Terroir-specificity has always been key to winemaking culture in Central-Loire but never before has it been used so knowingly by a new generation of younger winemakers.

A view of Les Monts Damnés, one of the key hills in Sancerre, seen from the new winery in Chavignol owned by Familles Bourgeois

If you want to know where Central-Loire is, put a pin in the centre of a map of France and there you pretty much have it – a region of seven disparate appellations that are linked to the Loire but also sees itself as pretty independent from the rest of the Loire.

Edouard Mogentti, main manager of the AOC’s governing body the BIVC, says that he thinks this is one of the key drivers of the region – to get people to understand that this is not the Loire proper, but a region with a separate identity based on its terroir and the wines that it is capable of producing.

Over several days I visited all of the appellations to find out more.

Finally a great vintage in 2018

There’s nothing like visiting a wine region after it has had a great vintage, especially if it breaks the back of a succession of miserable harvests. With wines in the tank and barrel, there’s a palpable sense of relief in the air as winemakers eagerly get you to taste fresh, cloudy wine samples that give an unadulterated snapshot of the harvest and how the wines will develop.

Sophie Landrat-Guyollot is the tenth generation vigneron and owner of this domaine in Pouilly-sur-Loire and the third woman in a row. “”It used to be more unusual for women vignerons/ owners here but it is getting more usual. It started when my grandmother started looking after the vines in World War 2 as my grandfather was a prisoner of war for five years.” Sophie is also part of Dames de Coeur de Loire, an organization comprising 30 women oenologists – useful for sharing problems and finding qualified employees, especially important with sustainable agriculture.

To get a sense of how bad Central Loire had it, Vignobles Berthier on the outskirts of Sancerre lost 90% of its 30 hectares to frost in 2016, then 50% in 2017. “In 2018 we have wine in the tank, but we still need wine in 2019.” Clement Berthier says, adding that he had to buy roughly 25% of his grapes externally in these bad years and considered buying fruit from outside the Loire just so he didn’t lose his positions in the on-trade.

Although his father made good wine, the move at Vignobles Berthier under his son Clement’s direction is to practise organic farming, use indigenous yeast and focus on terroir selection – vinifying each plot separately and making a real virtue of the soil, right down to portraying that on the bottles. Roughly 30% of winemakers in Sancerre are young, these days, according to Clement Berthier who says that many are turning to organic and marketing wines around site selection.

Berthier’s struggles in Sancerre are typical of the region as a whole and echoed by other winemakers throughout our tour of Central Loire and its six other appellations – Quincy, Reuilly, Pouilly Fumé, Coteaux du Giennois, Chateaumeillant and Menetou-Salon.

Anne Clément is the 15th generation winemaker at Domaine Isabelle et Pierre Clément in Menetou-Salon, for her the biggest challenge apart from frost (in 2016 they lost 95% of their crop) is the name of the appellation “In France people know it but abroad it’s not well known and hard to pronounce. In the US Sancerre is a brand and sells itself – people don’t even look at the name of the winemaker.”

2018, however, is an early, sun-driven vintage with the wines showing off the ripening of the summer heat waves, but also retaining great freshness and elegance. Most winemakers were getting maximum permissible yields of 65 hectolitres per hectare where many were lucky to get half of that in the preceding two vintages.

Domaine Vincent Siret-Courtaud is making wine in Quincy and Chateaumeillant but its base in Quincy is part of an association called Chai Maison Blanche, that is 14 producers working together and sharing tools and facilities, aided by French and EU agricultural grants. This has allowed them to buy 60 windmills (at a cost of €40k each) that means that 90% of their 120 hectares in Quincy and 90 hectares in Chateaumeillant are protected from frost.

Talking terroir

It is impossible to go to Central-Loire or indeed Chablis (which is just 70 miles away) and not talk terroir – soil is their religion and its various types manifest themselves in the names of the wines and on the labels. It is the very reason that fine wines hail from here in the first place and from the Southern Champagne region which are all part of the same Kimmeridgian chain – chalky marl soil interspersed with other layers of hard Portlandian limestone rife with fossils.

