“I think freshness is the DNA of Champagne,” Lécaillon argues.

“We used to struggle for ripeness, now we fight for freshness.” This is how Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon encapsulated the current climatic situation in Champagne. Lécaillon is chef de cave of Champagne Louis Roederer, a consummate scientist, keen observer and possibly this region’s acutest mind. He gave a master class ahead of the fourth London New Wave Champagne event at 67 Pall Mall with the theme of ‘Fighting for Freshness in Champagne’. He spoke, refreshingly, without notes or a slide presentation. He had clear points to make, all born from experience and observation, all illustrated by a series of Louis Roederer Champagnes.

Tim Hall, instigator and organiser of the event, reminded everyone that Lécaillon was also the current president of the technical commission of the Comité Champagne (CIVC), just to drive home the point that this man had insights to impart.

Lécaillon started by stating how much Champagne had changed over the past 20-30 years. He emphasised that for him the expression “climate change” was too mild, that what was really happening was a “climate crisis.”

A lifetime of questioning, observing, trialling and refining: Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, 67 Pall Mall, London June 4, 2019

But rather than painting a bleak future, Lécaillon emphasised how this crisis meant a complete shift of emphasis. “It’s important to return to the soil and to craftmanship,” he said about this region – that more than any other in the world it turned the challenges and adversities of its northern climes into a virtue. Its grapes, grown under Atlantic influence on the 49th parallel benefitted from the additional alcohol imparted by a second fermentation, gained extra body from extended lees ageing and tamed their acidity with dosage.

For Lécaillon all the processes that were developed out of necessity now represent a way of “preserving what nature has given us. Each detail in Champagne winemaking is the art of reductive winemaking, designed to protect the identity of the wine.” Lécaillon remarked that in the 1960s, 70s and 80s the idea emerged that it is “good to pick unripe grapes” but that he had looked back further.

“In 1899 and 1900 Champagne grapes were picked with potential alcohol of 11% and a relatively low acidity of 5.5g/l” (expressed in sulphuric acid – that would be approx. 8g/l of tartaric acid – high for most wines but not for sparkling base wine) – “super high ripeness” in his words. “We are now back at ripeness, like we were in the past. When you have ripe grapes, you have to up your game when it comes to fighting for freshness. But it also opens up new fields.”

What is he saying there? Ripeness, now once again a given in his region, is nothing to be afraid of. But it shifts the focus. “I think freshness is the DNA of Champagne,” Lécaillon continued. “it is not acidity, it is more. Of course, acidity is part of freshness. It is precision, purity, length and is made of many, many pixels. Freshness combines precision of fruit, salinity, sapidity, length and elegance.”

