David Faure’s ambition for Château Mille Roses was to create a business that was “a bit more than just making money” which has meant not following Bordeaux’s traditional winemaking ways.

Change is afoot in the Médoc. A new generation of winemakers is making wine differently from the past, with the future in mind.

For David Faure, the turning point came with the birth of his first child. He began to consider the kind of legacy he wanted to leave for the next generation, and he was determined for it to be a healthy vineyard, and planet.

Faure has now been producing wine organically at his estate for 12 years and he is part of a new wave of young winemakers in the Médoc. This generation is doing things differently to the one that came before them. Producers are placing greater emphasis on sustainability, affordability and a style of wine that is more fruit-forward and approachable in its youth.

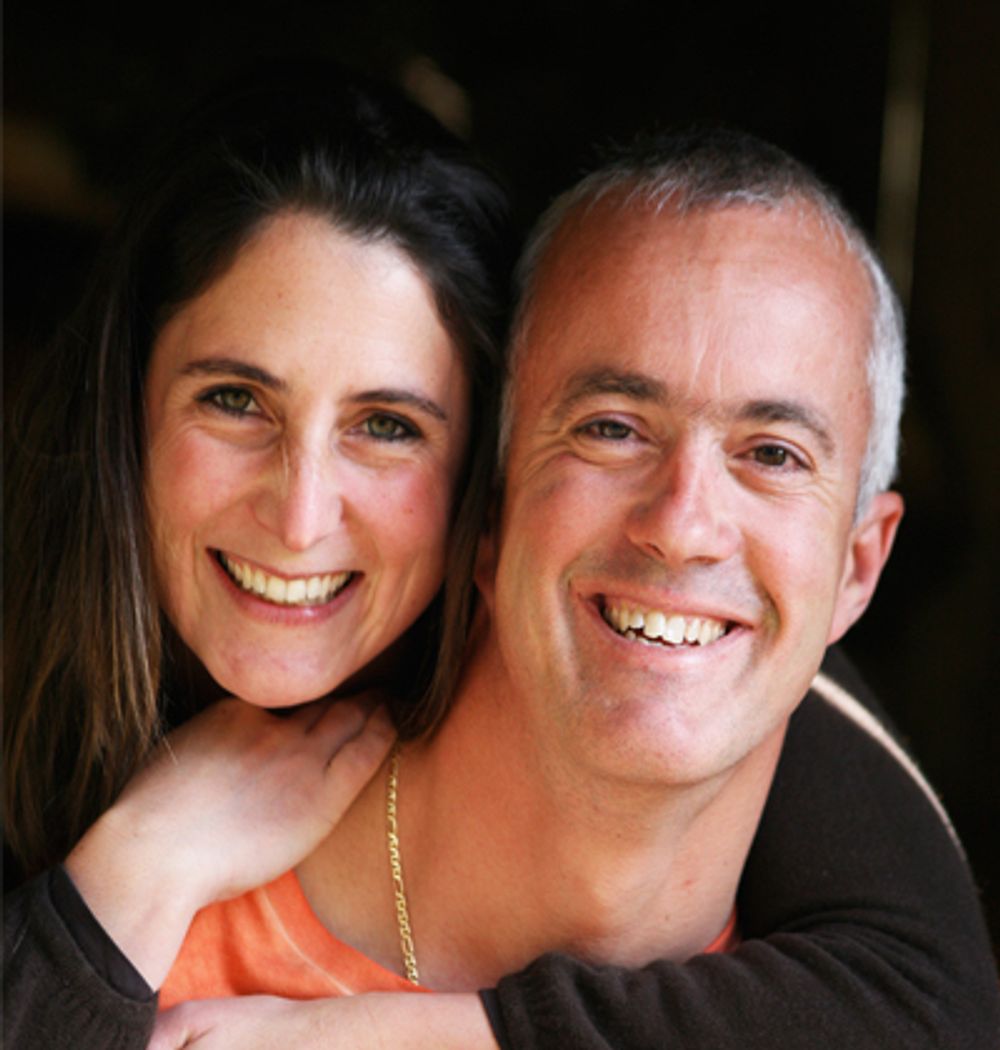

David and Sophie Faure want to create a healthy wine business they can leave to their children

When you take a look at the Château Mille Roses website, it seems like the organic-living dream. There are photographs of wild flowers, healthy vines and Faure and his wife Sophie’s three children helping in the vineyard. “This is a peaceful place,” says David, “and a beautiful place in which I hope my kids are happy.”

Building a future

I ask David if transitioning to organic production was partly about leaving a legacy for them?

“This was the beginning of building something,” David says. “Creating a company that transmits a bit more than just making money. To transmit a kind of good behaviour, to be concerned about what is happening when you work. They’re involved in the environment and so this behaviour is an inheritance. I hope that my son and my daughters will inherit this from me and will continue to improve it.”

Unlike his children, who are growing up in a vineyard and learning about wine by eating grapes fresh from the vine, Faure learned about viticulture and oenology at university. But the real education happened when he took over what is now the Château Mille Roses estate in 1999 and began to manage a vineyard for himself.

“This is when I really learned the profession – on the job. In the beginning, everything had to be done. We renovated the cellar and bought all the equipment necessary to produce wine. I also had to create my own label, as the house did not exist before 1999, and this was something I completely created in a commercial sense.”

As well as entirely restoring the property and building a wine brand from scratch (the name Mille Roses was chosen because his mother’s favourite flowers were roses), Faure also had to plant his vineyard. He only knew what he had been taught and for 11 years he did things in the conventional way.

