Buyers will get the chance to see at this week’s London tasting how Georgia is combining modern winemaking methods with its traditional ways to produce wines that can have really make a difference to your wine lists.

Sarah Abbott MW has been captivated not only by the quality of its wines, but how much wine is part of Georgian culture

Wine consultant, Sarah Abbott MW, has been working with Wines of Georgia to help its producers better understand what opportunities they might have in the highly competitive UK on-trade market as well as identifying the styles of wine she thinks are best placed to succeed here. She explains why she is so excited about Georgia’s future in the premium on-trade.

Georgian wines have had an up and down history in the UK wine market. Why do you think they are still finding their way?

Wine tells the story of its country. In the past three decades Georgia has come from civil war and great hardship to astonishing recovery. I have never seen a country that identifies itself with its wine as much as Georgia. But until relatively recently, the Georgian wine sector did not have the structures and support that we take for granted in France, Italy, Spain and Australia. And most Georgian producers have really only been focused on sustained exports to the UK for the last five years.

Georgia is a former Soviet republic, and that legacy is deep rooted and heavy. Georgia was the breadbasket and vineyard of the Soviet Union, and they were used to servicing that market. It is a market so different to ours that it is almost like exporting to a different planet. Here, it’s all about brand building and continuity.

Is Georgia still recovering from seeing its wines barred from sale in what was its core Russian market?

When President Putin banned imports of Georgian wine in 2006, it was disaster for the Georgian wine sector. Or so it seemed. But Georgians are incredibly creative and determined, and the story of the last 10 years has been the story of Georgian wine moving away from being the darling of the CIS to being able to compete on the world stage of wine.

Georgia now has a national wine agency, which is part of the Ministry of Agriculture. Wine is a priority product for the ministry. The country itself has transformed infrastructure and entrepreneurial expertise in the last 10-15 years. Wine is booming. Tourism is booming. The World Bank rates Georgia as the top CIS (i.e., former Soviet Union) country in ‘ease of doing business’. Investors have the confidence to support existing and new vineyards and wineries, and the number of wineries has exploded over the last five years.

2016 was the best year ever for Georgian wine exports to the UK. Georgian wines are being imported by specialist on-trade suppliers such as Clark Foyster, as well as by a Eastern European specialists such as Turton Wines, and Georgian Wine Club. They have listings in Marks and Spencer, The Wine Society, and Waitrose. These retail listings are important because they start to familiarise diners with Georgian wines.

Then the national wine agency got the go-ahead for the first ever annual program to support UK exports, and that’s where we are now.

Georgia is blessed with stunning vineyards surrounded by mountain ranges

What challenges do you think Georgia faces compared to other East European countries?

The biggest challenge is that so few people know where it is. Even now in the UK when we talk to consumers – and even trade – we have to say “The Country of Georgia, not the US state”. And it is that bit further away, so we are working on supporting some logistical operations to bring down shipping lead times, and costs.

But other than that, Georgia is in a fantastic position. The wine potential is huge and is increasingly being met. They have thousands of years of unbroken wine tradition, hundreds of native varieties, diverse wine styles, and a wide range of price points. It has not focused on easy drinking low cost international varieties. In fact, Georgia doesn’t really do large volumes of low-cost wine in the way that Romania can, or that Moldova could do. The terrain is too mountainous, and the grip of the indigenous varieties is too strong. Georgia’s positioning is more like New Zealand in terms of price and quantity. It has varieties that you can’t find anywhere else. And of course, Georgia has Qvevri wines, which are a specialist wine style with niche but powerfully emotional appeal.

Also the country is a gem. I have been lucky to visit and enjoy the hospitality of wine nations across the world, and Georgia just captures your heart. It is so beautiful, and so vibrant, and the Georgian agencies have been visionary in integrating wine tourism, food tourism and cultural tourism.