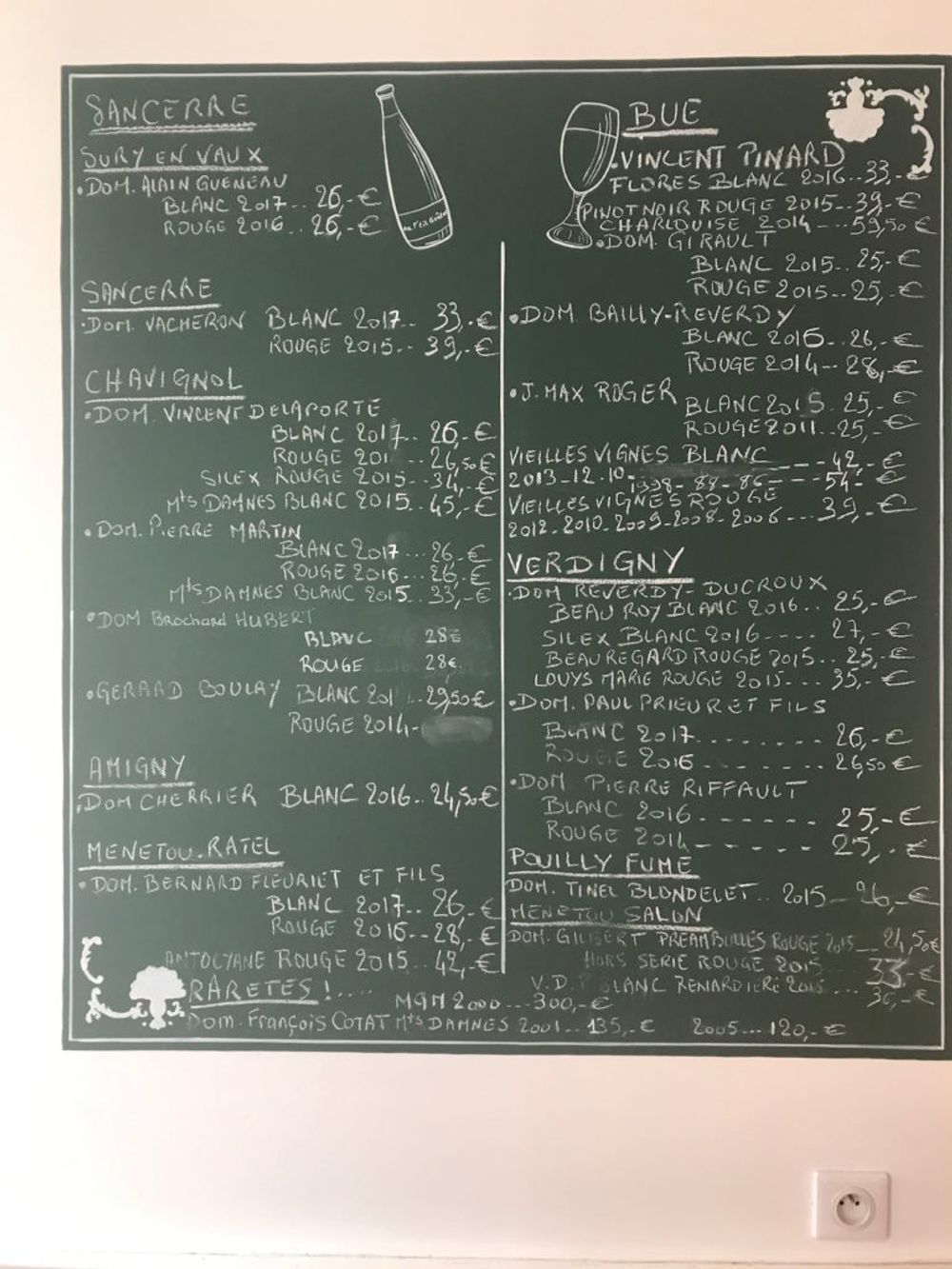

François Cotat whose wines are some of the most highly regarded and revered in Sancerre, are now strictly allocation only. The UK is Cotat’s most important export market as it is here that his international reputation was first forged. François is a notoriously shy man who likes to let his wines do the talking which is why you will not see him in any photographs.