Using his wines to demonstrate how freshness is achieved

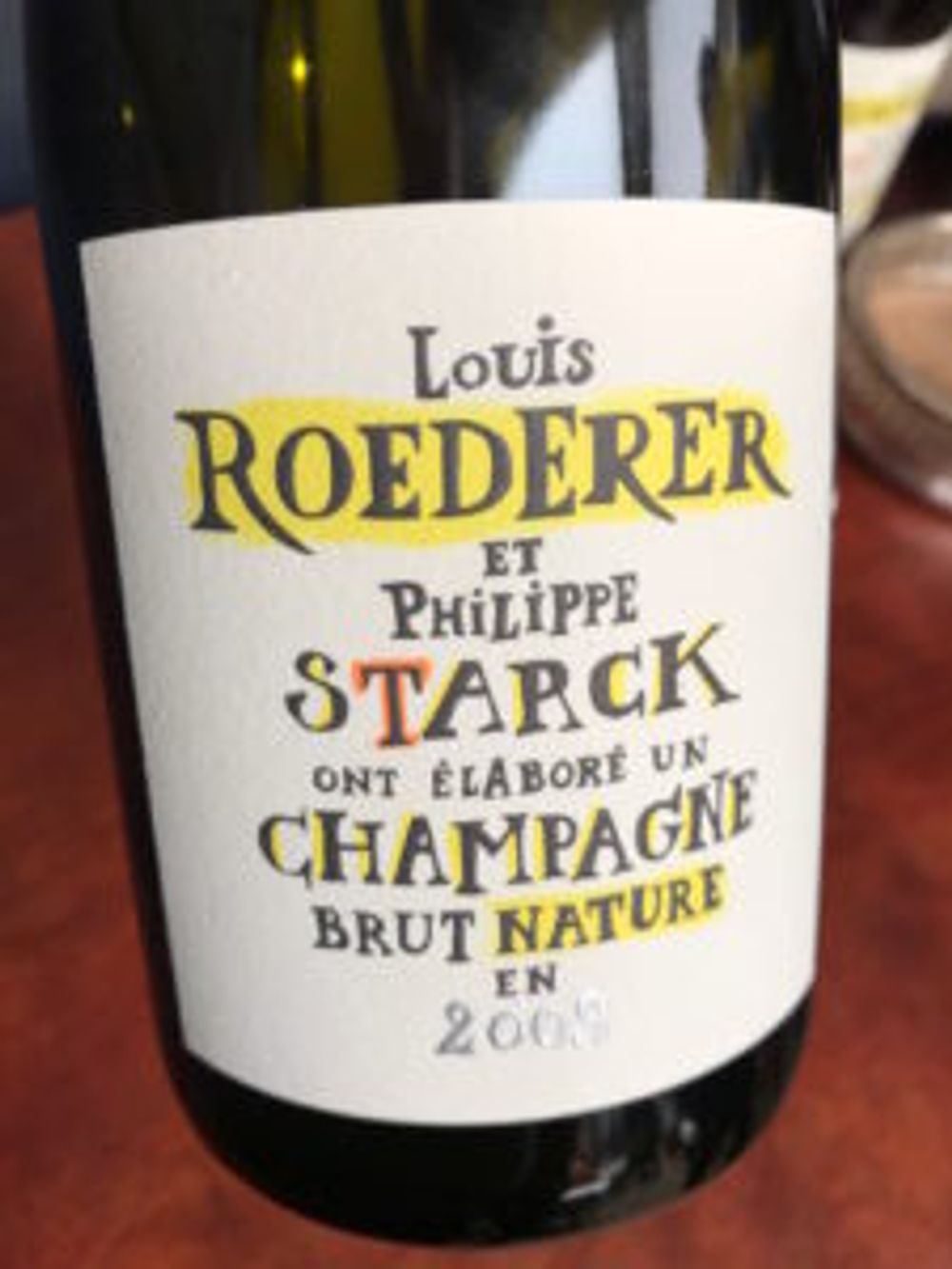

The first example was made by showing Louis Roederer Brut Nature 2009, only the second edition of this wine, made in a most unusual fashion. All the grapes for this wine were grown as a field blend of 21% Chardonnay, 52% Pinot Noir and 27% Pinot Meunier in a “deep, dark clay” as opposed to chalk, in the village of Cumières. The parcel is farmed biodynamically. The grapes were co-harvested, co-pressed and co-fermented. “We are only able to do this in very ripe, dry years like 2006, 2009 and 2012 [to be released later this year]. In this wine, designed from the start to become a zero-dosage wine, “we reinforce the reductive power of Chardonnay,” Lécaillon said. The grapes were picked very ripe, at between 11.6-11.7% potential ABV and the wines, with little sulphur addition, were partially aged in oak. Malolactic fermentation was not encouraged but if it happened it happened. At bottling the wine was also protected by jetting.

For a wine that was a decade old, it was incredibly fresh. The nose suggested mellow, ripe, golden apple with an edge of maple syrup spice, the palate, however, was a jolt of bristling, exciting freshness – certainly not for the faint of heart, but a lovely, lively, energetic expression of Champagne. Lécaillon thus demonstrated that a richer soil, a field blend and a warm dry year could present a vivid balance without the need for dosage that nonetheless delivers utter freshness.

