Fermented in oak and in acacia, left on the lees for a year, blended with Riesling and Chardonnay, undergone carbonic maceration… the changes to Txakolí are many and they are happening very quickly. We analyse what is happening plus list six of the best Txakolí to buy.

For years Txakolí (Chacoli) has been one of those wines that has steadfastly refused to go anywhere. It is inextricably linked to the Basque country that has always produced it, an autonomous region of Spain that has its own language, customs, sports, music, dance, cuisine and wine. The Basques even have their own name for Txakolí – Txakolina.

Txomin Etxaniz at Gaintza winery demonstrating the correct height to pour Txakolí into your glass.

Txakolí is a stubborn sort of wine, seemingly resistant to change, for the many centuries it has been made on this cool, wet Atlantic coast that has more rainy days than London.

Even today the traditional version of Txakolí – a frizante white wine of ferocious acidity, that is poured from on high to rid it of some of the CO2 – is still mainly made for and consumed by the Basque people.

Forget Txakolí producers trying to get international recognition for their wine, most will be thankful if they can manage to break it into other regions of Spain who themselves aren’t short of a wide range of unpretentious white wines that work well with seafood.

So why the interest in Txakolí all of a sudden?

An area of outstanding beauty, steeped in tradition

The first point to be made from a recent trip to the region is that Txakolí is a wine that could and should find a place with modern wine palates.

While Txakolí has stayed the same our tastes have changed and we have become more accepting of wines which are individual in style, which speak of where they are from and have a great back story. Txakolí is all of these things and also a food wine that matches fish and seafood with absolute precision. As such, it deserves a place on wine lists as much as un-aged Muscadet, Vinho Verde, Albariño and Alvarinho.

Tzakoli is an inexpensive wine, generally well made and would be just as much at home in a top metropolitan oyster bar as it would at a hipster hangout, alongside other quirky styles of wine.

Txakoli pairs well with vegetables, cheese and fatty, cured meats

The second point is that Txakolí wines are changing in style – in all manner of ways – almost as if the Basque people have reluctantly looked over their shoulders at Godello and the speed with which their neighbours have started garnering international attention and sales, slowly unfolded their arms and decided to do things differently.

It is a generational thing too that can be seen in wine regions across the globe where younger people start taking over the reins of the family winery and challenging the status quo with the knowledge and experience gained from their own travels and education.

Of the five wineries we visited across the three regions that make up the Txakolí DO all had an entry level/ traditional Txakolí wine and then one that was different – lees-aged, blended, Rosé, sparkling and late harvest – and significantly all had either young owners or young winemakers taking the reins.

“It’s Txakoli Jim but not as we know it” – carbonic macerated Txakoli

We even tried a Txakolí that had undergone carbonic maceration, Shoreditch take note.

Traditional Txakolí is normally made from destemmed grapes that are macerated before a two to three weeks fermentation in steel tank, the wine is then left on the lees for a few weeks or finished straight away and put into long, thin German Riesling-like bottles and is ready to drink, although most producers do leave it for a few weeks in the bottle. Originally Txakolí was made in giant wooden foudres but these are now more or less completely replaced by steel.

Depending upon which of the three Txakolí DO regions you are in, the wine is either still or has a frizante from the surplus CO2 and is made primarily from three grapes – solus or various blends of each. The most common style is for the wine to be made from Hondarrabi Zuri (white) with Hondarrabi Beltza (red) added to round off the very high acidity (8-11) and flavours. This is the style that the locals want and it retails for €3-8. A really decent bottle can be bought retail for about €5 a bottle.

Paying attention now?!

You could be in Greece

The wine has a pale greenish hue with citrus, green apple, saline and mineral notes. Some have a green, sappy quality not unlike some Greek wines. In fact, while we’re on that, the name Txakolí when written on traditional pewter jugs looks for all the world like Greek to me, with the whole Basque language full of TXs and Zs – predictive text had a nightmare trip let me tell you! This is all down to the fact that the Basque language pre-dates the Romance languages, hence why it is so removed from Spanish.

