“Aromatically quite restrained, the 2017 Garnacha oscillated between herbal and perfumed hedgerow fruit. The palate had added touches of savoury spice and currant fruit. Long-lived, bright, and elegant, the sort of wine you want to return to time and time again,” writes McCleery.

I am the daughter of a civil engineer. The underpass, roundabout, and bridge-building type. I am ashamed to admit that as a very small person, his world – from the materials to the trade journals – completely failed to capture my imagination.

My world was brightened by foodie smells, lushly illustrated novels, and Roald Dahl. It seemed unlikely our professional interests would every collide. Until now.

Winemakers Rosana Lisa and Alberto Saldón, London, November 2021

The Lalomba team has been back in London, presenting new vintages and ‘yet to be discovered bottles’ of these unique, single-vineyard Rioja wines. A rare and special treat.

Peter Dean gave us a detailed view of Lalomba – Ramón Bilbao’s single vineyard project – at the end of last summer and I won’t repeat the lowdown. Nope, I’m surprising myself (and perhaps Dad too) by shining the spotlight on concrete, the material that “underpins the winemaking” at Lalomba.

Winemakers Rosana Lisa and Alberto Saldón ooze passion for their work. Their presentation reiterates the extensive research that the Lalomba crew has undertaken, from UV analysis to precision viticulture. But it is the ‘teeth’ concrete fermentation vessels that capture my imagination.

Willy Wonka would have been proud. Striking, bold, unique in form and shiny-clean looking. I’m not sure I’ve seen something so beautiful made from concrete.

Rosana Lisa tells us that they opted for concrete after detailed research and experimentation, comparing stainless steel, oak and concrete. In the end they concluded, “concrete is the purest material … it doesn’t add any flavour or aromas to the wine, and it allows for excellent fruit character and expression with huge complexity because of the controlled micro-oxygenation.”

Concrete maintaining freshness

Lalomba covers four distinct vineyards stretched across Rioja. Finca Lalinde and Finca Ladero sit in the foothills of the Sierra de Yerga, whilst Finca Valhonta is planted on the slopes of Villalba de Rioja. Lastly, Finca Aguilones is perched on the banks of the River Ebro in San Asensio. Each unique, they have in common the much sought-after ‘cool climate’, and this further drives the choice to work with concrete.

Lisa explains: “Wines from cool climates or from vines planted at altitude have a very specific style because of acidity. Higher acidity makes wines with lighter body, and the tannins seem harder, with less-sweet mouthfeel. With this profile of wine, the management of material for winemaking is crucial in getting balanced wines… concrete is a perfect material for fresh wines. The micro-oxygenation from the porosity has a very positive effect on the palate. The resulting wines are softer with rounder tannins and with a juicier sensation.”

And who knew that not all concrete is created equal?! Just as a particular oak will be selected by winemakers for the tightness of the grain and the terroir in which the trees were grown, so too does concrete have a terroir story; the composition – the percentage of sand and the origin and size of the stones from which it is derived – all play a part.

The Lalomba team tested concrete from France and Italy and eventually settled on an Italian supplier whose concrete comes from Fontaniva in the north of the country. It is a region “with many sources of water – including springs – which means the material is well-washed, meaning the particles are smaller, adding rusticity and consistency to the material, which is very important for the tanks and their ultimate longevity.”

Winemakers Rosana Lisa and Alberto Saldón

Rosana Lisa goes on to explain that the presence of elements such as calcium and potassium will influence the final wine, “both can combine with tartrates and that will reduce the final concentration of acidity.”

And then comes the shape of the concrete vessels at Lalomba. These amorphous tanks are referred to by the team as the ‘teeth’ and they’re a sort of square-edged ‘tulip’, wider at the bottom than at the top. Unsurprisingly it is a shape that is unique to the Lalomba winery and was designed with délestage (rack and return) in mind. To cater for the characteristics of the fruit from each of vineyards, the winery houses 5,000kg-capacity ‘teeth’, all the way up to 11,000kg.

A further detail that marks Lalomba’s decision to work with raw concrete. Epoxy linings didn’t give the winemaking team the purity of flavour they were looking for. As is made clear, using raw concrete means that cleaning must be completed with painstaking attentiveness and using hot water is a ‘no no’ as the concrete could break.

