Talk to winemakers the world over and their stories start and finish in the vineyards and wineries where they make their wine. Not in Lebanon. Making the wine is the easy bit. How they even get to plant vines, never mind build wineries and run successful businesses around the world is what singles this country out as a wine producing nation like no other.

Each and every producer in Lebanon has a story to tell that goes way beyond the wines they are able to bottle every year. For they are having to work in a country, and a part of the world, that seems to go from one crisis, and historical event to another where the threat of upheaval, danger of violence - like with the current Israel and Hamas war - is never too far away.

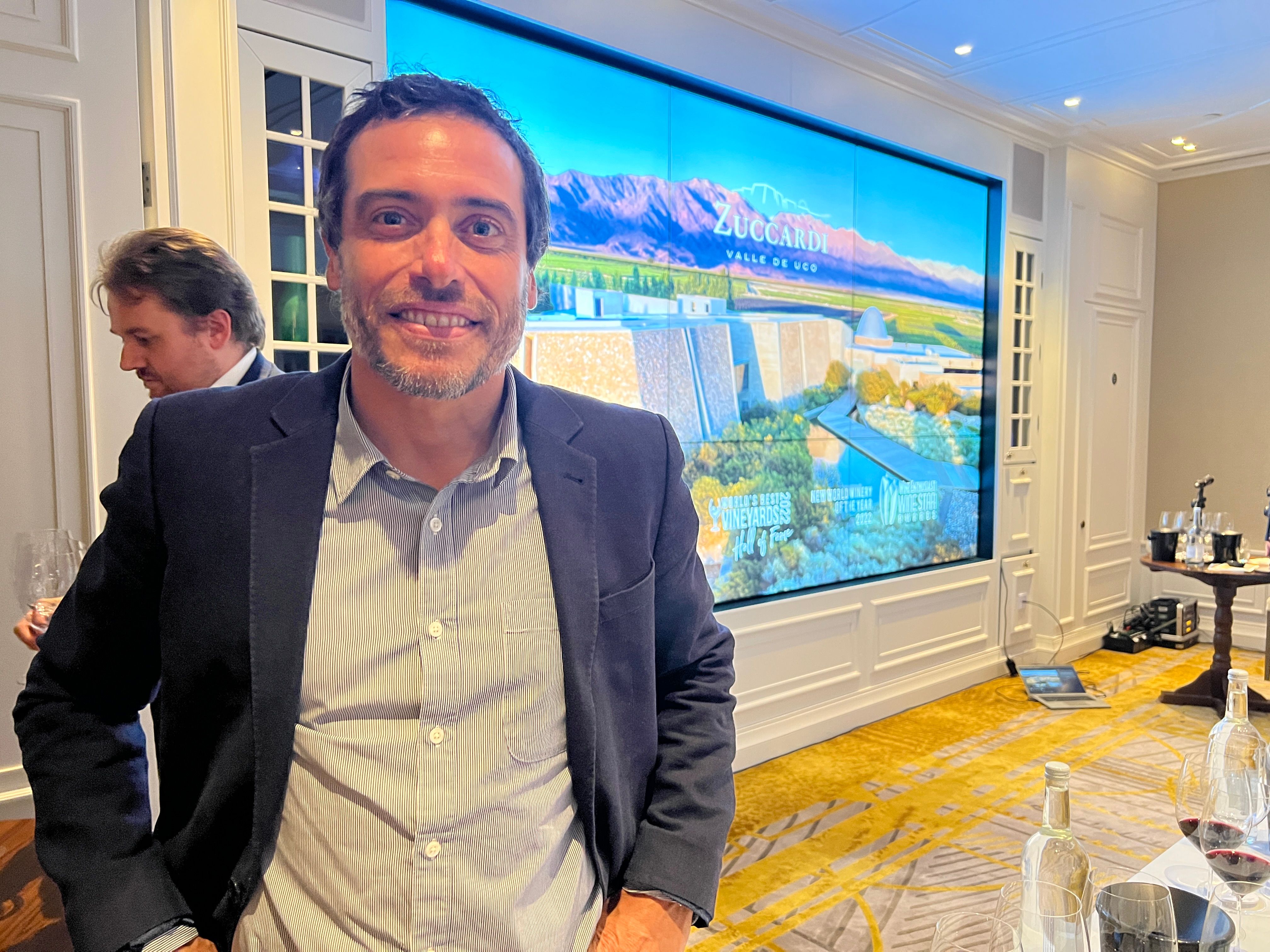

Sami Ghosn is proud to be making wine back on his family home in Lebanon.