Anyone who has been to Georgia will tell you about the quirky, soulful, romantic appeal of the place. Tbilisi – the capital city – is buzzing as one of the arty, hip East-West destinations. The world U20s rugby is being held in Georgia now, and the Wine Show has just filmed a program there. The countryside is so beautiful and wild and un-spoilt. Georgian food is fabulous too. It was the ‘fine dining’ of the Soviet Union and is increasingly being covered by European food writers and cooks.

What opportunities do you think there are for Georgian wines and why now?

Wines of the Eastern Med are really established as a new wine category. Major importers such as Hallgarten have really got behind this, and it’s matched by developments in the on-trade. You have restaurants such as the Ottolenghi group, and also independents taking inspiration from top quality mangal, Levantine and Caucasian food. Georgian wine is perfect for this food and this vibe – they are fresh but vibrant and they offer something of an adventure, which is very appealing to the demographic of these places.

What styles of Georgian wine will work best in the UK?

The dry whites are lively and gently aromatic. I was tasting in Tbilisi last week with Isa Bal MS of the Fat Duck, and we both found ourselves comparing the whites to styles such as Gruner Veltliner and Alvarinho. The aromatic dry whites are generally unoaked, have naturally fresh acidity, creamy textures, and food-friendly length.

The hero of the dry reds is Saperavi. I get very excited about this grape, and I’m not alone. The Saperavi styles range from bright, red-cherry and lively to sumptuous, spicy, and oak-aged. Bal is selling 40 plus bottles of Saperavi a week at the Fat Duck. Saperavi has huge potential, and is probably the noblest grape that most people have never heard of. We are holding a series of master classes and events to focus on Saperavi in 2017.

Funnily enough – because I had thought it would be a tough sell – we are getting a lot of interest in the off-dry reds. These are an historic wine style of Georgia. They are made from late-picked Saperavi (and other grapes), and the Georgians serve them lightly chilled with spicy dishes and kebabs.

Georgia is also making good sparkling and rosé styles, although at the moment these are being snapped up domestically. Hopefully we will see more of those in the UK soon.

Can you explain Qveri wines to us?

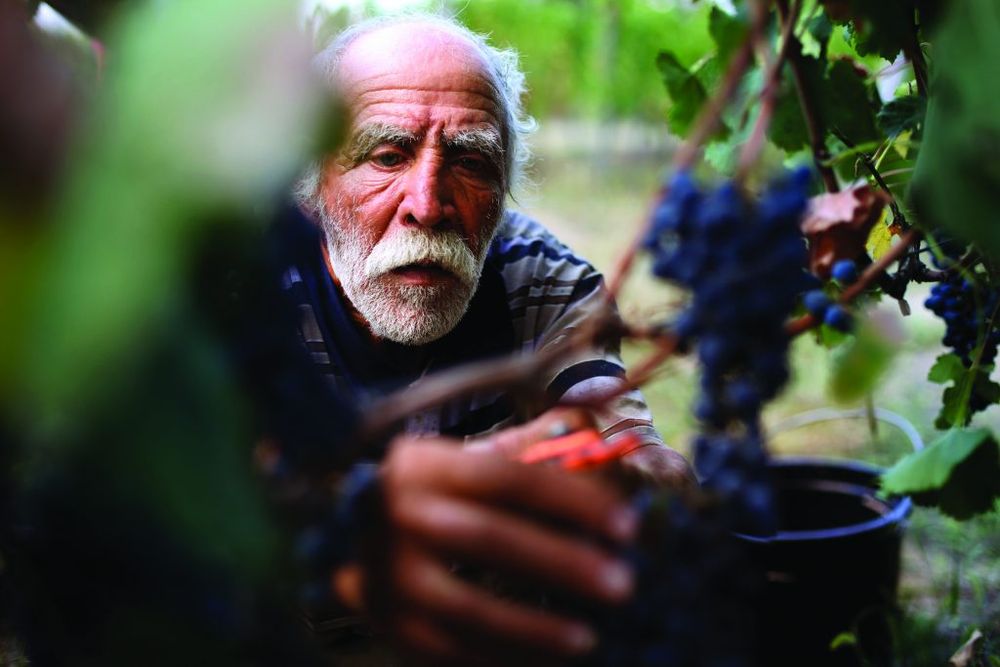

Traditional winemaking techniques not only make unique wines but they add to Georgia’s allure

These ‘orange’ wines are probably the most vibrant and interesting sector of wine production in Georgia right now. They have the aromatics of a complex white wine, the texture of a red, and a rich and generous finish. There’s a lot of misunderstanding about Qvevri, and about the wine style. Qvevri are not some hippy indulgence. They solve a lot of winemaking problems in terms of temperature control, extraction, effective alcoholic and malolactic fermentation, and clarification and stabilisation. And they do it with reduced requirement for inputs – if that’s your bag.

