Armagnac is traditionally only distilled once compared to Cognac’s double-distillation. It is this and the use of different barrels over a long period of time that gives Armagnac such distinction.

Gascony, the home of Armagnac, is a region like much of France that lives life both seasonally and off the land. This is goose and duck country, they appear on every menu in one form or another wherever you go. In that symbiotic way that the French so often do, the drink created to match them works perfectly.

Created from just a few principal grapes – Baco, Folle Blanche, Colombard and Ugni Blanc – and then the slow magic begins…

Armagnac falls into the brandy family of spirits and is the oldest produced in France, but where it differs is in the style and character of production.

The big brandy players who want to play with big numbers, Hennessy, Courvoisier, Remy Martin and Martell by definition completely miss the point of Armagnac – the craft and artisanal heritage that focuses on tradition, long running family houses where secrets are passed from father to son or in many cases to daughter.

The use of the descriptor ‘and daughters’ is not some modern ‘hipster’ affectation it is simply the way it has always been done here, as I was to see on my travels through this beautiful part of southwest France.

Strictly governed by appellation regulations the Armagnac region covers Bas-Armagnac, Armagnac-Ténarèze and Haut-Armagnac as defined in 1909 and the recent addition of Blanche d’Armagnac, introduced to allow the production and export of clear, unaged spirits.

Armagnac is traditionally aged in barrels often blended and sold as ‘vintages’. If a blend is used then the youngest of the blend will be the age describing it.

The process of single distillation gives the final pre-aged spirit more flavour and character than cognac, which is typically distilled twice.

The alcohol levels are between 50% and 58% at this stage, some producers will age then dilute to the minimum 40% at bottling stage but many prefer that extra few percent.

But this is just the beginning of the journey. Many houses will distill the different grapes separately and then blend after barrel-ageing has occurred.

This requires levels of skill only obtained through decades of experience.

As I drove through poplar tree-lined roads, said to have been planted by Napoleon to give his troops shade, the 37,000 acres of land used for vines in the strictly controlled creation of Armagnac unfold before me. Nestling at the foot of the Pyrenees this gently undulating country is quite beautiful in autumn.

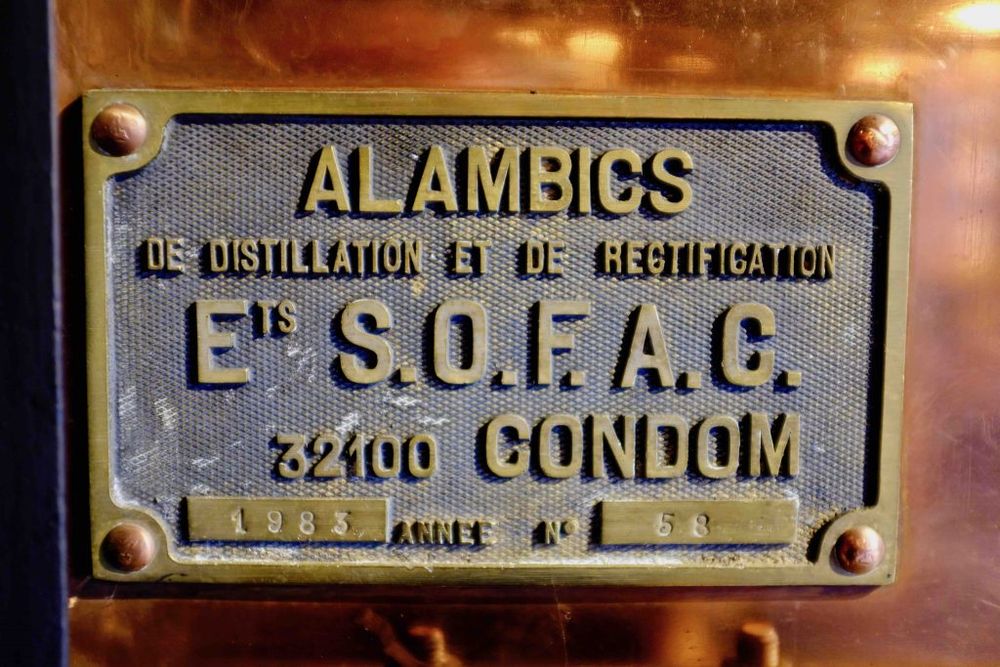

It’s also distilling time, typically the end of October through to mid-November, but this can vary depending on the weather and availability of the local ‘alambic still’ the mobile distilling machine.

These Heath-Robinson like devices are a wonder to watch working. Made of copper an alambic will contain two chambers one with a serpent coil inside surrounded by the cold wine which is then heated gently either by a wood fire or gas (which gives a controllable temperature).

The vapours are then condensed with the use of a series of small hat-like configurations within the second chamber and trickle out and are then barrelled.

But it is a complicated balancing act of: getting the right temperature, knowing when to dispense with the heads and tails or rectification of the distillate, and when the desired alcohol levels have been reached.

Several distilleries I visited were at this stage and I watched as they test, taste and calibrate their machine to produce the desired liquid. This is a 24/7 job that can take several weeks depending on the year’s harvest. Often two men (sometimes father and son) will take turns of shift – filling the barrels that are usually made of local French pedunculate or common oak.