But for Sami Ghosn this is what everyday life means for Lebanon and its people. It’s also why he did not think twice, on the back of the first Gulf War, about giving up a comfortable, well paid job and his Green Card in the United States to return, in the early 1990s, with a one-way ticket, to the country he was forced to leave as a young boy in the mid seventies at the start of the Lebanese Civil War.

Sami Ghosn speaks with some passion about sitting in Los Angeles and seeing what was happening in his home country and having an unshakeable need to go back.

A chance to go home and try and win back the family home and farm, situated in Tanaïl in the heart of Lebanese winemaking in the north of the Beqaa valley. Easier, though, said than done.The property had fallen into disrepair and become occupied by bedouins and it took Ghosn four months lying on its roof, with only a AK47 rifle for protection, before he could get get them to leave.

Going home

Sam, who was joined by his brother Ramzi in 1998 who also returned to Lebanon after spending time working in hospitality in France,now had the chance to reclaim their heritage and make a new family home and business together. It was what they had come back to Lebanon to do. “We had lots of happy memories growing up there with our parents and grandparents,” he recalls.

Initially they set out to make arak, Lebanon’s famous spirit, selling it out of their father’s pharmacy in a distinctive, eye-catching blue bottle. The Massaya name comes from twilight in Lebanese, which captures the moment the sun sets behind Mount Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley has been known to turn dark blue - hence the colour of their arak bottle.

The vineyards at Haddath Baalbek.

Their involvement in wine came as a result of a chance meeting with a French cork supplier who was looking to sell corks to Lebanese wine producers. Sami Goshn said he would buy some corks if he would introduce them to French wine producers looking to make wine in Lebanon.

Which is where the connection with their current French wine partners dates back to and an initial meeting with Dominique Herbert, formerly of Château Cheval Blanc, who saw the opportunity to make quality Lebanese wine.

“I brought in Dominique first, then Daniel and Frederic Brunier from Domaine du Vieux Télégraphe in Châteauneuf-du-Pape who met and became partners thanks to the founding of Massaya,” explains Ghosn.

It was their determination to make wine in Lebanon that gave the Ghosns the confidence to team together and start what he says was one of the first of a new generation of Lebanese winemakers and producers.

Which in the early 1990s only consisted of five other producers - Château Musar, Château Ksara, Kefraya, Domaine des Tourelles and Nakad.

Old and the new

The Massaya winery in the Beqaa Valley

Massaya now has two wineries. The first in the Beqaa Valley was joined in 2014 by its high altitude winery in Faqra on Mount Lebanon closer to Beirut. Situated 1,750 metres above sea level, at the foothills of the Mount Lebanon ski resorts, it overlooks Faqra, the highest altitude Roman temple in the world. Here it works with its white wines, and across the horizon it has views over the Mediterranean.

Its Beqaa Valley winery is now sourcing grapes from some of the more extreme areas of the region and up on the hillside slopes close to Syria, overlooking the famous Temple of Bacchus, in both Ras Baalbek and Hadath Baalbek.

Here it grows Grenache and Mourvèdre for its red wines, and Obeidi, Clairette, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Vermentino for the Massaya white.

This is where it now produces Cap Est, which comes from a seven hectare chalky site on the hillsides in the most north-easterly part of the Beqaa Valley at an altitude of 1,200m, in the Ras Baalbek area. A blend of 50% Grenache and 50% Mourvèdre and matured in oak for 22 months.

Thorman Hunt, its UK supplier, describes it as a “rare jewel that delivers both authenticity and great style. It is fantastic that this ancient wine region is once again producing a wine to rival the best in the world”.

Resistance winemaking

Ghosn describes the process of producing wine in Lebanon as “resistance winemaking” which is the same “way of life” now as it was for the Phoenicians five to six thousand years ago, always looking to trade, regardless of how difficult or dangerous the conditions are around you. As it says on its website: “Our ancestors and our land are our inspiration.”