Throw some ancient seismic activity into the mix and the effect of the resulting major rivers and you get other bands of soils exposed – sands, clays and gravels. So Sancerre, for example, which lies on top of a fault ridge has two major types of soil either side of its steep hilly position which is different from the soils on the Pouilly side of the river. With Sauvignon Blanc, of course, a grape variety that expresses its terroir so transparently, the difference in the soil type is there in the glass. The smoky gun flint style from the silex (flint) soils around Pouilly-sur-Loire being a classic example and Didier Dageaneau’s Silex cuvée arguably the apotheosis.

Terroir-specificity is key to the wines of Sancerre, Pouilly-sur-Loire and Menetou-Salon, but this focus on terroir and marketing the wines as such is now moving out to the other appellations of Central-Loire – in particular Coteaux du Giennois and Reuilly.

The notion of terroir has always been there, of course, but it is only in more recent years that winemakers in these other appellations are using it to vinify separate plots, make it central to their winemaking and their marketing – which has been a key tool in breaking into the premium end of international markets, and not relying on the domestic market which has been dwindling.

With the French drinking less and an increase in international consumption, Famille Bourgeois has turned its attentions to export. A new winery built at Chavignol between 2000-2004 has seen the estate’s capacity rise to 1.5 million bottles per annum and exports increase from 45% to 65%. From two hectares in 1936 the family now owns 66 hectares in Sancerre, six hectares in Puilly Fumé and 50 in New Zealand. In all they produce 30 cuvées in the Loire from 134 plots, all vinified separately.

Almost all of the winemakers visited on the trip vinified plots separately, had single vineyard cuvées, and wines that clearly made a big play of the soil type on the label – and tasting the wines there were clear differences between those hailing from flinty soils (silex), the chalky soils (Argile-Calcaire) and Kimmeridgean clay (Marnes Kimméridgiennes).

Famille Bourgeois which has been making wine in Chavignol for 83 years, sells a four-terroirs presentation box of wines with the soil types clearly marked and the fossils, flints and chalky stones embossed to help make the distinction clear.

The wines are sold at the estate next to presentation cases showing cross sections of soil types to draw the distinctions out. With more than 100 tanks in its new winery at Chavignol, it never mixes wines from different terroirs, even with entry level wines.

In Chavignol it also sells, Clos Henri Sauvignon Blanc from its winery in Marlborough, where exactly the same clones and winemaking techniques offers a unique tasting comparison between its terroirs in Sancerre with that of New Zealand.

Edouard Mogentti of Central-Loire’s governing body the BIVC (Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins du Centre) says that terroir-specificity is the key defining selling point of the region.

Edouard Mogentti, main manager BIVC “One of the priorities is to get more visibility, we know what we are but we have to make more of a distinction between the Loire and Central Loire.”

“It is important to communicate about Sauvignon Blanc but also to communicate about appellations – with Sauvignon Blanc you have a grape that works specifically with different terroirs and the grape will give its best in Central-Loire, Sauvignon Blanc is magnified here and made more beautiful.”

Tied up with all this soil speak and a recurring theme with the ten winemakers visited was how each feels the weight of responsibility of being a custodian of the soil and how, although all had an organic philosophy, many didn’t want to be fully AB certified on account of the use of copper sulphate and its long term effects.