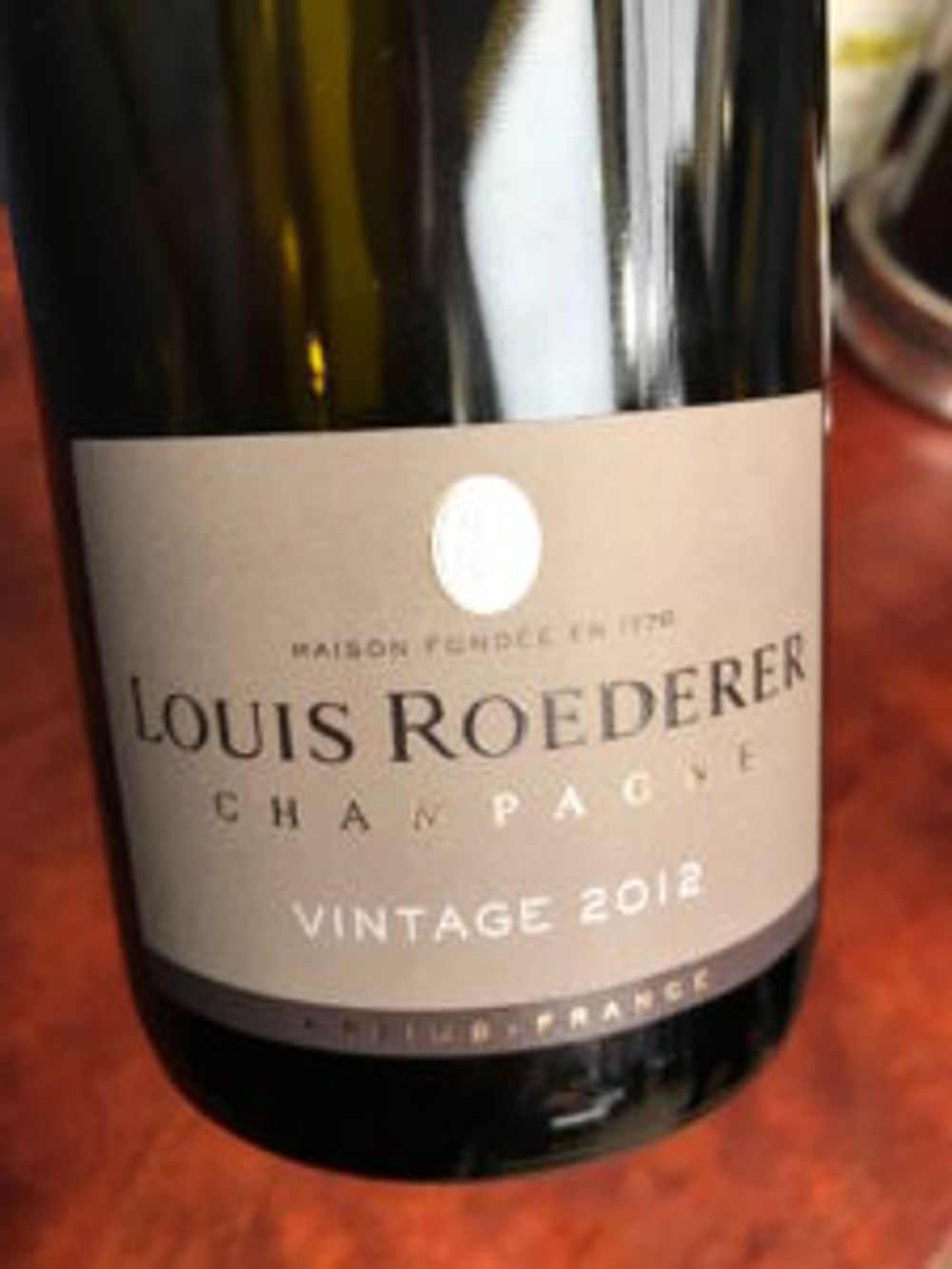

The next example was Louis Roederer Brut Vintage 2012, disgorged about one and a half years ago. Lécaillon emphasised that this now was all sourced from chalk soils: 70-80% of the blend was from two Pinot Noir parcels in Verzy that had been the first vineyards bought by Roederer in 1841. 20-30% were from an east-facing Chardonnay plot in Chouilly. “The Pinot Noir from here is very austere, almost too fresh, so we use this Chardonnay to add a smile to this austere wine,” Lécaillon explained. “Fighting for freshness is also about balancing freshness.” The wine was as straight as an arrow, utterly slender and of a supremely fine texture. Lécaillon himself described it as “powerful, intense, energetic and very, very classic.”