I like that Rosana Lisa sees her work and that of the broader Lalomba team as being something of an “university” for the wider Ramón Bilbao group and for other winemakers across Spain and further afield. There would be something wasteful about keeping all their hard-won knowledge to themselves. She cites the use of concrete fermentation being embraced by colleagues in Rueda and with the Albariño grape in Galicia.

The marketing of the wines reflects the influence of concrete

So, what is the next chapter in this concrete?

Trials with malolactic fermentation in concrete, following vinification in barrel are well underway. The work they have done with Spanish universities in determining the concentration of oxygen in concrete versus oak has consolidated their view that, in some cases, malolactic fermentation in concrete is better for them than oak.

Oxygen concentration in concrete is typically half those found in oak, and this has a direct impact on the flavour and balance of the final wine. Rosana Lisa points out that when a wine is undergoing malolactic, it might already be 12, if not 16 months old and their job is to keep the fruit aromatics “at the top of the nose” and this is best achieved in concrete.

As fascinated as the concrete discussion is I am wary on two fronts. The Lalomba concrete journey sounds pricey, and I am also doubtful about concrete’s environmental credentials.

I am told that in the final analysis, the concrete tanks are only marginally more expensive than using oak and they believe that their potential longevity will ultimately offset this increased cost. When it comes to the environment, well … “concrete has a huge thermal inertia. It maintains temperature very well. This means that cool refrigeration during fermentation is not necessary… So, we have a big reduction in electricity consumption.” The design helps too with each tank consisting of two layers of concrete sandwiching a layer of water for temperature control.

All well and good but the time has come to get my head out of the concrete, so to speak, and into the glass.

How did the wines taste?