A decade of fast change: the new styles of Txakolí

For the last 10 years only, though, winemakers have been experimenting – leaving the wine on the lees for up to a year, fermenting in egg, concrete and barrel (oak and acacia), blending with local and international varieties, adding CO2.

The resulting wines on the whole are very exciting indeed.

Anna Martin Onzain, winemaker at Astobiza

Anna Martin Onzain, the first winemaker we met at Bodegas Astobiza is a consultant for a number of wineries in Spain and is credited for having made the first Txakolí wine to use extended lees contact. This is a wine called ‘7’ that she made when she was winemaker at Bodegas Itsasmendi and was a recent development – the first vintage being 2003.

Since then most Txakolí producers have started looking at diversification. All of the wineries we visited had extended lees wines, intended for the international market and also released in Bordeaux bottles rather than the traditional long thin bottles.

At Astobiza, Onzain is producing a traditional Txakolí, an extended lees wine and a late harvest stickie.

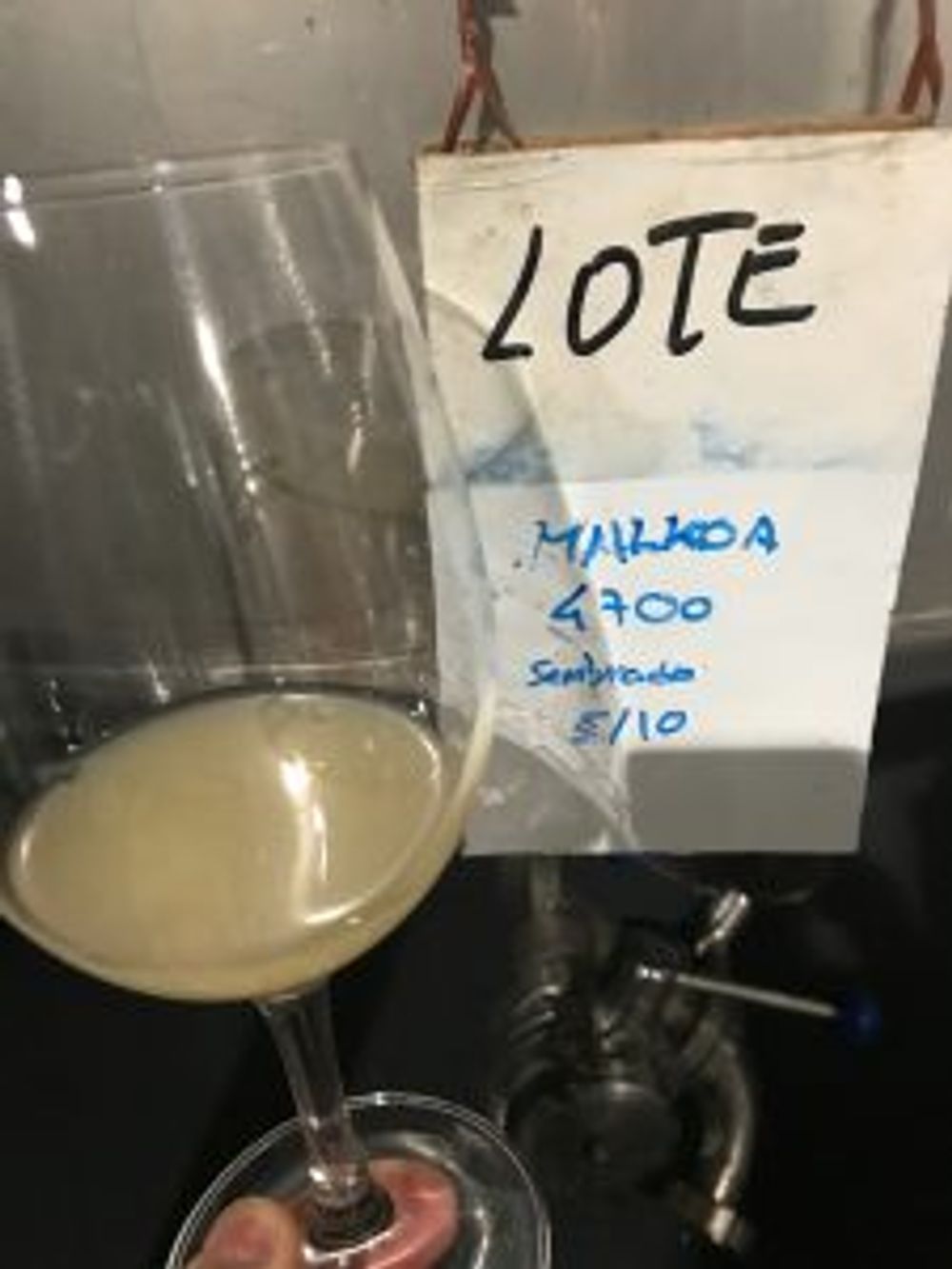

Hard work tasting unfinished Malkoa at 10am

The extended lees wine is called Malkoa that was first made in 2010. We tried the 2016 in tank and the most recent vintage released, 2015, in bottle. The greatest revelation though was on tasting the 2012 Malkoa which showed why the change in production has been so worthwhile – the wine had much greater depth and complexity but still retained the freshness, salinity and texture of the younger wine.

At Istasmendi itself, which we visited next on the trip, we found a winery trying a lot of new things including that carbonic macerated wine, that on the palate was a mix of ripe apple, bruised apple, caramel and wet stone, and was perfect as an unusual aperitif, matching the salted anchovies that are a speciality of the area.

The winemaking team at Istasmendi

Their top wine is clearly 7, a successful attempt by Itsasmendi to create a brand that is one part removed from Txakolí – no bad thing for international customers who cannot say the name of the wine let alone understand its many nuances. The winery gets plenty of Japanese visitors who revere 7 as a food-matching wine and are knowledgeable about the wide vintage variation you get in the region, partly a climate thing and partly the philosophy of the winemaking team here.