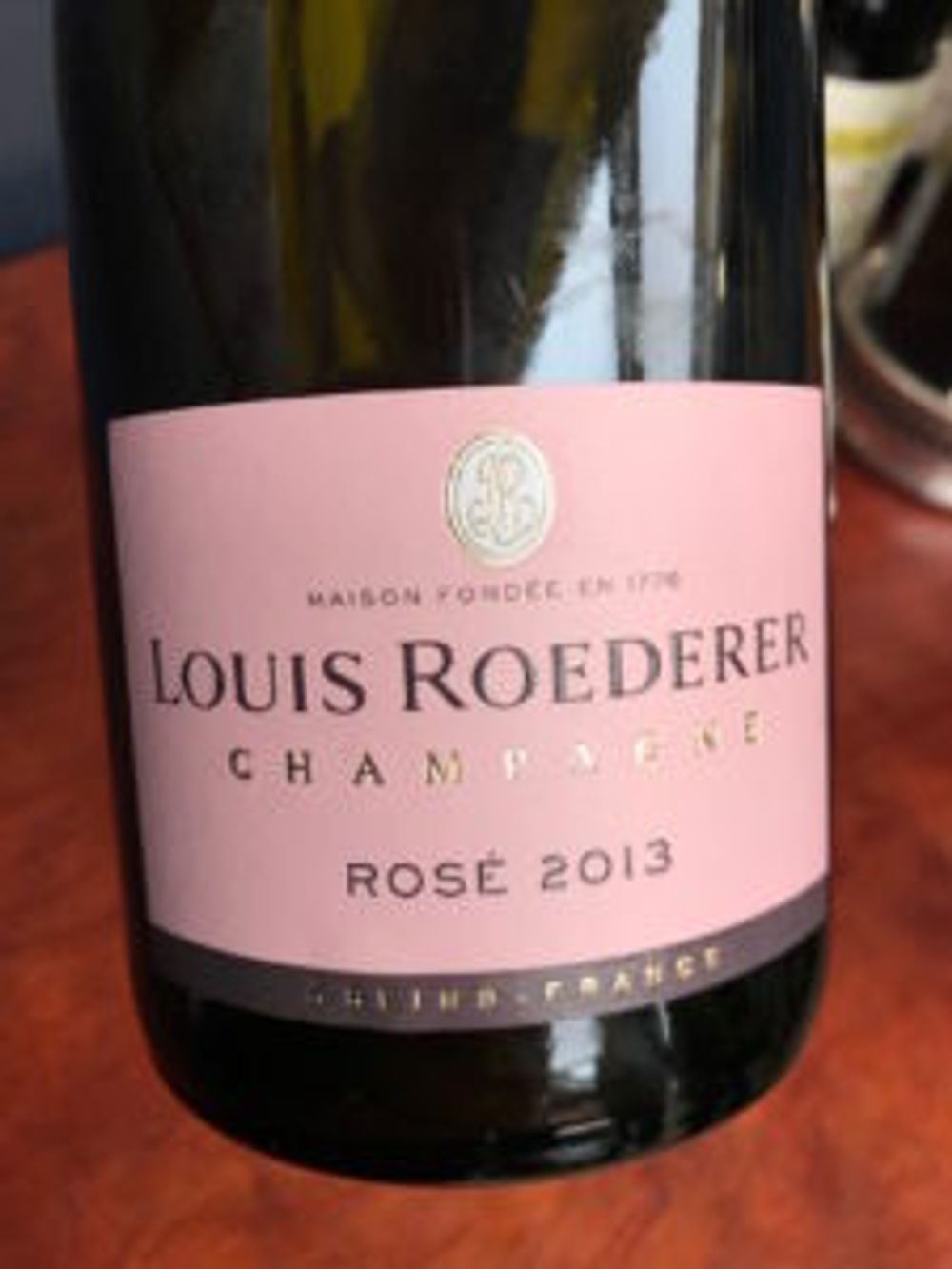

Next up was Louis Roederer Rosé 2013, this time with 60-70% of fruit sourced from south-facing Pinot Noir vineyards in Cumières which “needed the freshness” imparted by a north-facing parcel of Chardonnay in Chouilly. The technique of extracting colour for this rosé was the one developed in 1974 for the first Cristal Rosé that was ever made: the Pinot Noir grapes were harvested at good ripeness of 11.5-11.7% potential ABV, sometimes even 12%, de-stemmed but not crushed, and kept for 8-10 days under a blanket of carbon dioxide for a cold soak. Nothing was done to extract, no pigeage, no remontage. “it’s like tea, it’s just an infusion,” Lécaillon said. The moment the first stirrings of spontaneous fermentation began the wine was pressed, Chardonnay juice was added “and started fermenting as a rosé wine.”

The aim here was to get “velvety, silky roundedness of tannins and the freshness and salinity of Chardonnay from chalk. It is easier now to grow grapes and to ripen them,” Lécaillon said. “Up to now it is a great thing for us.” He described the viticulture for the Rosé-destined Pinot Noir as very akin to that of the Côte de Nuits – with yield calculated per vine rather than by hectare for very densely planted plots of between 10,000 up to 12,000 vines/ha. “When you make rosé, you have to adapt your pruning, your farming, your canopy. Everything has to be adapted to the kind of wine you want to make.” The wine, with its redcurrant and pink grapefruit perfume, was exuberant in its expression of both fruit and freshness.

