“This was Armenia’s day and for me it shone brightly. It’s time these Armenian wines – and this small, ancient wine producing country – becomes better known in the UK and other western markets,” writes Keay.

Where was wine first made? Good question.

Several countries claim the honour including Turkey (eastern Anatolia), Iran (Shiraz) and Greece but the strongest claims are from Georgia and Armenia, with the latter arguably providing conclusive evidence with the discovery of the Areni 1 cave 15 years ago. Here in Vayots Dzor – today the largest wine region and home to Areni Noir, Armenia’s main red variety – archaeologists found remains of a wine press alongside ancient karas, the buried clay vessels similar to Georgian qvevri and still used for winemaking today.

Many Georgians dispute Armenia’s claim, reinforcing the long standing rivalry between the two, which made GInVino’s recent tasting at London’s Trivet restaurant all the more fascinating. The company, whose tagline is “Best Wines Off the Beaten Path” and which was established in 2014 by Zara Serobyan to focus initially on wines from her native Armenia, showed 40 Armenian and 49 Georgian wines.

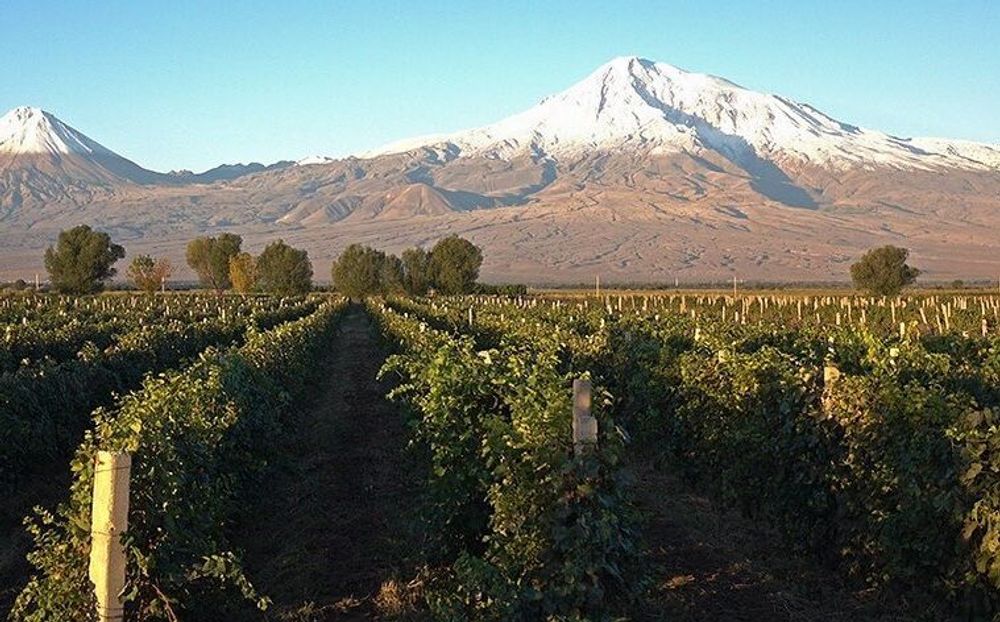

Stunning Armenian vineyards

“Armenian and Georgian wines are very different and not just in taste terms: they have very different soils and styles and Georgia’s industry is much bigger and capable of creating more volume. Armenia’s total annual production is probably less than what Georgia’s Kakheti region produces on its own,” she says.

As with just about anything in the South Caucasus, complexity is the key here. Both countries are Christian but differently so (Armenia is Apostolic, Georgia Orthodox) and each has a big problem neighbour (Armenia with Turkey which still contests its role in the 1915 genocide, Georgia with Russia which invaded it in 2008 and still occupies two of its regions).

As far as wine is concerned, both are focusing more on quality and western exports, but both remain dependent on the big Russian market, especially since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine made it harder for Russia to source wines from Europe and the US, and more inclined to turn back to what were always its traditional markets.

Qvevri winemaking at the Mildiani family winery

And there’s at least one other commonality. Although both are blessed with a wide range of autochthonous grape varieties – as you might expect with wine cultures stretching back millennia – 70 years of Soviet rule saw growers focus on just a few highly productive ones deemed ideal for the mass production (of wine and brandy) that defined the industry. In Georgia this was the full bodied, dark skinned and dark fleshed red Saparavi alongside white Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane; in Armenia, red Areni Noir (typically medium bodied, not unlike a Nebbiolo) and white Voskehat. Wine in the South Caucasus, therefore, remains defined by the decisions taken by central planners in the post war years – the old varieties remain dominant although the more adventurous producers are reviving and planting other indigenous varieties and playing around with styles and blends.

So how were the wines?

Just some of the Armenian and Georgian wines at the tasting, Trivet, London

Being familiar already with Georgian wines, like much of the UK trade, I opted to focus on Armenia, which has a much lower profile. This proved to be a wise decision because this GInVino’s is an exciting and eclectic range, and one likely to appeal to the on-trade: not only are all the wines likely to be unfamiliar to restaurant goers, attractive labelling and predominantly good back label information are another plus for those wanting to stretch their wine knowledge.

