As Argentina starts changing its Malbec style to leaner and crispier, so Rolland thinks this is a big mistake

The last time I had dinner with Michel Rolland I spied him using his mobile phone as a calculator. There was a very large figure on the display – with about 8 zeros on the end. It could have been him figuring out the Air Miles he had done visiting the 240 wineries he consults for worldwide, it could have been the amount of bottles his project in Armenia is producing. Most likely it was his annual profit and, if indeed it was, he would be the first person to admit it.

Irrespective of what your view is about Rolland – and everyone does have a view – the first thing that hits you is his disarming honesty and bonhomie. Ask him about replanting native grapes with international varieties and he tells you, ask him about his fruit-forward style of winemaking and he tells you, about Robert Parker and he tells you.

Michel Rolland would make a lousy politician.

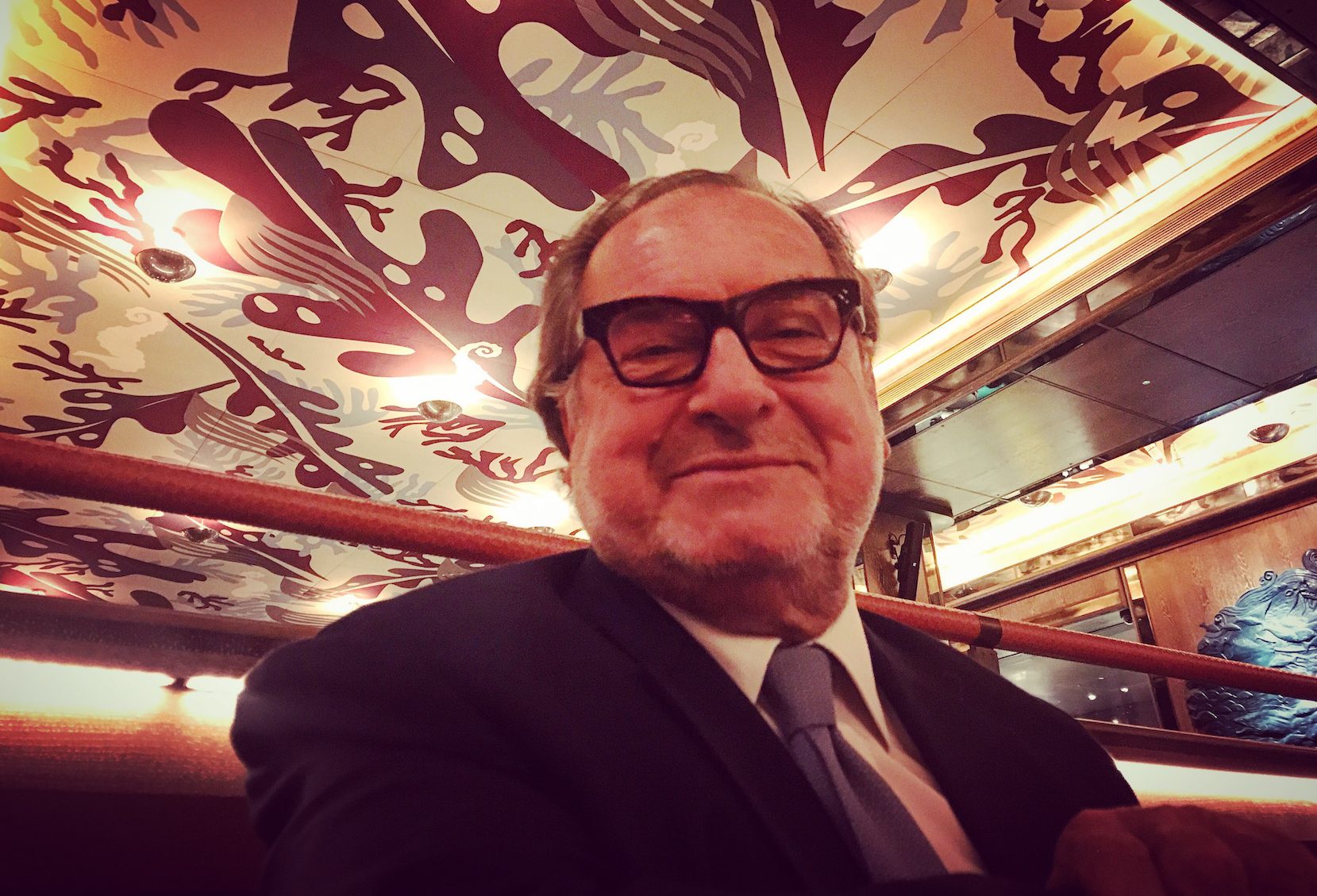