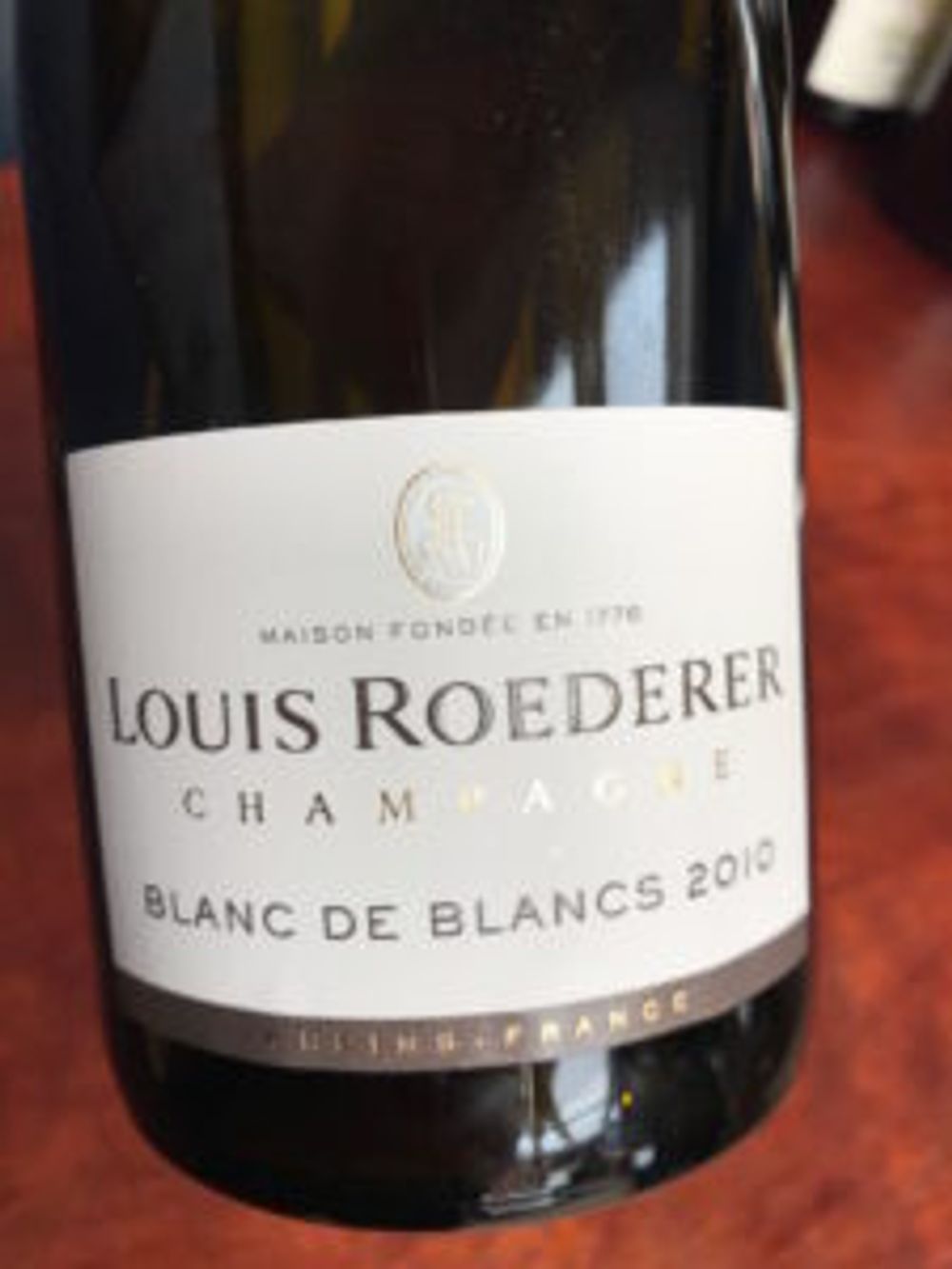

The next wine, Louis Roederer Blanc de Blancs 2010 then illustrated the power of pure chalk. Its water retention and low, slow mineralisation of nutrients ensures fruit of immense freshness. The grapes grew in Avize, two in the centre, one on the border of Oger, another on the border with Cramant. The grapes are picked at a potential ABV of 12% and no sulphur is added to the juice at all. This helps to oxidise everything that wants to oxidise and therefore stabilises the wine. “It gets rid of the fruit and just preserves the chalkiness.”

The wine was partly fermented in wood, malolactic fermentation was avoided and it was bottled with less pressure, just four atmospheres. According to Lécaillon full pressure with this kind of steely wine would be too aggressive. In fact, it was a statuesque, graceful, profound and slender beauty of utter creaminess and balance with real backbone.

The last wine, Cristal 2008 – which has already rounded out beautifully since its release last summer – demonstrated the power of old vines and their deep roots. The average vine age for Cristal 2008 is 45 years with the oldest vines 65 years old and the youngest 21. “There only is about 40-60cm of topsoil and the roots are deeply in the chalk, a moist and super-fresh environment. Having these deep-rooted vines means we can get reasonable [i.e. naturally moderate] yields with concentrated aromas and concentrated organic acids,” Lécaillon said, who then went on to describe the wine as “the Cristal of Cristals” with all the elements he wants: “elegance, finesse, length, lightness, salinity and something difficult to catch. I could drink hectolitres of it.”

As the master class proceeded the wines took centre stage. A near silence fell as Cristal 2008 was poured. But Lécaillon had made his point: he presented five wines of utter freshness that had all been harvested at fuller ripeness than ‘conventional’ wisdom suggests for Champagne base wines.

Lécaillon dreaming of a permaculture

Of course, there is far more to this – farming, above all, where Lécaillon is still pioneering, testing, questioning and researching so much. For 20 years already he has compared organic to biodynamic methods, and is still observing, refusing to draw easy conclusions – and admitting that there are things he might not understand but which quite evidently work in the vineyard. In fact, he admitted that he dreams of a Champenois permaculture.

Soil with all its properties, secrets and possibilities is at the core of Lécaillon’s work. Knowing and understanding this helps him to help his vines channel their ripening and to utilise the various practices of sparkling winemaking to bring out freshness – alongside ripeness. The wines he showed and which encapsulated his message in a mere two-hour slot are just the delicious tip of an iceberg: the advanced understanding accumulated during a lifetime of questioning, observing, trialling and refining.