Of six wines I bought on the trip, three were from Itsasmendi a 2012 vintage of 7, the carbonic macerated wine and Artizar, a delightful blend of Txakolí and 20% Riesling which was really quite different – fruity, lifted, petrol, although the back label annoyingly didn’t mention the Riesling.

Mikel Txueka at Txomin Etxaniz – predictive text nightmare

Other changes we encountered on our trip involved fermenting a percentage of the finished wine in wood, the most interesting being a wine called TX, from Txomin Etxaniz, which was fermented in large acacia barrels, giving it a distinctive, fine-grained texture. The winery has recently been picked up by Gonzalez Byass for distribution in the UK and, although they haven’t decided finally on releasing TX here, I would bet that they succumb, it’s a terrific new take on Txakolí.

100 year old vines meet the sea – quite unique and very powerful

Txomin Etxaniz is the largest winery in the Getaria region, and with 600,000 bottles produced each year, accounts for 18% of the region’s output. Its location is gobsmackingly beautiful – with trellised vines of over 100 years old growing right by the Atlantic Ocean, adding to the salinity in the wine.

Txomin Etxaniz has also just started making a traditional method sparkling wine that had myself and other scribes on the trip reaching for their plaudits. Given the wine’s high acidity, this dry sparkler was a dead ringer for Champagne and should be looked out for, as and when it comes out of its limited on-site-sales-only production.

The traditional parra system which is slowly being replaced

Here at Txomin Etxaniz and at Gaintza, a smaller family-owned winery in the same region the change is also in how the vineyards are managed. Traditionally Txakolí has been grown on parra vines, which resemble the pergola system used for Albarino in Galicia. By carrying the vines well above the ground the parra system alleviates the humidity and resulting mildew that is a constant issue here.

