“Though numbers are falling, the UK is still the top importer of Vins Doux Naturel wines in value terms whilst we don’t even register in the top five countries, when it comes to the most important export market for Roussillon’s dry wines,” writes McCleery.

Tucked up against the Spanish border the Roussillon is French Catalan, evident in the food and language. Fruit and olive trees span the area and the cherries from here are particularly sought after. I am told the Élysée Palace gets the first pick of the cherry harvest, every year.

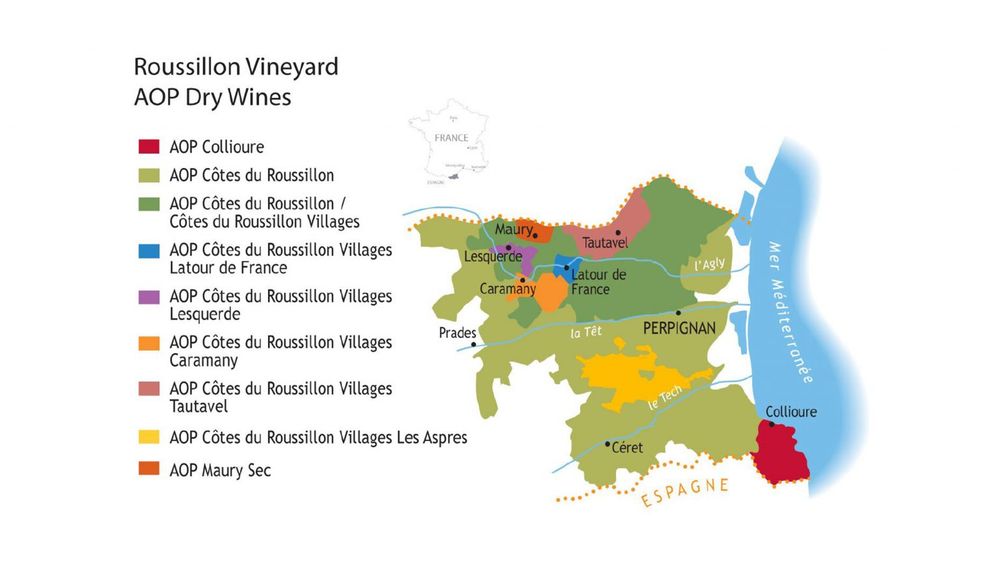

Vine roots run deep in Roussillon. They say that the Phoenicians brought vines here in 624 BC. Skipping carelessly by several thousand years of history, the region’s first AOPs were Rivesaltes, Banyuls and Maury in 1936 – all for fortified sweet wines. It would be almost 40 years before Collioure was the first dry wine accreditation. The creation of Côtes du Roussillon Villages came in 1977.

The 25 wine cooperatives dominate, representing three-quarters of production, but the 400 individual estates are steadily growing and increasingly influential.

Roussillon vineyards with the snow-capped Canigou in the background

Geography

There is a brief moment, flying out of Perpignan, when you get the bird’s eye view of the boundaries that define Roussillon in wine terms. The Pyrenees, with the snow-capped Mount Canigou, sit to the west, whilst the Corbières mountains run along the northern border. The Albères mountains and the Spanish border are the southern edge with, of course, the Mediterranean Sea to the east.

Like fork prongs, the three rivers – Agly, Têt and Tech – run from west to east, creating three valleys, each with its own individual array of terroirs and microclimates.

With an average of 316 days of sunshine a year, the sun-kissed Roussillon is nevertheless windswept by no less than eight named blustery winds. The cold, northerly Tramontane is undoubtedly the best known; vine growers visibly hunching their shoulders when they describe winter pruning in its chilly ferocity.

Rain falls minimally and often comes in a thunderous package, meaning much of the potentially beneficial water is lost in run off.

The wild terroir of the Agly Valley oscillates between granite schist and black marl surrounded by garrigue

Soils and Terroirs

The Roussillon today is the result of significant geological changes in the tertiary and quaternary periods and this comparatively small region is home to a complex range of soils.

In simple terms the Agly Valley is best known for its schistous soils, whilst the Aspres is associated with rocks and clay. Altogether different are the sea-facing terraced vineyards of Collioure and Banyuls.

One of the most impressive facts about the Roussillon wine region is that whilst permitted yields can be as high as 90 hectolitres per hectare, the region’s average is closer to 30 hl/ha. Several estates quoted yields of 10 to 15 hl/ha. Vine age plays a significant part in this, though the dry weather and soils are equally important factors.

Organic, Sustainable

Of the 18,932 hectares that the Roussillon currently has under vine, 29% has organic certification. What I cannot give you is the number of hectares that are signed up to alternative sustainability schemes. One of these days I will have the will to pull together a list of the many associations and certifying bodies whose logos are now stamped on wine labels and what they actually represent.

Visiting, as I did, in a rarely still time – weather wise – I was strongly aware of liberal sulphur spraying that tingled its way onto my tongue and into my eyes.

