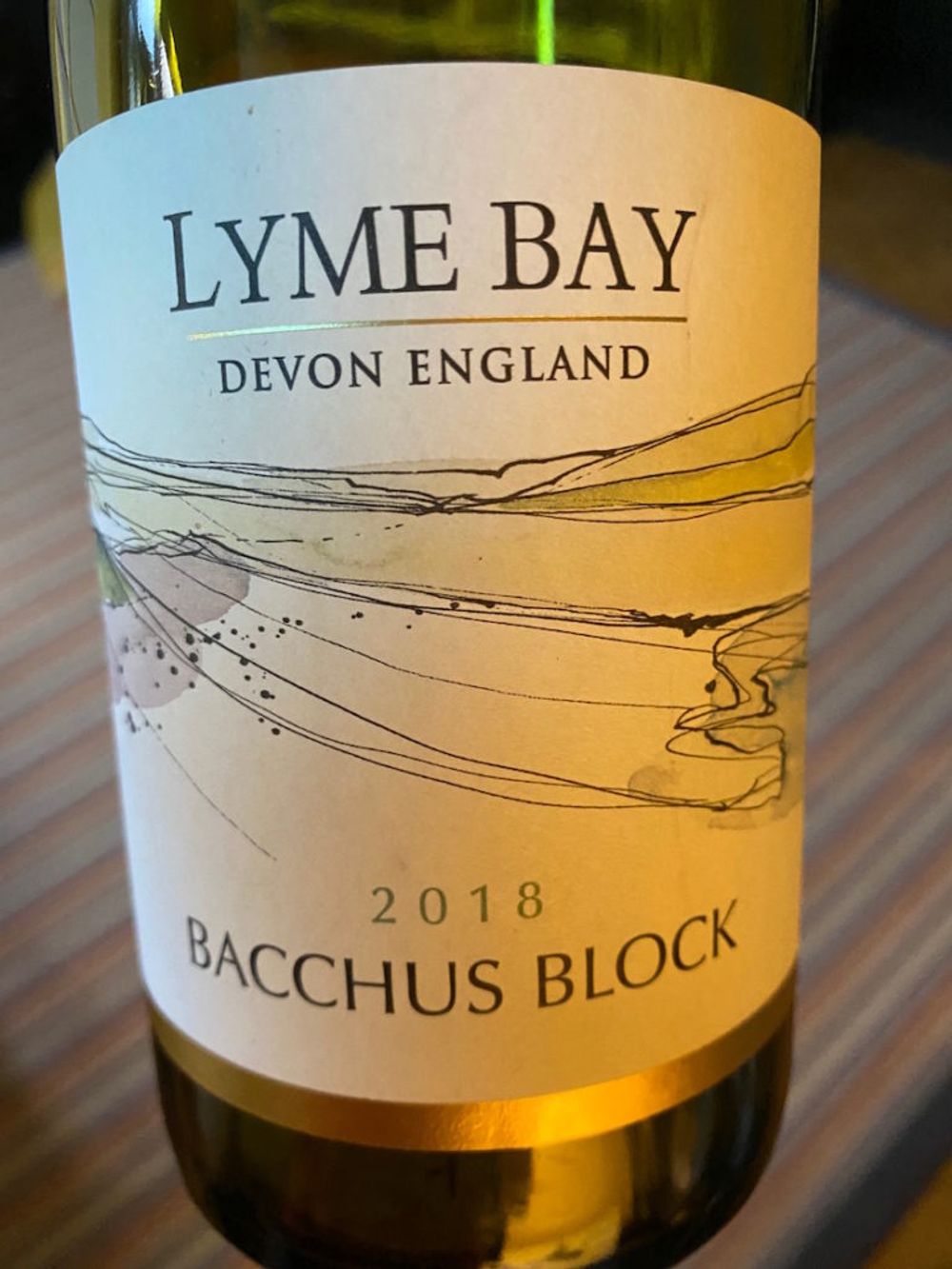

In terms of still wine, Bacchus is a grape which has established itself as a consistent and reliable still wine specialist in the UK – aromatic, good acidic balance and not hugely unlike a light Sauvignon Blanc in character. The UK’s slower, cooler growing season enables great flavour development and retention of that symbolic crisp acidic backbone that typifies the style.