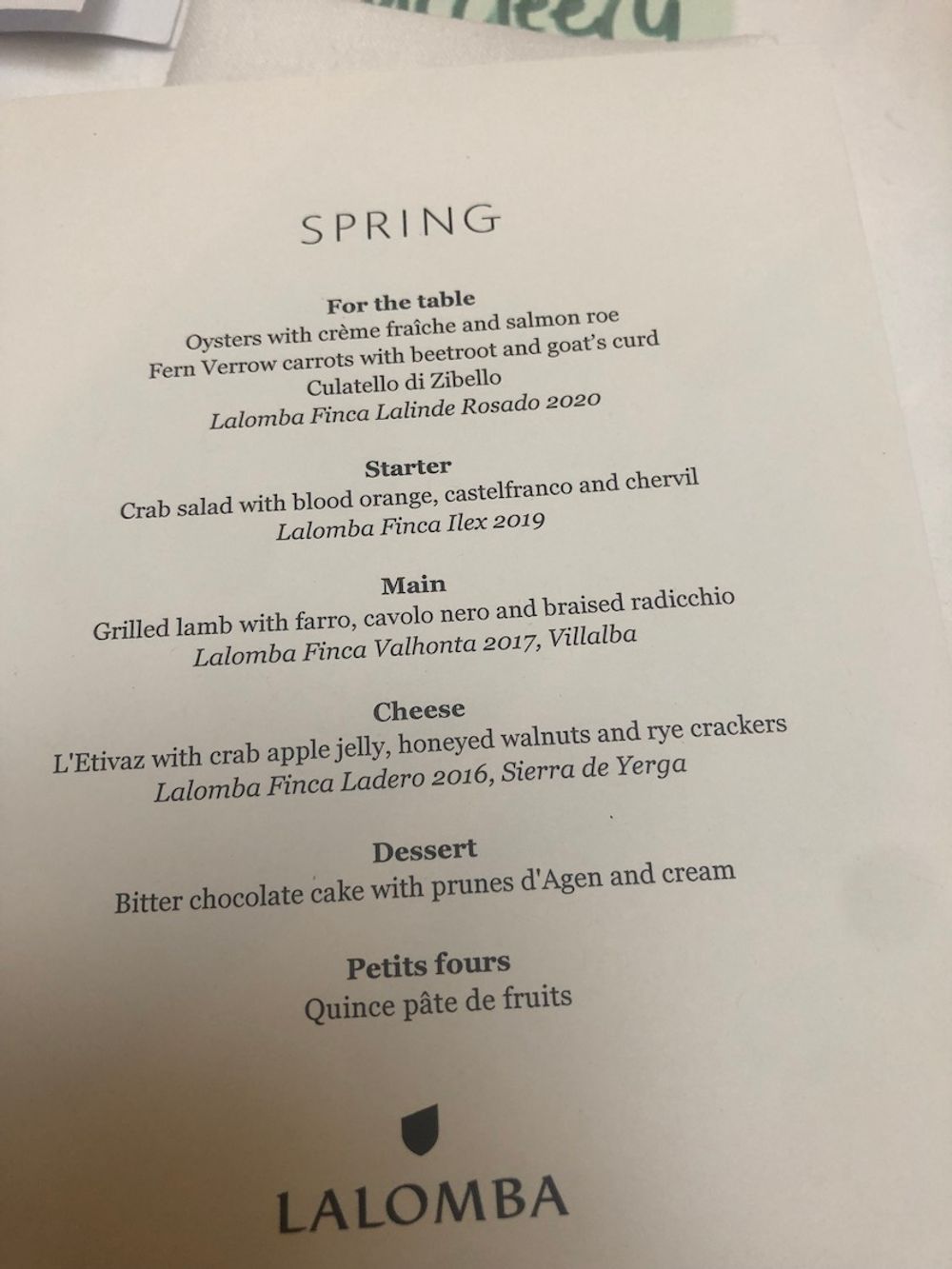

Lalomba tasting, Spring restaurant, London

We had the chance to taste two rosado wines. The first was the 2020 Finca Lalinde Rosado, Sierra de Yerga. Fermented exclusively in concrete, the palate has lovely volume and freshness and charmingly reminiscent of summer berry pudding. It has zing and a touch of peppery spice that add to the wine’s overall lively intensity. The 2018 Finca Lalinde Rosado, Villalba de Rioja was an altogether different animal, having been aged in 225-litre Hungarian, Querecus Petraea oak (grown at altitude), tailor-made barrels. I found the oak on this wine had just the very lightest of touch, but the palate was discernibly more concentrated; redcurrant and raspberry with meringue-like crunch. Hugely enjoyable from start to finish.

The four reds shown began with the 2017 Garnacha, Monte Yerga. Still in the tank this is a wine that appears to be enjoying its 44 month-long fermentation and ageing in concrete. In fact, we tasted a tank sample so it’s clearly at home for now. I hope they ‘let it out to play’ soon because it was the wine of the tasting for me. Aromatically quite restrained, oscillating between herbal and perfumed hedgerow fruit. The palate had added touches of savoury spice and currant fruit. Long-lived, bright, and elegant, the sort of wine you want to return to time and time again.

Next, we had a chance to compare the 2019 and 2017 Finca Valhonta from Villalba de Rioja. The 2019 was yet to be bottled but impressions at this stage suggest a wine with more immediate opulence than the 2017. That said, I like the upright acidity of the 2017 and the well-placed tannins made me think that it was going to be a treat of a glass to enjoy with food.

Sierra de Yerga is 100km, give or take, from Villalba de Rioja and here the six-hectare Ladero vineyard sits where the arid inland Mediterranean climate meats the fresher weather coming off the foothills of the Iberian mountains. The 2016 Finca Ladero appealed to my love for red wines that come with a bit of edge; rich, broad, smoky black fruits with dark chocolate and balsamic too, delivered with an impressive backbone of acidity and well-integrated, precisely articulated tannins.

We also tried the Finca Ilex 2019 alongside a crab salad that was a rare treat, coming for a tiny 1.3 hectare plot in Monte Yerga. Using 100% unoaked Garnacha, the nose was laden with black raspberry, dark chocolate and baking spices. Fermentation at cool temperatures – 50% with stems – and ageing on very fine lees, aiding the wine’s impressive sprightliness and elegance.

My Dad says that if you want to make tricky things appear easy you need to work ten times harder than anyone else. The wonderfully approachable and sheer drinkability of Lalomba’s wines is a great case in point… you could almost be fooled into thinking that their making had been effortless.

Dad was also right about concrete. Concrete rocks.

How the Lalomba wines were paired at the launch of the new vintages, Spring restaurant, London, November 2021