“It is in our DNA to want to tell our stories and to trade,” he says, even if that does mean “risking your life in the Beqaa Valley” and going out to pick grapes and do a harvest with shells and artillery firing down on you from the Syrian hills. The “front line of farming” as Ghosn puts it - once having to send out trucks into the vineyards with Massaya banners on them to make sure they were not shot at during the Israel-Hezbollah war in 2006.

During the 2017 harvest the Ghosns were told by the Lebanese army to stop picking grapes in its Ras Baalbeck vineyards as it was involved in a military operation against ISIS there.

They now live in a country with over 2 million Syrian refugees, and the growing threat of the escalating war in Israel.

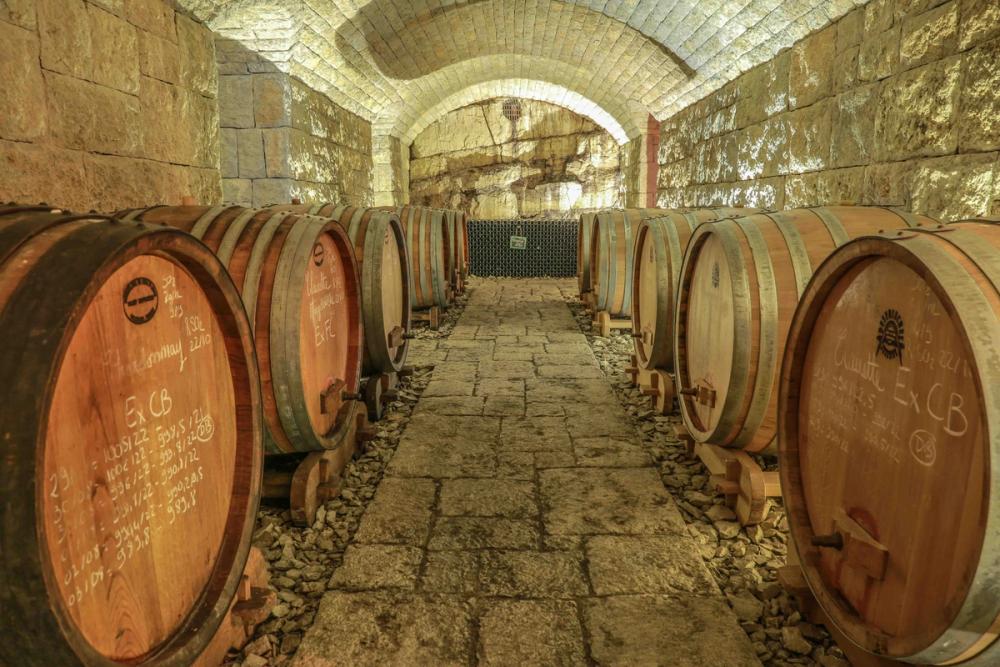

The cellars at Massaya

But you won’t find Ghosn, or any Lebanese wine producer, feeling sorry for themselves. If anything, working in adversity gives them the extra impetus and energy to find different ways of working.

“We want to shed the light on our culture and its importance to the world. We are ambassadors who have gone back to live in Lebanon to help tell its story, its heritage, its culture, its food and its wines ” he says.

It’s why all Lebanese producers share a kinship and sense of togetherness, he adds. “They are all on the frontier with us, they share the hardships with us.”

That need to be constantly telling its story to the world is why 80% of Massaya’s business is now overseas, in over 20 countries, and it is always looking to build up exports in key markets around the world.

It has also built a strong reputation for its wines. As Johnny Ray writes in the Spectator: “Where Musar led, Massaya folllowed in dramatic style.”

The UK, for example, is particularly important to Massaya and Lebanese wine in general, he stresses. It is why he works so closely with Thorman Hunt to build new premium on and off-trade contacts.

“I love looking for new opportunities. The UK is the country that put us on the map and we are so thankful to be here and selling our wines,” he says.

* You can find out more about Massaya at its website here.

* Its wines are distributed through Thorman Hunt in the UK.