Germany’s oldest viticulture school is helping the wine industry future-proof itself against disease and climate change

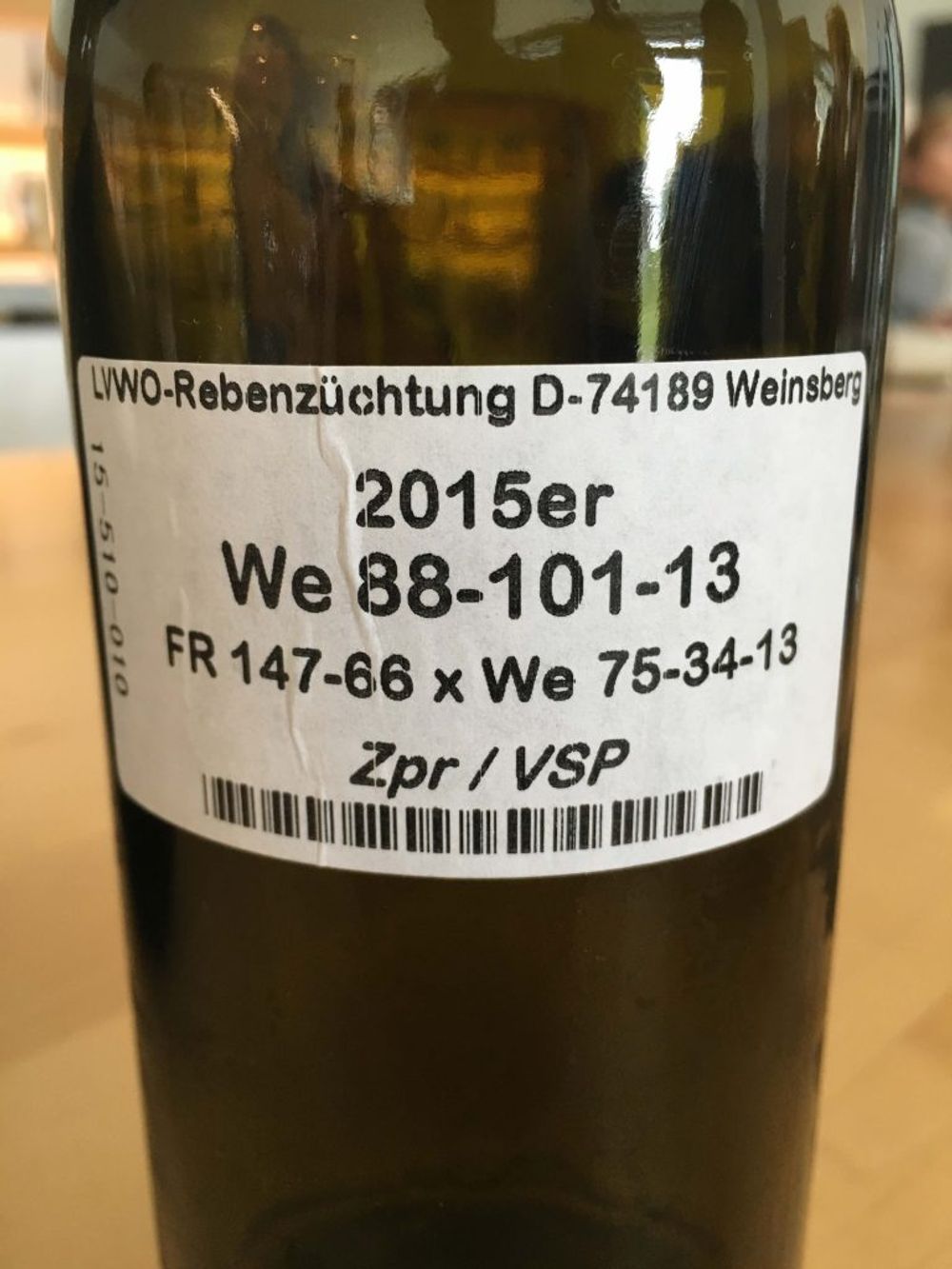

The German doctor hands me a small brown bottle with indecipherable markings. “Go on try this, drink.” ” What is it?” I ask, ever-so slightly apprehensively.