You will see Qvevri cellars (‘Marani’), in some of the most high-tech wineries in Georgia, alongside shiny stainless steel and rows of barriques. New London restaurant, Darjeeling Express, which opens later this month, is featuring an extended Qvevri Wine selection on its wine list because it has found the style goes so brilliantly with spiced and robust foods.

Some Qvevri winemakers follow the ‘natural wine’ route. That is partly because Qvevri makes it easier for you to do that. There is also is a sort of spiritual dimension to Qvevri that any Georgian will recognise– the connection to the earth, and to the past generations of winemakers. But there are many winemakers using Qvevri alongside the conventional and controlled methods of wine making. Both are valid and valuable, and have their markets.

Which are the main wine growing regions of Georgia?

There are five main growing regions in Georgia. They are delimited and protected by the national wine agency. Within them, there are 18 appellations, with another five about to be approved.

The biggest wine region is Kakheti, in the east of the country. It is relatively close to Tbilisi, and is very accessible for wine tourism and day trips from Tbilisi. The climate and culture here is influenced by Persia, and the warm air from the middle east. Kakheti is known for rich reds from the Alazani River Valley, and for the deepest and most structured styles of Amber wine.

Kartli is another major wine region. The vineyards hug the foothills of the mountains in the Mtkvari River valley. They are quite high – 400-700 metres above sea level. Delicious aromatic whites come from here, including the Mtsvane family, and Chinuri. Shavkapito is a delicious perfumed red grape from Kartli.

Imereti is west of Tbilisi, and pretty much in the middle of the country. It makes aromatic but creamy white wines – they remind me of that fresh richness you find in Swiss whites. There is a project to reintroduce many Imeretian indigenous grapes back to the region, including some intriguing scented reds. It’s a wild, mountain place that was neglected wine-wise during the Soviet occupation because it’s a craggy place that is quite difficult to cultivate. It is now greatly prized for the diversity of terroir and varieties, and the racy intensity of the wines. The Qvevri wine styles from Imereti are lighter than in Kakheti. Tsolikouri is a delicious textural white grape from Imereti, and Otskhanuri Sapere is an exuberant, juicy red.

Racha – Lechkhumi

This is another mountain region, in the north and bordering Russia. It is beautiful, cool, green and wild. Wine making here was kept alive by a handful of families during Soviet times – it is a place of manual viticulture, not efficient volume production. Many wines from this region are not exported, as they are highly prized by Georgians and snapped up by the hip restaurants of Tbilisi and Batumi. But we are starting to see more in export markets. They have unique grape varieties in both white and red. You are most likely to see the scented reds Aleksandrouli and Mudjuretuli, although there are small plantings of many more.

Guria

This region borders the black sea, and is the home of Colchis (of Jason and the Golden Fleece fame). It is one of the oldest centres of viticulture in Georgia, and therefore of the world. Georgians consider Gurians to be a bit crazy, which is saying something. The wines are influenced by the warmer, sub tropical climate. Fruity reds and lovely rosé are made here, and Chkhaveri is the grape you are most likely to see.

- You can register and attend this week’s Wines of Georgia tasting here. It takes place on June 15 between 11am and 4.30pm at Carousel London, 71 Blandford Street, London, W1U 8AB. It includes a special masterclass by Sarah Abbott MW and wine writer and producer, Robert Joseph,on Saperavi at 10.30am. For more details contact Madeleine Waters at madeleine@swirlwinegroup.com.