Going organic has been key to Château Mille Roses’ success

“Initially I did not think for myself,” he says. “I found the lessons from school did not help me so much. It was mainly the other winegrowers who told me that I could do things in a different way. I knew that I had to change things, but I didn’t know how to do it. One of the neighbours closest to me had started the experience of converting to organic, so I just had a talk with him and followed his model.”

Faure emphasises the sense of community between the winegrowers at different estates. “We exchange ideas, but also materials and equipment. We take the time to help each other as we don’t have many people around us. We are connected when we talk about the job. We do the job in the same place, so we have the same weather conditions, the same questions about the weather, the rain. We have the same problems at the same time.”

Going organic

Château Mille Roses has some famous neighbours, namely Château Giscours and Château Cantemerle, both of which also farm organically. This is clearly a region of winning terroir. I ask if protecting the terroir is one of the reasons why Faure thinks organic farming is so important?

“Our place is well-situated just between two châteaux, that we know have very beautiful terroir. The terroir itself is special. It’s very important to me: to let the nature give what only she can give you alone. I don’t like the idea of working too hard in the winery. I think that the terroir is something you keep and by using too many things, manipulating the wine in too many ways, we risk losing our identity.”

Organic production is very much what the new generation of Bordeaux winemakers want to promote, says Faure

Faure believes organic production has helped to preserve the unique terroir-driven characteristics in the Château Mille Roses wines. The vines have to work harder and dig a little deeper; grape skins become thicker and roots become stronger. Many organic viticulturists say that this is where the grapes develop their complexity and character. There’s no doubt the vines and the land surrounding them are healthier, but has Faure seen an improvement in how the wines taste?

“We gain a few pounds of acidity every year on our wines, which is important for a well-balanced wine. The choice [to farm organically] was also something interesting for the taste of the wine itself, as the weather is becoming hotter, so you can gain a little bit of acidity from the way you cultivate your grapes.”

He recalls a time in France, around 10 to 20 years ago, when people thought that organic wines simply didn’t taste as good as conventional wines. It is still an attitude that Faure, and winemakers like him, have to contend with, especially in a region with such a strong legacy as Bordeaux. But attitudes are definitely evolving.

“Consumers understand something has changed,” he says. “The Médoc is still producing outstanding quality wines. They have good quality, just like they had before with the conventional way of making wine, it’s just that now they integrate the idea of the environment. This was not always the case 20 years ago.

“A lot of customers have asked if we are producing in an organic way and I think other winemakers will increasingly experience this pressure to change. Châteaux are having to answer more and more questions from their customers about their sustainability credentials, it is clear that this is a key influence on consumers and if, as a winemaker you’re not thinking in this way, I think there is a risk of getting left behind. This is going to lead to a complete change to the region in the next 10 to 15 years.”

Affordable pricing

Aside from organic production, there is also the topic of accessibility in the Médoc: many consumers still carry the perception that Bordeaux is expensive. The Médoc is home to eight famous appellations – Médoc, Haut-Médoc, Margaux, Listrac-Médoc, Moulis en Médoc, Saint-Julien, Pauillac and Saint-Estèphe – all producing magnificent wines which are sought after all around the world. How can the Médoc show everyday wine drinkers that wines from this region can also be more accessible in terms of price?

Faure hopes Bordeaux can find a better balance between its heritage and traditions and how it communicates to a wider audience

“People will discover Bordeaux again,” claims Faure. “Bordeaux is about 110,000 hectares of vines and there are just very few making the very expensive wines. Most of the wine produced in Bordeaux is great value and affordable. Consumers have a misconception of the Médoc because they see the ultra-premium chateaux and think that means the region is not for them. But this is not at all the case, really. Most of the growers make wine that is affordable, good quality and really exciting. The idea will change, just like people thought, at first, that the organic produce was not as good. It was completely false. No, no, it has to change.”

What does Faure think the next generation of winemakers in the Médoc will be like? Will organic wines become the norm? How about vegan wine? Will Bordeaux wines be less tannic, more easy-drinking – or could things go back to the traditional style?

“I hope we would not go in a direction in which we try to be just like others, for example, like the New World vineyards in Chile, Argentina, Australia, America. We have to keep our identity. In the Médoc, in Bordeaux, in France, wine is intrinsic to the culture. We have to present Médoc wine as part of the legacy of the region, wines that are hand crafted and artisan. Communication has to focus on the human story, the role of the winemaker and the terroir they’re working with. The future is bright for the Médoc but we must continue to present it through the lens of terroir, identity and tradition.”

The Wines

The Château Mille Roses main range

Château Mille Roses Margaux 2015

60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot 13% ABV

One swirl of this deeply-coloured Margaux releases aromas of plum, cassis, tobacco and cocoa. The delicate hand of the winemaking is evident on the palate: it’s structured and robust, but the tannins are smooth, contributing to the velvety texture. At six years old, the oak is already well-integrated and the overall experience is warming and rich. Available at Dulwich Vintners, £32

Château Mille Roses Haut-Médoc 2017

45% Cabernet Sauvignon, 35% Merlot, 20% Petit Verdot 13% ABV

This Haut-Médoc packs less of a punch than its Margaux sibling, but the fruit is fresh and vibrant, making for an approachable sip. Notes of blackcurrant and strawberry come through on the palate, alongside some savoury dried herbs and toasty oak. Available at Perfect Cellar, £31.45.

- To find out more about Château Mille Roses go to its website here.