"Most estates have maintained their 2022 release prices in 2023. A minority have been astute enough to reduce them." – Guy Seddon, Corney & Barrow's head of fine wine buying

Last year, I reported that smiles were back on the faces of growers, whose cellars were full of the generous and high-quality 2022 and 2023 vintages. A year on, what has changed? Aside from political turbulence in France and the prospect of US tariffs in 2025, Burgundy’s supply tap has been turned down dramatically. The 2024 crop ranged from small to barely there, hitting Côte de Nuits Pinot Noir the hardest.

The 2024 vintage is a story for next year but for now, growers have cashflow on their minds. With fine wine release prices at record highs, we have been in active discussions with our producers about the state of the market and our customers’ expectations. Having written to them in the autumn and followed up with conversations in person, we can assure you that the release prices in our forthcoming offers are the result of much scrutiny. We hope you will find cause to be optimistic. Before getting into that, let’s have a look at the season and the wines.

We tasted over three weeks, with one visit in early October and two in November. The 2023s were tasted from barrel, other than a few that had been bottled shortly before the 2024 harvest. We expected something similar to 2022, based on a general notion of summer warmth and an early harvest. The reality is more nuanced.

2023: another 2022?

In terms of character, it is very different. As for quality potential, the peaks are equally high – we came out of many a tasting beaming – but while 2022 was almost universally successful, the 2023 season threw more obstacles into the paths of producers. The ultimate success of each estate’s wines depends on how well they have navigated these challenges.

The first task was to moderate the huge potential crop through de-budding, green harvesting and – a new term to me – blue harvesting (cutting bunches at or following véraison – generally those which remained green). As Paul Chéron of Domaine du Couvent said, without crop thinning, they could easily have produced 60hl/ha. Domaine de l’Arlot’s final yield (pre-sorting) was 43hl/ha, the highest of the last decade.

Secondly, the hot two-week lead-in to harvest, with temperatures well into the 30s, made for a rapid accumulation of sugars, with malic acid going the other way. François Millet told us that temperatures of 32-34°C at harvest increased potential alcohols by 1.5% over 3-4 days. In these conditions, you had to be more precise than ever with picking dates. Varying ripeness from plot to plot required a patchwork approach – in the words of Domaine Leflaive’s Brice de La Morandière, “a week before the harvest we noticed that, depending on the plots, their load and their age, levels of ripeness were very disparate.” Alessandro Noli extended Clos de Tart’s harvest to eight days from the usual six, as “we took our time to cut only perfectly ripe bunches.”

Thirdly, it rained in the second week of September. This was welcomed by the later wave of pickers, such as Domaine Rossignol-Trapet (whose biodynamic viticulture has slowed the ripening cycle), who found that the rain contributed a further touch of freshness to the wines. Christophe Perrot-Minot says it helped turn the fruit profile from “black” to “red/blue”. As Adèle Matrot commented, the plentiful soil water reserves of 2023 explain why “it doesn’t feel like une année solaire.” Justin Girardin pointed out that the high crop load had itself helped to preserve acidity.

As for alcohol, 2023 is pleasingly moderate, coming in at an average of 13-13.5% abv after blending. Nadine Gublin at Domaine Jacques Prieur commented that their alcohols were 1% lower in the Côte de Nuits than the Côte de Beaune, as there was more rainfall in July in the former. While 2022’s heat-induced blockages of photosynthesis restrained alcohol levels (and allowed tartaric acidity to be retained), the modest alcohols of 2023 are due more to a steady supply of water in the soil.

For those who have navigated successfully, as our producers essentially have, the wines are more classically proportioned than the 2022s. With pHs on the higher side, there is an unexpected sensation of crisp brightness, aided by rich mineral expression and judicious use of stems.

Other vintages?

Distinctions with 2022 aside, a couple of vintage comparisons cropped up in our conversations during tastings. It is tempting to seek similarities with 2017 – another large crop, whose wines are classical rather than fruity. But the whites outperformed the reds in 2017, whereas 2023 is more evenly weighted.

At Puy de l’Ours however, Jean Orsoni called 2023 “the vintage of the decade for whites”, comparing the reds of 2019 to the whites of 2023 – both being fresh and precise, in a way people were not expecting (Jean qualified this with a reference to Puy de l’Ours’ higher-elevation plots, which retain freshness especially well).

Others drew comparisons with 2020, although mainly to illustrate how it differs from 2023. Alessandro Noli commented that in 2020 at Clos de Tart, there was very little juice in the grapes, whereas in 2023 there was plenty. As François Labet put it, “The 2023s have the flesh of 2020 but not the structure.”