Marc Thibault of Domaine de Villargeau in Pougny, Coteaux du Giennois is making 11 cuvées from his 21 hectares. Being organic is difficult with his terroir he says because of the amount of stones, although he says he ploughs more often to get more minerality into his Sauvignon Blanc. Current trends in his AOC he says are the amount of new, young winemakers and also climate change – the immediate downside is that it is lowering the acidity 3.8gms in 2018 where 5gms is the average, “which takes the skeleton out of the wine,” he says.

Improving quality and more textural styles

Central-Loire is primarily producing Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir with some Gamay and Chasselas thrown in for good measure.

The Sauvignon Blanc in this region is characterised by chalkiness, citrus notes (particularly lemongrass), mineral and saline, but there is a trend towards more textural styles developing. The quality from the entry level right up to the well known crus that we tasted seem to have taken a giant stride forwards. As with almost all global wine regions there is a younger generation of winemakers experimenting with different blended cuvées, whole bunch, longer skin contact, wood-ageing and so on.

Domaine Masson-Blondelet in Pouilly-sur-Loire has 17 hectares in Pouilly and four in Sancerre, so that they can produce a red (Pouilly-Fumé is a white wine only AOC). 65% of their wines are exported with the UK being their top market and the estate working with Waitrose for over 30 years. “We are not so dependant on the US market like some of my colleagues,” says Melanie Blondelet.

For wine buyers this is all great news as there is some smart buying to be done both in the better known appellations, with market-savvy, younger winemakers coming to the fore, but also in the less well-known appellations. Menetou-Salon has been a sommelier favourite for some years now but the quality in Reuilly and Coteaux du Giennois should not be ignored. We tasted fabulous wines at the home of biodynamic pioneer Denis Jamain in Reuilly and some very interesting reds at Domaine de Villargeau in Coteaux du Giennois.

Denis Jamain of Domaine de Reuilly is a biodynamic pioneer in Reuilly as well as head of the local trade association. He produces a range of single vineyard Sauvignon Blancs and Pinot Noirs as well as the Loire’s only Rosé made from Pinot Gris. Where only 15% of Reuilly’s wines are exported, Jamain manages 50-60%.

The Sauvignon Blancs can be simply outstanding from Central-Loire and the quality is improving in other parts of the Loire too – Touraine, in particular, where two new appellations have been created to raise the bar to premium level, in much the same way that Muscadet did with its emphasis on lees ageing a few years ago.

Blimey the reds are good!

The real surprise with Central-Loire, however, was the quality of the Pinot Noir. Loire Pinot has always been just wide of the mark in my mind, the wines often tasting too far over to the redcurrant side of the fruit, with green, unripe notes. Red Sancerre, for example, has always seemed somewhat anachronistic to me – and often regarded by the winemakers themselves as a diversion… and who can blame them when the Sauvignon is so good?

Jean-Dominique Vacheron says that he prefers making wines according to site selection rather than within a cru system, which does not exist in Central Loire. “We have no history of it, besides the cru system is too old it is not modern enough, it should be the consumers who decide where the best parcels are. I don’t like saying ‘this wine is premier cru’ but separate plots is much better.”

Many of the reds we tried on this trip, however, were world class. Particularly from Domaine Vacheron the estate that has cellars underneath the cobbled streets of Sancerre and has long been regarded as red Sancerre’s leading exponent.

The reds we tasted here were simply stunning – the Pinot originating from three main lieu-dits of Le Paradis, Les Romains and La Belle Dame, with the single vineyard cuvée from the latter to be on every serious Pinot lover’s list. Light, perfumed, structured with silky tannins La Belle Dame could easily be mistaken for a top Chambolle-Musigny.

All of the young 2018 we tasted from the barrel (which come from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti no less) had such power and a juicy core – well worth keeping an eye on when that comes to market, especially as there will be enough to go round from the 2018 vintage.

Jean-Dominique Vacheron says that 2018 gave such beautiful grapes – ripe, high in alcohol but also with great acidity “The balance is perfect.”