The high rainfall means that with the parra system on slopes, the vines are allowed to grow into one another to form a protective canopy that will help prevent soil erosion. But, given the low annual sunlight, the canopy has to be constantly pruned back to allow the grapes to ripen – an unenviable amount of work in the vineyard.

Espalier vines at Artomaña Txakolina

Parra is slowly being replaced by modern espaliers trellises that are 30% cheaper to manage according to Gaintza’s, Joseba Lazkano, although parra is one area of tradition that is hard to turn your back on.

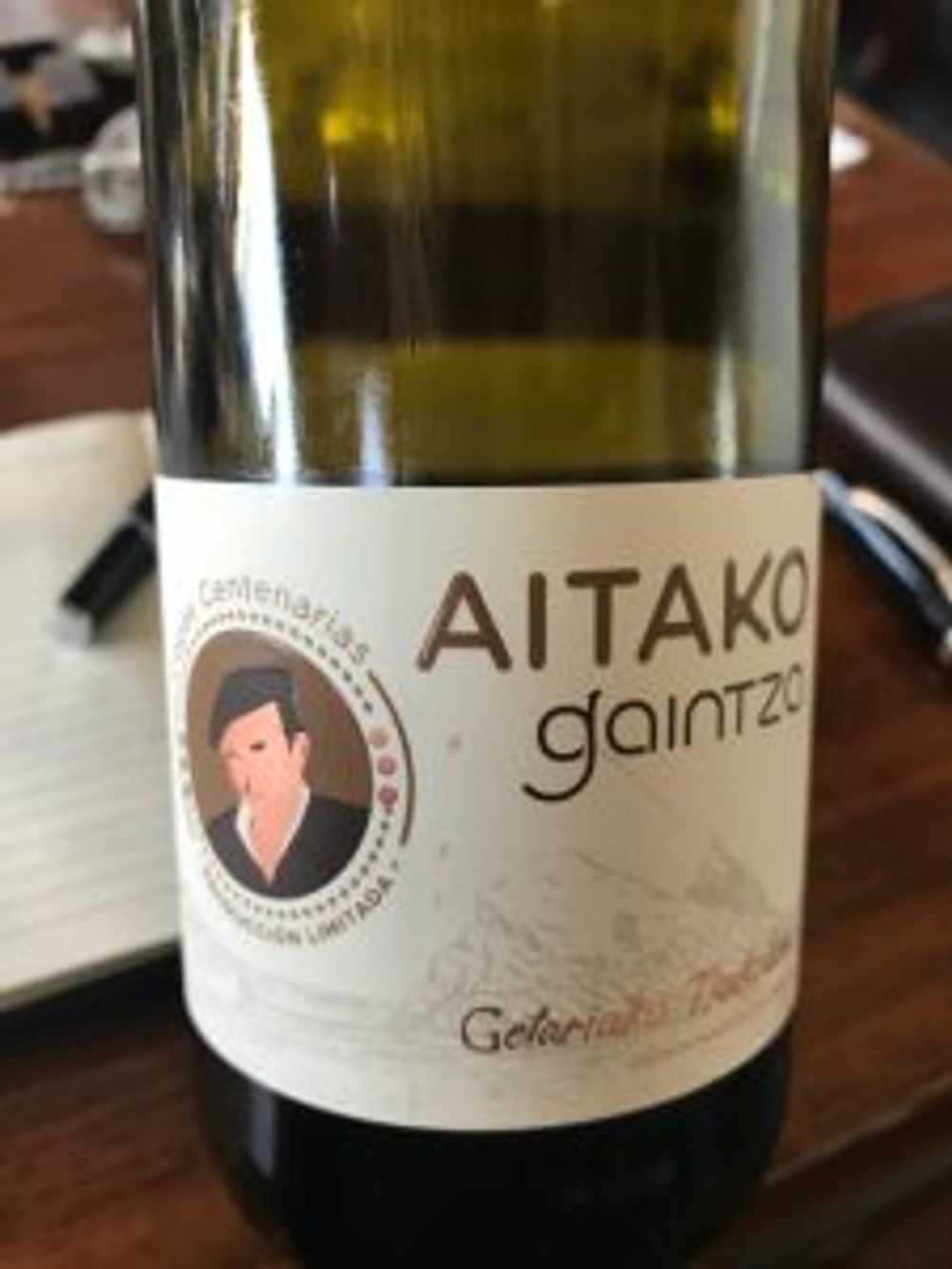

The vines at Gaintza were planted by Lazkano’s great grandfather, a giant photo of whom graces the tasting room wall – vines which were at a height where they could only be tended by being on your knees. Hard to uproot those for new stock.