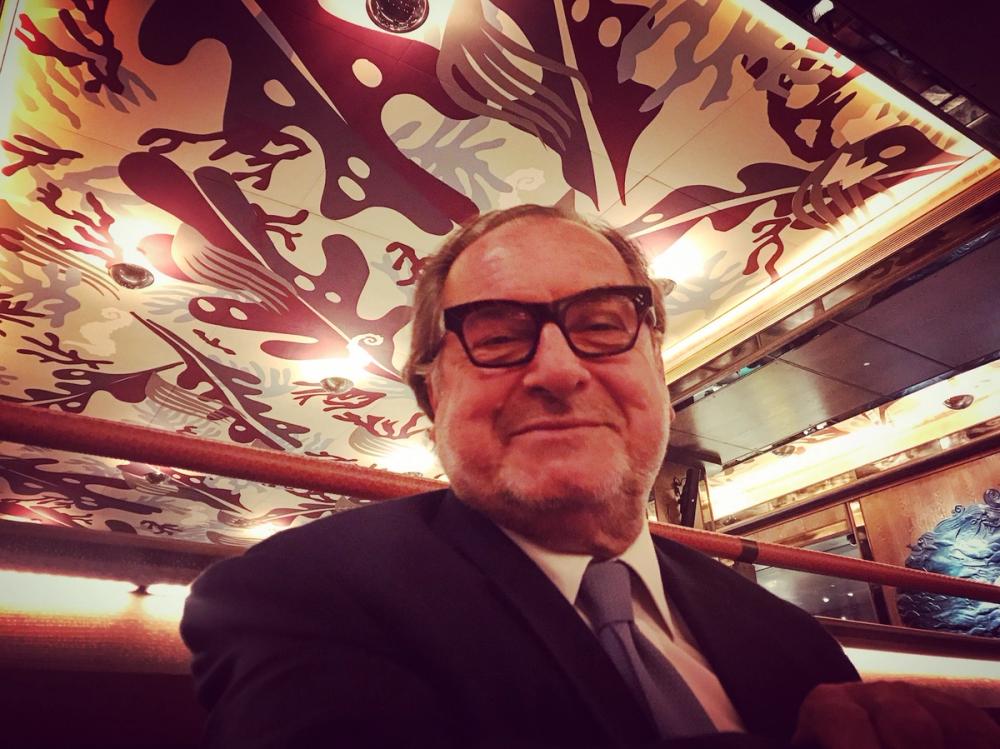

Michel Rolland, October 16, 2018, Sexy Fish, London

Today, at 71 years old with thick set spectacles and smart suit, Rolland looks more like a Harley Street consultant than a consultant oenologist (“Doctor, I’m having problems with my bunches of grapes”). Rolland is a man who seems at peace with the world, with little to prove; people know his winemaking style, his success rate is unequivocal… it is not for nothing that he is the world’s most successful oenologist.

Château Lagrézette and the lure of Malbec

We are in Mayfair’s Sexy Fish talking before a plush dinner at the recently reopened Annabel’s, alongside Alain Dominique Perrin, a friend and client of 30 years who, as the former head of Cartier from 1969, cut his teeth when Annabel’s was London’s first major nightclub. Do you think the bouncers will still remember you Alain? “Yes, I think so,” Perrin says with a twinkle, and then a flash of panic that he might not make it into his own party.