Starting with whites, I liked the Voskevaz Voskehat Kangun 2020, a fresh, fruit forward blend of Armenia’s best known white variety with a lesser known one, produced by Voskevaz Winery, the country’s oldest (1932) operating and best known producer from grapes grown at 1200m. Quite simple, but appealing with suggestions of white flower and peach on the palate.

More complex, and more pricey, the Voskevaz Karasi Collection Voskehat Vielle Vignes 2017 was really lovely. Made from grapes grown on 60 year old vines, the wine was fermented and aged on skins in clay karas to produce a rich and full bodied wine, suggestive of a good Viognier with perfect balance; apricot and peach on the palate, this is very moreish (rather more so than the 2016 of the same wine which was also being shown here).

Moving away from Voskehat, but not entirely, the Krya Indigenous White Blend 2021 (a well balanced mixture of Voskehat, Dolband and Garan Dmak (no, me neither) from the Vayots Dzor region, was an absolute cracker – the best white shown here, in my opinion. Very aromatic, with peach, jasmine and white herbs on the palate, this was very long and complex. Available this summer and well worth looking out for.

The imposing Voskevaz karas cellar

The Voskevaz Urzana 2019 is produced from a local Muscat grape, Muscat Vardabuyr and was pretty moreish, showing the usual Muscat aromas and flavours but quite dry, stainless steel fermentation apparently suiting the variety as well as karas: it’s worth trying this alongside the Voskevaz Amphora Blend Reserve white 2018, a blend of Muscat Vardabuyr and Voskehat, fermented and aged in karas, much richer and more complex but without the Urzana’s fresh immediacy.

There were just three rosé wines here and the most moreish for me was the simple but quite delicious Voskevaz Areni Noir Rose 2021, very fruit-driven with a long savoury aftertaste. Decent and distinctive and good value at around £17.

Amongst reds, the Voskevaz Amphora Blend Reserve Red 2017 a blend of Areni Noir and Hakhtanak – a dark, full bodied grape not unlike Malbec the name of which translates as Victory – from Vayots Dzor was very nice, well balanced with a long aftertaste and suggestions of dark berry fruit and chocolate.

Moving up the price scale, several vintages of Voskevaz’s high end range, the Karasi Collection Vielle Vignes were on show, (between £50-70 a bottle) including two Hakhtanak (2015 and 2018, from the Aragatsotn region) and three Areni Noir from Vayots Dzor, the award winning but now almost sold out 2015, 2016 and 2018. All were showing well but for me the 2018 of each were the stars, the Hakhtanak 2018 is a full-on wine, quite intense with suggestions of coffee and chocolate on the palate, and made from vines at least 60 years old, 1200 m above sea level, with a smokiness to the finish; by contrast the Areni Noir 2018 is a beautiful ruby red wine made from grapes grown on 120 year old vines planted at heights up to 1800m above sea level, with suggestions of intense dark cherry and berry on the palate. Elegant and very well balanced.

The range of high end wines from Van Ardi are also impressive, with a good quality/value ratio (around £35 a bottle). I really enjoyed the Hakhtanak Reserve 2018 Limited Edition, full on, meaty and berry-charged, whilst the Areni Reserve Limited Edition 2018 was a fascinating contrast; powerful yet also elegant, medium bodied with lots of complexity, this is clearly age-worthy.

The last of the reds I can recommend here – the Voskevaz Vanakan Winemakers Selection NV – is a delicious multi-blend of Areni, Hakhtanak and Kakhet, quite nuanced and characterful, the wine was released in 2015 to mark the centenary of the Armenian genocide by Ottoman forces during WW1. An elegant and worthy wine, seeing ageing in Armenian oak, with hints of vanilla and a long finish.

And last but by no means least, a wine made from one of my favourite fruits and one of Armenia’s national drinks. Pomegranate wine has been made in Armenia (and indeed other parts of the South Caucasus) for years and the Voskevaz Pomegranate 2019 is a fine example, 12% and made with the finest fruit grown in Syunik, in the south of the country. The palate is off dry and refreshing and the wine is a delightful light brick red colour. Something different and to be savoured, around £23 a bottle.

A good description indeed, of the tasting as a whole. The Georgian wines I did try were impressive, especially some of the quevri reds although some of the bottles checked in at over 2 kilograms – great for resistance training perhaps, but not the environment, and clearly aimed at the more blingy part of the Russian market. That said, I particularly liked the hefty – in all senses – Mildiani Private Selection Otskhanuri Sapere 2019 and the slightly lighter Mildiani Private Selection Aleksandrouli 2018, both complex, savoury but well balanced wines that provide proof that producers (and Mildiani is a big one) are moving away from just producing red wines from Saperavi.

But that’s for another piece perhaps. This was Armenia’s day and for me it shone brightly. It’s time these wines – and this small, ancient wine producing country – becomes better known in the UK and other western markets.

All prices given are retail. Wines available from GInVino.