The Dönnhoff visit was part of a five-day trip to discover different philosophies, planting and experiments in making Riesling.

At Dönnhoff, it’s hard to know where to begin. I could write an ode to Dönnhoff.

Here in the Nahe, the soil composition is strikingly varied from vineyard to vineyard. The Nahe is a smaller and cooler valley than the Mosel (the Moselle River also regulates temperature more because it is larger), so inclination, sun and slate play crucial factors. Vineyards vary in altitude from 120-280m, and Helmut Dönnhoff pauses to reflect on global warming.

Helmut Dönnhoff, Nahe, July 2018

“Higher can be good, for the future,” he muses.

Speaking of global warming, 2018 has seen enormous production. Dönnhoff’s son, Cornelius, has now taken over the day-to-day work in the vineyard. As Helmut and I stroll through the Hermannshöhle, green harvest bunches are on the floor everywhere. He winces remembering poor vintages, but it is in the name of quality, and this aspect of the domaine is now under Cornelius’ direction.

Dönnhoff is entirely certain of one notion – that every vineyard has its own special talent. “We must take the best product that the vineyard can produce; I’m always looking for the vineyard’s own talent.”

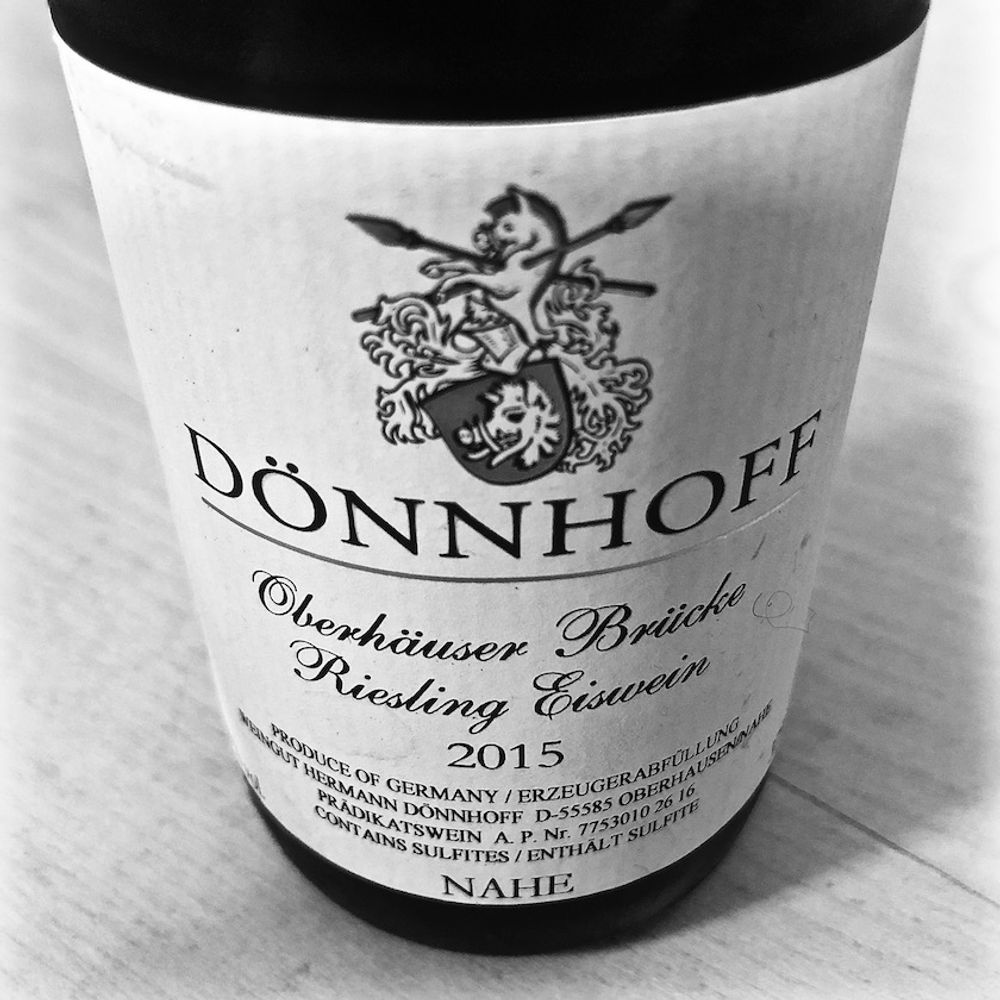

For example, Dönnhoff strongly believes that the Hermannshöhle, with its steep, south-facing slopes, grey slate and volcanic basalt, has a particular talent for dry and noble sweet wines. Meanwhile, his Oberhauser Brücke has a ‘special talent’ for dry wines and for eiswein, a wine only made in certain years (fewer and far between due to global warming), of which we tasted the 2015 vintage.

It is a wine that brings total awe and makes you envision angels pouring nectar down for us to bottle. It is nectar, beautiful gold-wound thread in vinous form that is such a unique combination of nature and human guidance.

The 2015 eiswein: nectar from the gods

Speaking of Riesling, Dönnhoff continues:

“Riesling has two talents. Outstanding dry and fruity styles. Here we can have both. The reputation of the dry style is a result of global warming. In 1971, 98% of wine was made in a sweet style. Nobody wanted or asked us for dry; that only came in the 1990s when sommeliers began to seek them. Before, the dry Rieslings were more basic in quality and cheaper in price. It has happened step by step.”

“For me, I like both. I have two children in my cellar: the dry and the sweet. For the past 20 years, I have been looking for my children in the vineyards – some can produce dry, some sweet, and some can do both.”

The most important aspect of vinifying at Dönnhoff is purity. Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc goes into new wood for the first eight years approximately.

“I decide when I can no longer taste wood, and thus readiness for Riesling. When you look for Riesling – you want pureness and clarity; it is thus a puristic idea like in classical music. Everything must taste correct – I want to taste what I see. It is a naked wine.”

“Higher can be good with global warming”

Speaking of yeasts, Dönnhoff smiles and ponders. “It is difficult for dry Rieslings when we harvest so late as the cellar is too cold for fermentation to start on its own sometimes. Of course, if yeasts from the vineyard start the fermentation, then they do and we welcome indigenous fermentations with many of our wines. However, if the wine sits alone, having not started at all because it is too cold, for over seven days, then this is also not healthy. It is a mistake to say yeasts must only be “natural.” We need them to convert sugar to alcohol. Yeast isn’t necessarily terroir – the vineyard makes the wine.”

Malolactic naturally never occurs here. Dönnhoff laughs, “if you had asked my dad if malo occurs, he would have said, what is that? Can I eat it?” It is a cool cellar and with such low pHs there is no tribe of malic bacteria.”

Speaking with Dönnhoff is to speak with somebody who makes the whole world slow down for a little while. His view on wine is philosophical; “the time we have, in this moment, is to show our own original paths in the world. We must show this part of the world to others; it is so wonderful that nature gives us something that lets us show our place and our hemisphere.”

I walk with him through the warm German night air with its heady, delicious freshness that is simply impossible to capture on paper, but which gives scents of the North, and of wild heathland and life.

Dönnhoff nods. “My job is to convey this. You are getting a feeling for the air here; this is what we need to show through our wine. It might not be the best, but it needs to show where it came from. I want our wines to be full of life, to be charming – to give you feelings.”

Christina Rasmussen travelled across Germany with Awin Barratt Siegel to get under the skin of Riesling and Pinot Noir.