Alain Dominique Perrin and Michel Rolland

The night is in honour of the 30 years that Rolland and Perrin have been working together on Château Lagrézette, the Cahors-based winery that Perrin bought in 1979 with Rolland later drafted in to turn things around.

Rolland’s overarching strategy, of course, is to make wines that are ready to drink and enjoy as early as possible – fruit-forward, rounded with supple tannins – and to help professionalise a wine estate from planting the right grapes on the right terroir, through to making a product that is fit for exporting internationally.

“Bordeaux is always too old or too young but you want wine to be good when you open the bottle… even in Cahors. A bit crazy to gamble on Cahors maybe – it used to be square, harsh not very accessible, but now we do it round, supple and approachable,” explains Rolland.

“Malbec was there because it was good terroir for Malbec, it was a wine for the French market – but it was very high production with no real quality. So the question was what do I have to do? The terroir is there.”

Perrin bought Lagrézette in 1980 with 16 hectares of land with no intention of making wine. Now he owns 85 hectares 95% of which is vineyard across three terroirs and he has his friend Rolland to thank for that.

Château Lagrézette

“The first time I took the car to the vineyard I was looking and they were not doing good grapes, 70-80 hectolitres – huge – and they were not doing the right vinification, so we changed everything.” Rolland says. “At first Alain does not have a cellar, he sends the wine to the co-op. The man there says “I have two tanks for you, one 500 hectolitres and one smaller.” I can’t do anything with that.”

“Three years on there is a cellar, we are doing the right production, separation and choice for the vinification.”

One of the attractions for Rolland, apart from his love of challenges, was working with Malbec, a grape that features large in his portfolio of clients.

“Malbec grows so well in Cahors which is from the soil and the climate. It is not working so well in Bordeaux because it is too wet. In Cahors it is more continental which is why it grows so well in Argentina – they have continental conditions. Rain is a problem at every stage with Malbec, first at bloom season if you have rain there is no fruit, in the growing season and also when it is maturing you have rot. We have some family-owned Malbec vineyards in Bordeaux and it is always a disaster.”

“But in Cahors we are changing the reputation of Malbec. Before it only sold in the French market, in the ’50s and ’60s they were only looking for a drink, no-one was doing export. In the ’70s and ’80s they started doing export and started to improve the quality.”

The power of Rolland on exports: In six years the Chinese market has risen from nothing to 30% of sales at Château Lagrézette. (Perrin pictured in 2016 at the domaine).

So how does Malbec in Cahors differ to that in Argentina?

“It is important not to compare too much,” Rolland continues, “ for example Cabernet Sauvignon in Napa and in Pauillac, when put side by side one can be better, but that is not always the case. French Malbec, though, is more elegant, straight, with more acidity, in Argentina it is powerful and dense and a good feeling in the mouth – this is the style I like, but both can be good.”

In Argentina styles are changing with winemakers starting to head up the slopes and pick earlier, making a leaner, fresher style. What were Rolland’s views about this approach to Malbec?

“It’s a big mistake! And it will continue to be a mistake until the wine is good, but why make wine that is not good? The market doesn’t like it, you have to accept you have sunny conditions. In Argentina the wine used to be very bad, when I first went there they changed a lot of things – the picking date for example – but now they are making green again. It’s not my taste; I like a lot of different wine, but ultimately I am making wine that I like. It’s much easier to do it (to make a leaner style) than what we make.”

The proof is in the sales figures. At Lagrézette, for example, the Chinese market has risen from nothing to being the Château’s top export market in just six years, consuming a whacking 30% of the 400-500k bottles that they produce each year. The USA, Canada and Japan follow in importance with the UK described by Perrin as “an average market”.

