Italian wine lovers seem to be stuck on the Bs: Barolo, Barberesco, Bolgheri, Brunello di Montalcino, Barbera d’Asti and Barbera d’Alba – before they get to the Cs: Chianti and Chianti Classico. Or is that just an illusion?

“I’d rather be drinking Chianti”

Who actually drinks Chianti Classico these days? I wondered as we passed the gleaming new Antinori winery in the north-west of this famous DOCG region.

It might appear an odd question, given that this is a wine even most non-wine drinkers have heard of.

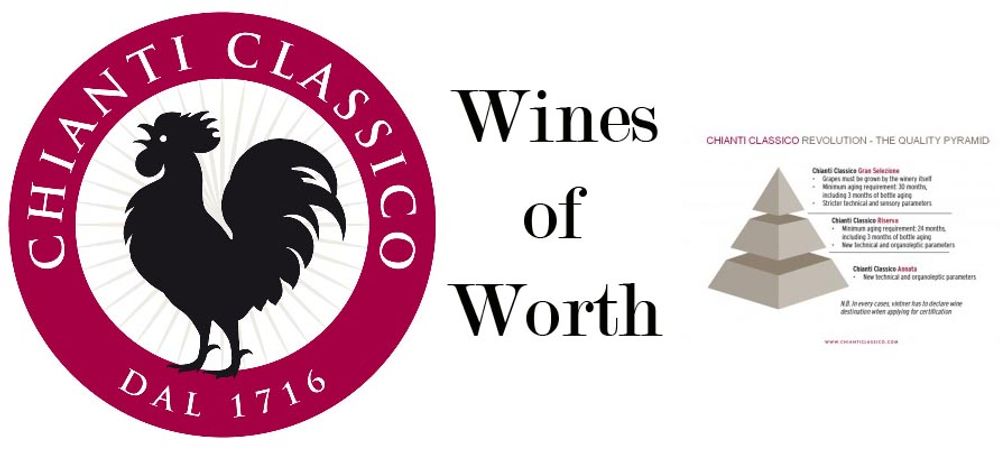

It famously hails from the beautiful hilly region between Florence and Siena – dubbed Chianti-shire because of its magnet-like appeal to middle class Brits – and is instantly recognisable because of the distinctive black cockerel that adorns every bottle.

And who doesn’t like their Italian meal washed down with a fine Chianti? Even if that meal doesn’t contain fava beans and liver and your name isn’t Hannibal Lecter?

But there’s the rub. Lecter was keen on a fine Chianti, but not necessarily a Chianti Classico. And over the past ten years lovers of fine Italian wine seem also to have bypassed it, apparently for anything beginning with B: Barolo, Barberesco, Bolgheri and Brunello di Montalcino are all now far more fashionable. Indeed, I would guess that even Barbera d’Alba or d’Asti – usually the second cheapest wine on the list at your local Italian restaurant – could give Chianti Classico a run for its money.

“God, I haven’t drunk Chianti Classico for years,” an Italian wine-loving friend of mine told me – even though Italian wines are the only wines he drinks.

Quite how unfashionable the wine has become was evident at the tasting held last autumn in London’s Royal Horticultural Halls – at which Chianti Classico producers showed their wines alongside other DOP products from Tuscany including olive oil, pecorino cheese and prosciutto (the last two overshadowed in the UK market by Pecorino Sardo and Parma Ham). It was deathly quiet, despite the absence of any other tastings in London that day, reinforcing the sense that the region is having problems attracting the UK wine industry’s great and good.

“It is ironic that once they started producing better Chianti, the wine lost many ‘aficionados’. With so many good Italian wines to choose from, Chianti has been relegated to the bottom of the pecking order,” says Gino Nardella, head sommelier at London’s Stafford Hotel.

For wine drinkers used now to New World styles, Chianti Classico is often, well, too much like hard work. Lots of acidity and Sangiovese’s often tough tannins don’t make for easy drinking. The fact that these are very much food wines (though quite how much so obviously depends on the winemakers’ style) doesn’t help them at tastings; nor does the fact a Chianti Classico from one producer can taste very, very different from one made just down the road. Sadly not often a pluspoint in this era of standardisation.

So what is the difference between Chianti and and Chianti Classico?

And then there is the confusion over Chianti and Chianti Classico: Chianti is the Tuscan region originally delineated in 1716 which today is often associated with wines of varying quality that famously used to put its wines into traditional fiascos (straw-covered bottles); Chianti Classico won formal independence from Chianti in 1996, although it has had its own Consorzio since 1924.