Then, of course, there’s the whole bottle weight minefield. Just once or twice, I felt an irritable twitch at the heft of certain wine bottles. We all know that the carbon footprint of shipping wine is woefully high, and I cannot reconcile the presence of an ecocert stamp on the back label of a bottle that might give me great biceps but do very little to help the environment.

That said, it is clear that the Roussillon’s warm, dry climate is well-suited to organic vine growing and well-established estates like Cazes are a terrific showcase for the region. We heard that Cazes will soon be the first vineyard in France to take delivery of a fully electric tractor. It was the price, not the sulphur, that caused the eyes to water. The inarguable benefit of a wealthy investor such as Advini.

Freedom. Liberté

Diversity of permitted grape varieties

For me, one of the most striking features about tasting in the Roussillon was the articulation of a good deal of freedom for winemakers in the region who can choose to make wines from 24 varietals across 14 AOPs and two IGP certifications.

Even at the potentially most restrictive, AOP Côtes du Roussillon Villages level there are five permitted varietals. Some producers noted a frustration that they were required to blend at least two varietals and that there are further constraints surrounding the proportion of Syrah and Mourvèdre that are allowed.

The majority of people I spoke to, however, were happy about shifting – if they hadn’t already done so – to the IGP Côtes Catalanes. Here, white, rosé and red wines are permitted and, if my maths is good, there are 11 permitted red grapes and 12 white varietals.

A well-travelled and curious collective of winemakers

Of those I met, the winemakers had spent productive stints visiting – and indeed, working at – estates all over the world. Argentina, China, USA (not just west coast, Virginia too!), South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Spain were all mentioned as having offered insight into winemaking techniques and the styles of wines they wanted to make when they returned home.

With no strong precedents in place, I saw pretty much every sort of fermentation and ageing vessel in a matter of days: amphorae (both terracotta and stone), new and old concrete, wooden barrels in all manner of sizes, stainless steel … Discussions suggested a strong culture of experimentation and a willingness to learn and evolve as experience builds.

Vins Doux Naturels – ditch the burden, embrace the possibilities

It is intentional that I have chosen to come to the Roussillon’s fortified sweet wines late on in this feature.

For many in the trade, Vins Doux Naturels (VDN) are the wines that first spring to mind when they hear Roussillon wine. True, the locals have been making the wines for an impressive eight centuries. This history, it seems to me, weighs heavily on the shoulders of today’s winemakers.

There is sincere and rightful pride in their sweet wines but there’s also appreciable gloom and frustration in the cellars when we are told they can be tricky to sell and often misunderstood. The speedy transition to dry wines in Roussillon seems to have left the local winemaking community conflicted in their communication – a lingering sense of betrayal that the wines that once brought fame and fortune to their home now need to share the spotlight.

If it were me, I’d stop talking about the history and how loved the wines were by preceding generations. The time has come to embrace them in the context of 21st century wine drinking.

As is customary on these trips, ideas – often seemingly ludicrous – spill forth somewhere between the hours of 10 and 11 o’clock at night. But perhaps www.roussillon.wine should consider hosting a VDN cocktail drinks party after its June tasting in London. There may actually be some mileage in a year-long tourist treasure hunt that encourages visitors to explore wineries and vineyards, a ‘golden ticket Vin Doux’, the winner’s prize and so on and so on.

The quality is outstanding, the value for money so good it’s almost embarrassing and there is diversity in the wines too, being white, rosé, amber and red too.

Latest figures suggest that Vins Doux Naturels represent just 18% of bottled wine in Roussillon today. Though numbers are falling, The UK is still the top importer of VDN wines in value terms whilst we don’t even register in the top five countries, when it comes to the most important export market for Roussillon’s dry wines.

The whites: fresher in style than anticipated

Communicating the importance of balance

I suspect that some people are going to pick up bottles of Roussillon red wines, take one look at the ABV and pop them straight back down again.

It’s not hard to understand why. There’s a trend for low-alcohol, fresher wine. How about we start a trend for ‘balanced wines’? More times than I care to admit on this trip, I was astonished to find I was sampling – and drinking (heck, yes) – red wines with 15.5% abv. Even I admit to steering clear when it’s a wine I don’t know. Happily, time and again, the wines were so fresh and so vivid, they were a pleasure to drink.

Strikingly, the whites were considerably fresher in style than I had anticipated. Winemakers are showing judicious skill when it comes to picking white grapes for dry wines, rather than for Vins Doux Naturels, in turn keeping ABV levels in sprightly check. Careful fermentation is also helping with this. In four days, there wasn’t a white that felt excessively high in alcohol. That’s an achievement! Thank goodness too for that chilly Tramontane wind.

We, in the trade, need to get better at talking about balance in the same way that we did with the wines of California through The Pursuit of Balance project that did wonders for the direction that those wines were headed in. If we don’t, wines like those of the Roussillon will not be enjoyed by as many as they should.

In Summary

I asked the representatives and winemakers of Roussillon “if you had only three adjectives to sum up the wines of Roussillon, what would they be?”

Here are the three that matched what I found: Surprising. Generous. Nascent.

The Wines of Roussillon trade and press tasting will take place in London on June 13. There will be two masterclasses focusing on red and white table wines. To register click here.