Perrin (far left) and Rolland (far right) in the cellars at Lagrézette, 2016

Rolland on export, native grapes and looking after 240 wineries

So, apart from making wine that he likes to drink, is Rolland making wine mainly for international or domestic markets?

“I prepare wineries for export of course – my international reputation it is through export – I have to make wine that people will drink abroad. Who is making bad wine? Who can drink it? A handful of Bulgarians living in London who maybe buy two or three bottles every year, that’s not a business.”

Bulgaria, incidentally is one of a handful of countries where Rolland is now working because he sees the Black Sea countries as the ones to follow closely – he cites Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine and Georgia.

“I am working in Turkey with Vinero, in Bulgaria with Castra Rubra and with Karas in Armenia. We have planted a lot of grapes, Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, and for the white wines Chardonnay and a native grape, Kangun.”

So does he see it as a problem replacing native grapes with international?

“Look, I always try native grapes first until the wine is not good enough, but to stick with native grapes just because they’re native? That’s stupid. That’s the problem for me it’s very simple. It happened in Bulgaria and it happened in Armenia where we are making good wine with Kangun, if we don’t then we change it and make something good.”

Rolland has the same view with natural wine.

“It’s like what I said about native varieties… until they are good. If it’s bad wine then I am not natural.”

Michel Rolland: most at home with his nose in a large glass of Malbec

Rolland and his team of seven assistants now consults for 240 wineries, he does the blending for 70-75 wineries with an assistant, and looks after 27/28 wineries by himself. He says that having an open dialogue, often in real time, with the wineries is how he keeps up to date with what’s happening in all these vineyards.

Is it difficult hopping between the big clients and smaller ones?

“It’s the same, really,” he laughs, “one moment you are running a Formula 1 car, the next you are running a tractor, it’s all work but it’s different work.”

Rolland shows no sign of slowing down although, by his own admission, he is not desperately seeking new business as he once used to.

“I am not chasing the new contract like I used to do – but this man (Alain) and what he is doing is very interesting.”

Alain Dominique Perrin, Annabel’s, October 16, 2018

At the dinner Rolland and Perrin (sounding a lot like a TV detective series) show their mutual admiration for one another. Perrin calls it a “30 years love story,” while Rolland beams at him across the candle-lit room in Annabel’s, nose buried deep in a large glass of Malbec, a place you suspect he feels most at home.

Another good friend of Rolland’s, Robert Parker, has hung up his tasting glass for good now, his walking apparently not so great. “He’s the same age as me and I said to him ‘you are too young to retire’!”

As for Rolland himself there’s no sign of him throwing in the towel, a true heavyweight of the profession, he’s still getting the bouts and his fancy footwork is still pleasing the crowds.

So one last word from Perrin: “Before Rolland arrived at Lagrézette the wine was called Cahors, peasant wine, very harsh, bitter, now the wine is called Malbec.”

The wines and that dinner

Château Lagrézette produces 7 reds wines, 3 whites, a rosé and a stickie.

At dinner we tasted Le Pigeonnier White Vision 2015, Paragon Malbec 2015, Le Pigeonnier 2001 and Château Lagrézette 2015.

Spectacular place setting at Annabel’s

Le Pigeonnier is the top vineyard surrounding the Château and produces Malbec, the name coming from a 17th century dovecote on site; this wine is only made in exceptional vintages. Somewhat confusingly Le Pigeonnier White Vision, the estate’s top white is from Viognier grown many miles away in Rocamador. Paragon is a one block vineyard in Massaut with two different terroirs – gravels and clay-and-gravels. Château Lagrézette is the ‘premier cru’ of the estate, a blend of 87% Malbec, 12% Merlot and a touch of Tannat.

Le Pigeonnier White Vision was my wine standout of the night. A glorious well-balanced Viognier which matched the scallop carpaccio and caviar cream perfectly. The aged Le Pigeonnier was the standout red. The new reds were round, supple and atypical Cahors Malbec with supple tannins and an easy-going fruit core.