Growing season essentials

Sweet Caress or sun’s anvil? With apologies (again) to William Boyd, let’s see if each month of the growing season can be summed up in no more than four terms. After a mild winter…

- March: fluctuating temperatures, frost-free, then warmer

- April: budburst, yo-yoing temperatures, green shoots, still no frost

- May: cool/rainy, spraying, bud-rubbing, successful flowering

- June: flowering finished, sunny/balmy days, cool nights

- July: heatwave, thunderstorms, green harvest, then cool/rainy

- August: rainy/unstable, véraison, then another heatwave, ‘blue’ harvest

- September: hot, sunny, rapid ripening, harvest

Harvest to sorting table to cellar

The harvest period was hot, with days beginning early (6am in the vines was not uncommon) and finishing by 2pm. Anne Morey described delivering bottled water to her pickers and hosing them down with a backpack water sprayer before inviting them to cool off in the domaine’s swimming pool.

Sarah and Guillaume Glantenay kept their cuverie at 12°C for grape reception. The last pick of each day was left in a cold chamber overnight to ensure the bunches were fresh for processing the following day. They said it was slightly surreal to have a vineyard team complaining about the heat while the cellar team were wrapped in fleeces.

The heat broke on 13th September, with a rainstorm. Following picking amid “crazy hot weather that was like July”, Jean Lupatelli was halfway through his post-harvest thank you speech to the Comte Georges de Vogüé team when the heavens opened, and they had to run for cover.

The next step was rigorous sorting. Christophe Perrot-Minot removed 10-15% of his crop on the sorting table, whilst Adèle and Elsa Matrot deselected a whopping 30% of their Pinot Noir. The full tool kit of vibrating, optical and density sorters can variously be found in today’s cellars (as might be expected, given the price of the wines).

Adèle also mentioned the “enormous” bunches of Pinot, the result of regular rain from April through to harvest – and, she believed, due to renewed vigour following the frost of 2021. Some of the Matrot bunches weighed 350g versus their normal 200g.

Even after highly selective sorting, the remaining crop was plentiful, for the second year running. Perrot-Minot made 33,000 bottles in 2022 and 40,000 in 2023, whilst De Vogüé and Domaine de Villaine produced slightly less in 2023 than in 2022.

Stems were ripe, enabling whole-bunch fermentation of Pinot Noir for those who favour this technique. Jean Lupatelli has once again used 50% whole bunches at De Vogüé, as have the Rossignol-Trapet brothers. By contrast, Nadine Gublin destemmed more in 2023 than 2022, due to some shrivelled berries following the heat of 13th/14th September. Logistics also had to be considered: although Géraldine Godot at Domaine de l’Arlot has entirely destemmed her Pinot Noir since 2021, she commented that the 2023 crop was so large, she wouldn’t have had enough tank space for whole bunches in any case.

I feel we may have reached ‘peak whole-bunch’ in Burgundy. As joyful as this method can be, there is a risk of its sappy, spicy character dominating the flavour profile in youth and obscuring terroir nuances, in a way not unlike excess oak or fruit ripeness. For example, Philippe Chéron and Christophe Perrot-Minot say they won’t go above 50% and 40% respectively while Édouard Labet of Château de la Tour/Domaine Pierre Labet stressed that the proportion of whole clusters is decided “plot by plot.”

During vinification, delicacy was once again the order of the day. The word ‘infusion’ has migrated from Bordeaux to Burgundy, for much the same reason – today’s drinker seeks finesse (and a slightly earlier drinking window). Anne Morey said that although white wine vinifications were “pleasant and easy” in both 2022 and 2023, Pinot Noir was harder to vinify in 2023, requiring more intervention.

Louis Trapet commented that malolactics went through quickly, due to the sun having killed off many yeasts from the grape skins. The low levels of malic acid will have helped, too. Malo at De Vogüé was finished by December, allowing racking in January and February.

The market

Or the elephant in the room. Coming hot on the heels of strong recent vintages such as 2022, 2020, 2019 and 2018, although our customers may not need to buy the 2023s, most really want to buy them. At the right price.

The higher echelons of the region’s wines are now ‘special occasion’ bottles for most. On the positive side, growers are aware of this, and that some release prices outstrip market values of comparable prior vintages. We have made this point to them at some length, both in the letter referred to above and in our conversations. There is a genuine desire among most producers that their wines are opened and enjoyed, rather than collected and traded. And yet…

There is seemingly inexorable pressure from the rising value of vineyard land, punitive inheritance taxes and bulk/négociant grape prices. It is now generally more expensive to produce a négociant bottling (from bought-in grapes) than one from domaine-owned vines, meaning that prices of the latter are raised to readdress the imbalance.

A general observation, beyond the C&B family of producers, is that some are unwilling to be seen to devalue their wines versus those of a neighbouring domaine. And if that neighbour happens to be a company with deep pockets, the tide keeps rising. Where have we seen this before? Oh yes, Bordeaux…

Most estates have maintained their 2022 release prices in 2023. A minority have been astute enough to reduce them. This should be applauded and seen as a sign of strength rather than an indication of an inferior vintage (which 2023 is not). I suspect that more would have come down were it not for the tiny 2024 waiting in the wings – but that is not the concern of our customers. The quality peaks of 2023 are excitingly high. My advice is to read the tasting notes, take advice from your C&B contact and, in the many places where quality and price align, buy with enthusiasm.