I am not quite sure I understand his reply. “The wine is from a new grape variety called We88-101-13. It is a cross-breeding of FR147-66 and We75-34-13.”

The wine is actually very good, Sauvignon Blanc-ish, but I honestly think they need to work on a snappier title.

“Does this wine have a name?” I ask. “No, have you got a good idea?”

Nice wine, shame about the label – the latest white wine to come out of the wine school

Welcome to the wonderful world of LVWO a viticulture school in Weinsberg, situated two hours South of Frankfurt in the state of Württemberg.

The oldest viticultural school in Germany, it has been educating people about viticulture and helping them market their wines through the Staatsweingut Weinsberg winery, since 1868. The viticulture school has been at the forefront of improvements in vine stock and wine quality for almost 150 years and has been a breeding ground for major advances in combatting vine disease, experimental cross-breeding, for re-discovering old grapes and wines and setting out the blueprint for what has become the modern revival in German winemaking.

It can also give pointers to other viticulture schools around the globe on how to prepare for and keep abreast of climate change.

“The main aim of the school is to give more wine education to the winemakers and cellar masters of the future. To make progress through innovation,” explains Dr Dietmar Rupp, a Director of Viticulture at the school.

Dr Dietmar Rupp, Director of Viticulture, Weinsberg

Because of its latitude the German wine industry has always had issues with disease and with the ripening of certain grapes. New varietals have been cross-bred at the viticulture school that have helped resist disease and a good deal of work is currently being done on combatting new climate-related threats like the Asian fruit fly, Drosophila Suzuki, a fly that loves wet summer conditions and as a result devastated many crops in 2014.

Climate change has also meant that varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah are starting to grow better in Germany and meet the growing demand for international-style cuvées.

The barrel room at viticulture school is full of magnificent barrels commemorating the men whose names were given to new cross-bred varietals

Cross-breeding is a large part of work they do here. Not just for disease-prevention but also to meet and feed changing consumer demand. The most popular rosé and sparkling wine of Württemberg both originated from this school.

Poets and scholars from Schwaben and Franken have given their names to new bred varietals that have originated in the school which include Dornfelder and Kerner, the most successful new bred varietal of the Twentieth Century. Kerner is a cross between Riesling and Trollinger (the popular red grape of Württemberg) while Dornfelder is a cross between Helfensteiner and Heroldrebe. Kerner was certified as a new variety in 1969 while Dornfelder received its certification in 1984.

In the barrel room, 250 litre barrels celebrate the men whose names have been given to these hybrids.

On other bariques there are a plethora of different wines containing experimental clones and blends of cross-bred varietals.

The influence of the viticulture school partly explains why the multitude of grape varieties in Germany are clones of clones. Visiting one winery, Weingut Singer in Korb, owner Barbara Singer needed a blackboard to explain her massive portfolio to me, drawing diagram after diagram. It was pretty taxing stuff, especially in a day that had its first welcome drink at 9am.

Back to viticulture school and in other rooms you find what you would get in any winery, except much of it in miniature – fermenting tanks that look like diving equipment and are stacked upon one another like the cells of a beehive.

There is also an analysis room, which changes colour at the touch of a button, to help the students play with the colour of their experiments. It’s uber hi-tech that, if it had a large map of the world at one end, could easily be the lair of a Bond villain.

Attached to the school is a large commercial winery, Staatsweingut Weinsberg, that allows viticulture students to market and sell their wine.

There was one I couldn’t help noticing that was arguably ‘trying to hard’ to be hip. In fact it would make the perfect wine for an English surfing team, if indeed such a thing existed.

Being serious, the influence of the viticulture school goes far and wide.

A large percentage of the winemakers I met on a tour of the Württemberg and Rheinhessen regions are former students and, by the standard of their wines, clearly benefitted greatly from the technology on hand. As graduates they continue to benefit from information exchange with the school, helping them cope not only with setting up their own wineries but with the increasing need to change and meet the demands of the future.