So Chianti Classico is Chianti but actually it sort of isn’t, despite being surrounded by the other seven Chianti regions.

Confused? Well, so was I.

I started my tour at the Casa de Chianti Classico, a former monastery outside Radda in Chianti, which the Consorzio uses to educate visitors to the region. It has done its best to define Chianti Classico as an independent DOCG, emphasising its distinct and strict production specifications, which include that its wines must contain at least 80% Sangiovese and no white wine (unlike the much looser regulations governing other Chianti sub-regions)

Located within an area of 70,000 hectares of which 10,000 bear vines that produce 35m bottles a year (a fraction of Chianti’s) the 580 consortium members must categorise their wine on the Consorzio’s Quality Pyramid, with Annata at the bottom, Riserva in the middle and, since 2014, Gran Selezione at the top (production of this last, most expensive category is small with only around 100 estates producing it, and has spawned its own controversy).

All three categories have clearly defined ageing, production and alcohol requirements, and the three wines I taste over lunch – L’Aura 2015 from Querceto di Castellina; the Castello di Gabbiano 2012 CC Riserva, part of Berlinger Blass and Castello di Rada Gran Selezione 2013 – all conform to this delineation, with the fresh but full on and vibrant L’Aura the most accessible, and the Gran Selezione the wine that clearly needs time to fully reveal its secrets.

So far so straightforward you would think, yet the confusion persists – at all levels.

“Do Classicos manage to differentiate themselves as a group from the broader ‘Chianti’ denomination? I’m not sure, but then I’m not sure either that the consumer knows or cares. They will follow a particular producer – which is broadly the case for Brunello and Vino Nobile as well,” says Charles Lea of Lea and Sandeman.

Valerio Marconi, head of sales and previously oenoligist at Cinciano, near Poggibonsi, says the ongoing confusion dampens sales.

“Buyers say why do I need your wine? I already have a Chianti. I then have to explain that Chianti Classico is not the same thing. This happens all the time,” he says.

The classic Tuscan view at Cinciano

Cinciano is all you feel a Chianti Classico winery should be. A beautiful location in a former 12th century hamlet, complete with medieval stone road leading up to it, it offers stunning views over the countryside. The current owner took over in 1983 and undertook massive renovation. He has also invested heavily in the wine; Cinciano makes around 130,000 bottles of six wines of which three are Chianti Classico, all made of 100% Sangiovese.

A tasting of these wines (available in the UK through Gastronomica) – shows clear definition; the Annata 2016 is well made with lots of character, and fruit drawn from a variety of vineyards. The Riserva 2013 is very vibrant, aged in large oak barrels for between 18-24 months, whilst his Gran Selezione 2013 is different again, full on and supple but with its best years very clearly ahead of it. These are great and well priced wines and full of local character.

Just around the corner, Castello di Monsanto shows another face of Chianti Classico. This beautiful property with impressive cellars and vintages dating back to 1961 certainly looks the part, and some of the older wines are great. Yet the wines they understandably show me (and other visitors here) are current vintages. But boy are they hard work! … tannic, hard, little fruit coming through, and expensive to boot. In a few years these will be delicious, supple and well-balanced wines but in the short term – which is when most of us drink wines – the fact they haven’t yet found a UK importer seems, somehow, unsurprising.

Further south, in a region famous for clay-rich soils, Rocca delle Macìe is a different, more commercial beast. Established by the late film producer Italo Zingarelli in 1973, and now run by his son Sergio, Rocca delle Macìe produces around 3.7m bottles from six six estates of which four are in Chianti Classico.

We taste five Chianti Classico of Rocca delle Macìe’s wines – Rocca delle Macìe 2016, the most important wine, around one third of total production; Tenuta Santa Alfonso a single vineyard wine first produced in 1985, quite forward in style; the Rocca delle Macìe Chianti Classico Riserva 2015, the Riserva di Fizzano 2015 single vineyard, and two Gran Seleziones: Rocca delle Macìe and the single vineyard Sergio Zingarelli 2014 Gran Selezione, 15% alcohol and already pretty full on.

This is the accessible, commercial more New World style of Chianti Classico and should find lots of happy consumers in the UK. Yet the wine – which in the 1980s and 1990s was a frequent sight at UK restaurants including Pizza Express – is only available in the north, since its main UK importer went bankrupt nine years ago.

“We are hopeful we can find another importer soon but it has not been easy – the UK market is very competitive and very price conscious,” admits Sergio Zingarelli.