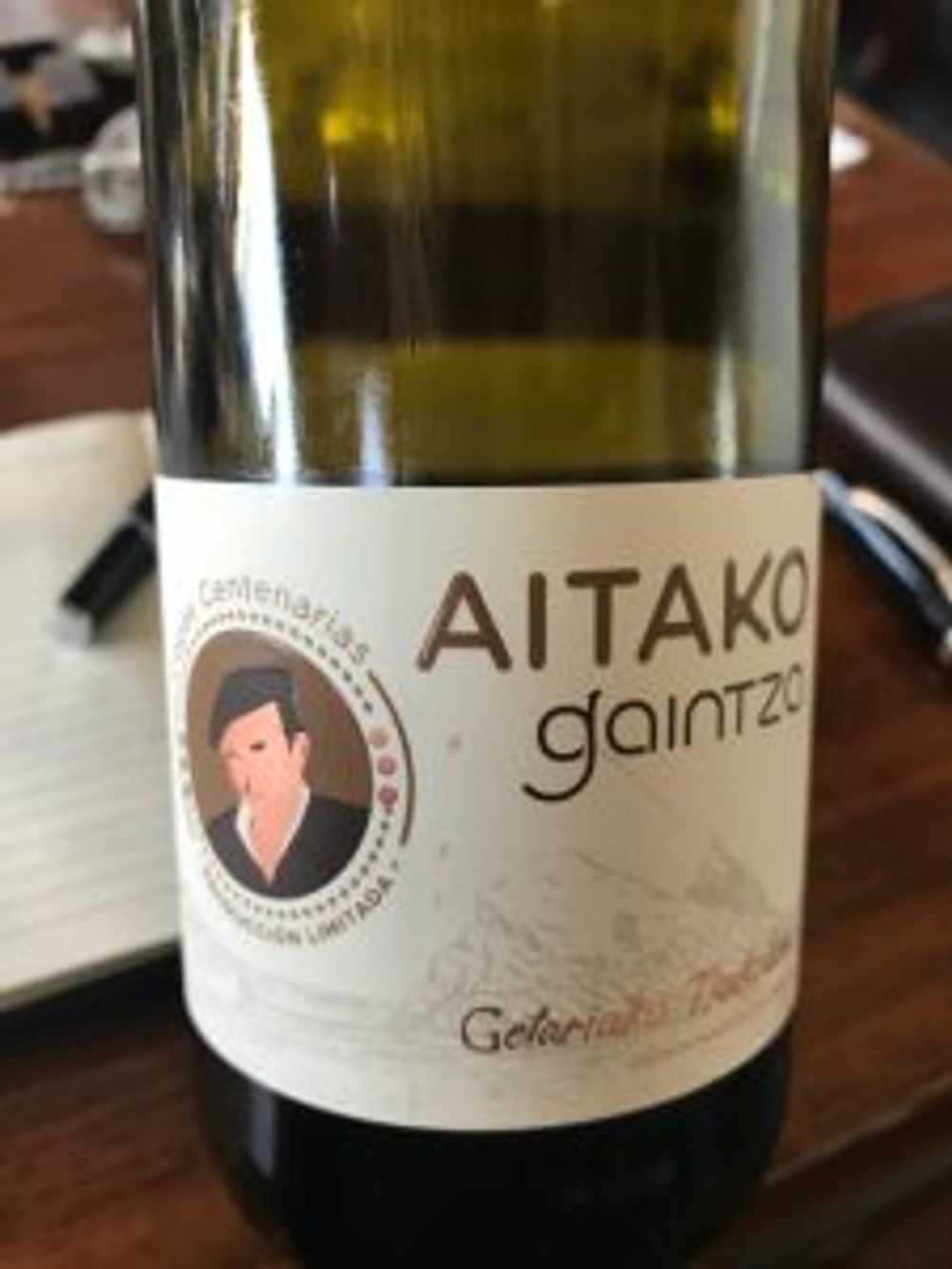

Lazkano explained that 90% of his Txakolí is sold to locals but that is beginning to change with him and his siblings overseeing a re-branding makeover to bring the winery up to speed – using modern, clean design and typefaces and giving the whole winery an impressive brand synergy. Aitako, the extended lees wine from Gaintza was a joy and, even though the labels have changed great grandpa is still on the label, although now in more Clip-art form.

Another very new development was at Artomaña Txakolina where a pipe at the base of the fermentation tanks pumps a five second burst of CO2 through the lees every eight hours for a total of two months – to replace any CO2 that may have been lost in the winemaking process and giving added fizz to the wine. This is the first year this experiment has been conducted – a development funded by the Basque government.

If you try just six Txakolí wines then these are the ones to buy:

Getariako Txakolina, 2016, Gaintza (Liberty)

This was my favourite traditional Txakolí from the trip, the first mouthful was like fresh sea spray – spritzy, saline, green apple sherbet. You would pair this with sushi, fish rice or have it on a traditional bar crawl called a poteo. (DO Txakolí Guetaria)