It is in the barrel that the tannins will develop, creating that golden caramel colour associated with Armagnac.

The cooper will make a barrel (400litres) from the same tree. The strength of grain will depend upon where the wood is sourced within that tree, and all the wood is local keeping in line with the tradition and provenance. If a rougher grain is employed initially (often for the first two to three years) the tannin yield is high giving colour and taste; the liquid will then be transferred to a ‘smooth’ barrel to continue maturing.

This process takes years.

The barrels are plugged with a cloth around the cork to allow oxidisation. There is an atmospheric loss over the years, which is commonly known as the ‘angels share’. When the desired maturity is reached the Armagnac is then moved to large glass containers colloquially know as ‘bonbonnes’.

From this point on there is no change in flavour so often a house will only bottle an older vintage on request. This allows flexibility for blending with other vintages if desired.

When it comes to vintages they do not correlate with good wine harvests but are frequently priced because of volume/ availability. It is important to understand that given all these variables each house has its own style, character and taste and colour. This is why top end suppliers, collectors and sommeliers flock to this region for their supplies.

And, unlike whisky, vintage Armagnac is comparatively good value. A bottle of Domaine De Bellair 1967 from Darroze will cost you £235 an equivalent quality of whisky might cost in the region of £2000 – £3000.

It’s also important to understand the personality behind this remarkable drink, produced in some cases for centuries on the same land by the same families. Each and every one has a story waiting to be discovered.

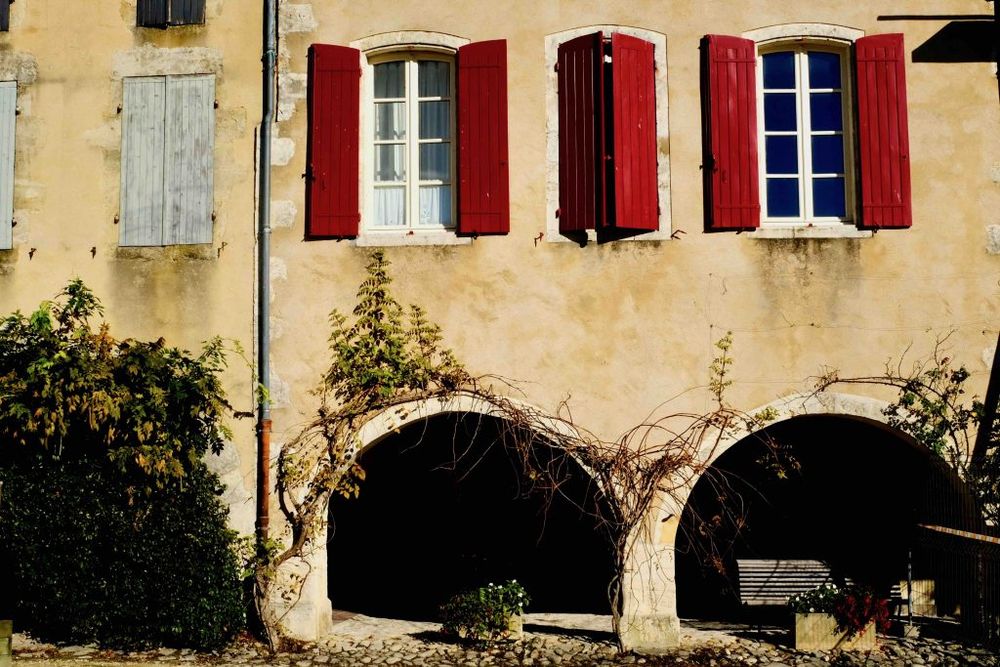

I called in on Florence Castarède, sixth generation and matriarch of Armagnac producers who have been making their brand since 1832. She lives in a grand château on the land that has the vines. Surrounded by old farm buildings, some of which have 17th century frescoes, the cellars date back to 16th century.

Her approach is simple… make the best Armagnac you can for the best price you can.

As the sun set I tried a few younger Armagnacs and then moved onto the 20 year old which had a smooth soft flavour with a great colour. “Would you like to try your year?” she said.

Puzzled at first I realised she meant my birth year, as it turns out 1964 is very good with a big depth and a very long finish.

The colour was rich with deep golden hues, even the empty glass had a tint of colour from the viscous content and just the slightest amber lingering.

This, of course, is a trick she has pulled before and knew how good it was.

I must have made the right noises as she smiled again and passed me something very special indeed. A 1924 from her house that, like her, had dignity, class and distinction with no ‘burn’ at all.

To really experience this esoteric world of high quality spirits – whether you’re in for a case or a bottle – is to go there yourself.

The rich fertile soil and warmth and passion of the people who make this unique (and versatile) drink that is not only popular with cigar-toting oligarchs but also with the bearded dudes of Dalston and their cocktail shakers, is well worth the journey. Find your special taste, or in my case year, and you’ll have a happy Christmas, guaranteed.

I stayed at this excellent guesthouse www.lesbruhasses.fr/en/ Here is some info about Armagnac and the region www.armagnac.fr and www.tourisme-gers.com/

Neil Hennessy-Vass is one of the UK’s leading food and drink photographers as well as having a particular liking for fine food and drink. See more of his work here