Tasting, ordering, drinking…

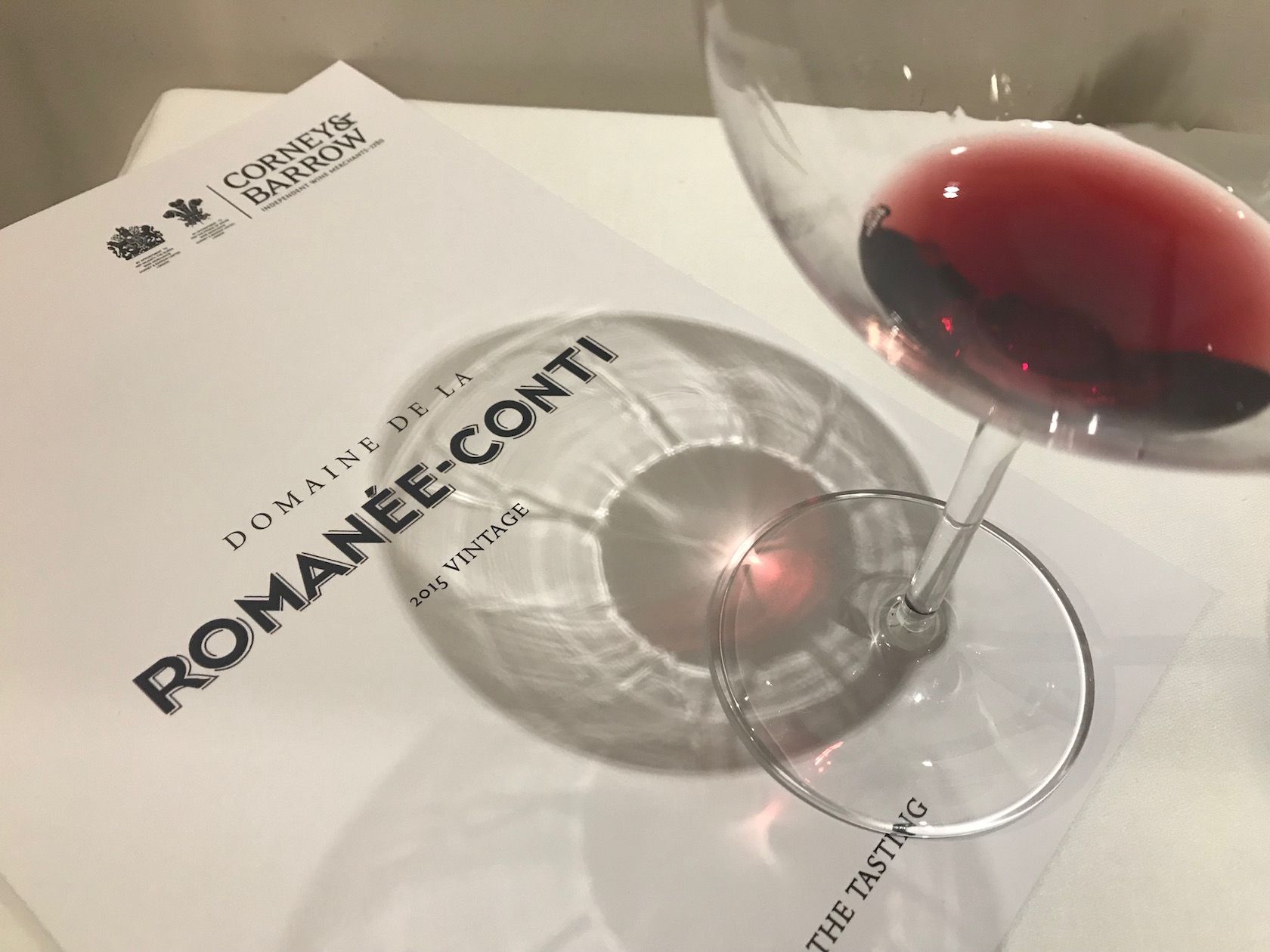

And so to our January en primeur tastings in London (14th), Edinburgh (15th), Hong Kong (21st) and Singapore (also 21st), which mark the start of C&B Burgundy season. The 2023s are a pleasure to taste – they are supple and balanced, making for an enjoyable experience. Please join us, in whichever venue you can.

Our tasting booklet will set out the wines available to taste on the day, followed by details of each C&B producer. All information, including our own tasting notes and prices, will be available online ahead of the tastings, at corneyandbarrow.com/burgundy-en-primeur.

Bonne dégustation !

Corney & Barrow is a commercial partner of The Buyer. To discover more about them click here.