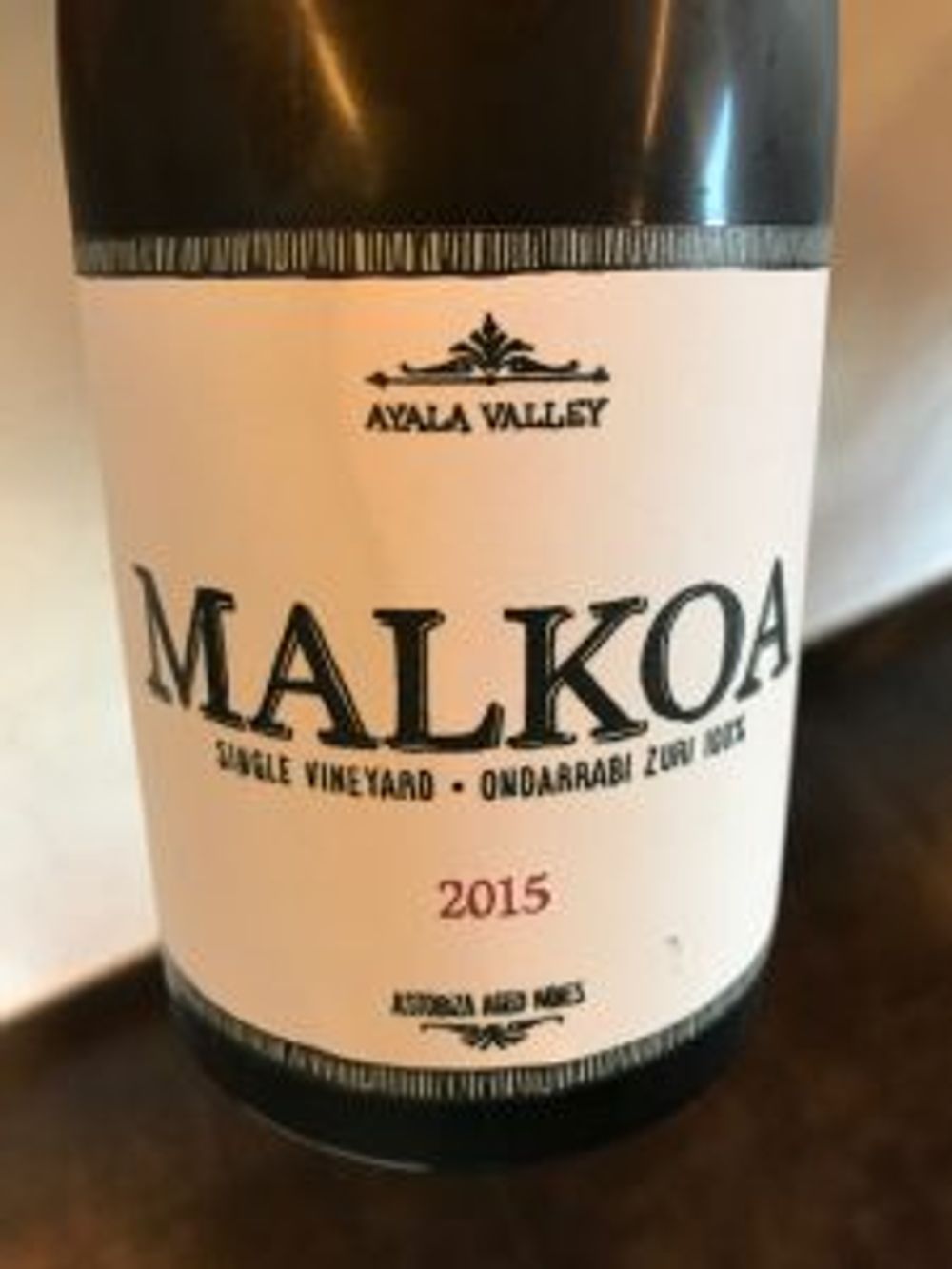

Malkoa, 2015, Bodegas Astobiza (various)

Astobiza’s entry level Txakolí reminded me of Greek varietals – with a slight pine forest, herby nature to them – and being from Ayala Valley in the DO Txakolí Álava the wines are still and non-zesty. This had texture, salinity and a bit of heat on the finish and delightful flavours of grapefruit and lime marmalade. From single vineyard 100% Ondarrabi Zuri and, helpfully, the label says ‘aged wines’.

7, 2012, Bodegas Itsasmendi (Alliance)

Try and get the 2012 but, to be honest, all of the vintages were good with some more outstanding than others. The 2012 was more gastronomic in profile. It had a hint of Gewurtz in the mouth but wonderful precision and focus. A real class act. (DO Txakolí Vizcaya)

Aitako, 2014 Gaintza (Liberty)

85% of this extended lees-aged Txakolí is made up of Hondarrabi Zuri (white) with Hondarrabi Beltza (red) and Chardonnay completing the blend. The wine has spent a year on lees and then another year ageing in the bottle. There is still lemon zest and spritz to the wine but it is much more subdued and disappears in the glass leaving a more rounded wine with greater depth

TX, 2016, Txomin Etxaniz (Gonzalez Byass)

Made with 100% Hondarrabi Zuri grapes that have had greater selection, this wine has much more body with a savoury, grassy side that complements the notes of citrus and melon. (DO Txakolí Guetaria)

Xarmant, 2016, Artimaña Txakolina (N/A)

Interestingly, we all preferred this winery’s traditional Txakolí over his extended lees aged wine. The translation of the name means ‘charming’ and it was exactly that – unpretentious, fresh with real minerality turned up. This is a wine where the winemaker produces a mass of customised labels. Not currently available in the UK but hopefully that will change soon. (DO Txakolí Álava).