Sadly, there are some well-known varietals that will remain unsuitable for growing in the UK for a considerable time – don’t expect to see the likes of English Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon any time soon, for example.

Varietals such as Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay, are widely planted and grown but are used for sparkling wine rather than still.

So where are all the still wines? The devil, of course, is in the detail.

James Lambert, managing director Lyme Bay Winery

Rewind 20 years or so, and many of the grapes in the UK were those unheard of Germanic varietals. Safety-first vineyard owners did indeed throw caution to the wind in planting the famous French trio, but the risk was mostly mitigated by using clones of each variety more suited to making sparkling wines, not still.

This distinction is key. The grapes may wear the famous varietal tag, but the characteristics are different in some vital ways. First, bunches tend to be looser which allows for better airflow and less contact between berries, meaning that they are less susceptible to disease pressure. Good for yield, but not good for concentration of colour.

Second, berries tend to be larger. This reduces the potential flavour in the grape as the ratio of surface area to pulp is decreased (most of the precursors are located on the inner surface of the skin itself), and dilutes the sugar content (thus potential alcohol levels). All good for sparkling wine production where you’re looking to develop flavour from the secondary fermentation, less good for still wines.

Some wineries have, through very careful cellar management and use of chaptalisation, managed to create both whites and reds (and rosés) from these clones. However, these wines have tended not to be overly consistent, and for entirely logical reasons, do not come close to matching their French counterparts.

However, there are signs that some ambitious producers are looking to clones in more detail. Chapel Down has produced a consistently good Chardonnay from their “Kit’s Coty” vineyard, likewise Gusbourne has also produced some great Chardonnay (“Guinevere”). Both utilise Dijon clones specifically designed for the purpose. The reviews and awards each marque have achieved in recent years points to the correct strategy.

The quality producers of still wine in England are looking at clones in more detail

Lyme Bay Winery does not own a vineyard. We take the view that the UK is small enough that to limit ourselves to one patch of it would be counterintuitive. This allows us to assemble complex blends made from specific clones of grapes that give truly unique characteristics from growers across the country.

Over recent years, and working closely with viticultural consultant Duncan McNeill, Lyme Bay Winery has identified growers in pockets of land uniquely suited to growing and ripening the right clones of the right grapes, to levels required for prestige still wines. We have found that Pinot Noir and Chardonnay are consistently achieving French levels of ripeness from an area just north of the River Crouch, in Essex.

So, how can we encourage more production of English still wine?

We cannot escape from the fact that grape growing is expensive in the UK no matter what the intended purpose of the grapes once in the cellar. Insisting on techniques designed to maximise ripeness only increases the costs. For example, as producers, we demand lower yield which allows for riper bunches. For the grower, this comes at a cost as yield is reduced.

Essentially, growers and producers need to work together on a sustainable long-term strategy where the supply agreement is geared around quality, not quantity. This route is, of course, not without risk. If you are encouraging growers in the right areas to plant still wine clones more susceptible to disease, and construct a supply agreement that gives long-term security with the emphasis squarely on quality, you are committed to creating a wine that can then justify the higher costs of the raw material.

This means that you cannot short-cut the next stage, i.e. making the wine. You need the right people, a clear strategy, the ability to invest in the right equipment which respects the quality of the fruit, and above all you need to create a culture of quality where all staff members in every department are bought in.

As the UK is a marginal climate, high quality wines made from varietals such as Pinot Noir and Chardonnay will come at a premium. We knew this when we launched our first English wines in 2015, and it is still true today.

Outside of Lyme Bay Winery, the entire industry should implement a clear vision to maintain price points at sustainable levels for growers and producers alike. This means that for premium wines, you must support the price by offering a wine that represents great value versus international counterparts. This is equally true for wines at lower price points.

Above all, the wines must showcase the potential of English wine growing, and must celebrate the diverse viticultural regions and approaches each grower takes. If we can do all of that, we’re allowing the wine to speak for itself, justify its place, and tell its own story. It is truly an exciting time for the future of English still wines.