Wandering through the streets of Chelsea that evening, I arrived early – intentionally. The spring air was brisk and fragrant, the architecture glorious. Beautiful townhouses lined the quiet roads, the kind that seem to wear their history lightly but with pride.

A Rolls-Royce Phantom 2025 parked as I crossed the road, more like a rhino than refined – too big, too robust. ‘Modern age,‘ I thought. Quite a contrast. Or is this just bling I’ve never quite seen the value in? All these thoughts swirled in my mind, surrounded by shops that felt overblown – clothes a tad too chic, prices a tad too high. Legacy or hype?

After my short spring walk, I stepped into The Cadogan Hotels' The Lalee restaurant passed through a bustling open kitchen where a team of sous chefs and waiters buzzed like ants preparing for the Queen’s arrival. I offered a smile and a hello in appreciation of their backbreaking work before entering a sweeping art deco alcove – a bright, high-ceilinged reception room with bay windows where the last rays of the April sun threw gold against the white walls.

Didier Mariotti, Veuve Clicquot’s Chef de Cave, in the kitchens of The Lalee

Outside, London buses decorated the view from the large Victorian windows – a touch of grit balancing the gloss. Inside: Veuve Clicquot Yellow Label Brut NV in hand. A first sip. That dry, citrusy acidity brought me back in the room – as though someone had pulled back a velvet curtain and let spring pour in.

I caught up with a few familiar faces from the wine world and soon, the waiters glided through with plates of edible sculpture – caviar, beef tartare, goat cheese – each one delicate and deliberate. I joked to Brad Horne, “My parents used to force-feed me caviar.” He laughed. “That’s the start of your novel.” Thirty years later, caviar hits differently. A thin crunch, then umami explodes, swept away by a wash of lemony bubbles.

And that was just the beginning.

La Grande Dame 2018 and the art of Pinot Noir

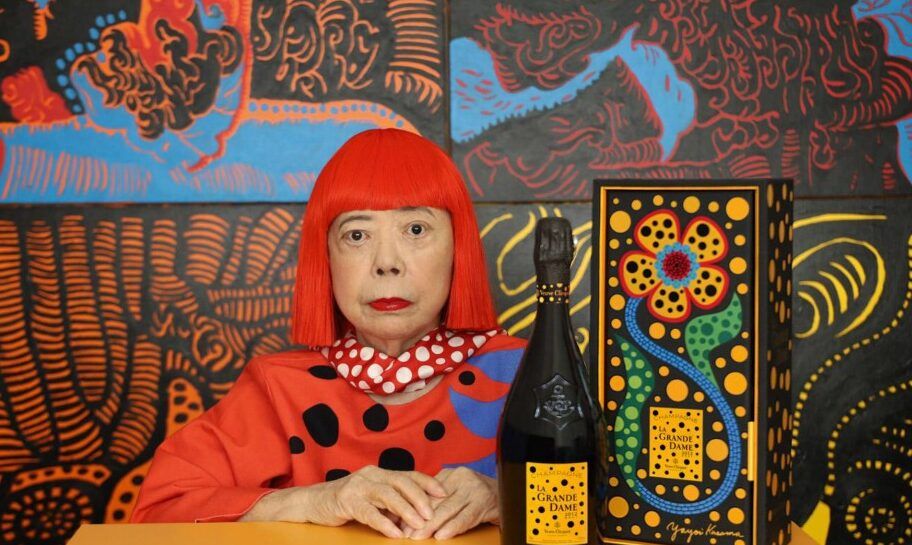

The evening was hosted by Didier Mariotti, Veuve Clicquot’s Chef de Cave, to mark the release of the 25th edition of La Grande Dame, from the 2018 vintage. The menu, crafted by Michelin-starred chef Luke Selby, reflected the Maison’s ‘garden gastronomy’ philosophy – rooted, seasonal, and quietly bold.

The first pour of La Grande Dame 2018 was a sensory exercise. Didier guided us through an unexpected experiment – tasting the wine in two radically different glasses.

"Just choose the glass you like most, and it will tell you a story.”

In the large Burgundy bowl, the wine opened up: broad, raspberry-rich, velvety. In the narrower wine glass, it became sleek and citrusy, revealing notes of lemon, red apple and white peach. "Just choose the glass you like most, and it will tell you a story,” he said. And he was right – it was like hearing the same chord in two different melodies.

With each sip, the 2018 showed off its detail: stone fruit and citrus peel, with a texture that was both taut and tingling. The wine walked a tightrope – elegant, vertical, and full of life, so very young still. Didier called it “a very precise vintage… sharp, elegant. Almost Blanc de Blancs in style.” That freshness was no accident – it was carefully preserved through picking dates and winemaking restraint. 2018 had followed a disastrous 2017, and with beautiful fruit came the winemaker’s challenge: “not to overdo it.”

La Grande Dame 2018 pairings

Dinner unfolded. The 2018 vintage made a confident first impression – bright and vivid, with the freshness and drive of a Côtes des Blancs Chardonnay, despite its 90% Pinot Noir composition. Paired with the beef tartare canapé, marinated to softness and melt-in-the-mouth lightness with laser-focused acidity, defined, almost electric.

Paired with sashimi of Scottish scallops, served raw with kaffir lime zest, coriander oil, and a cooling Thai granita. A sliver of asparagus added a green snap that mirrored the wine’s citrus edge. With La Grande Dame 2018, the pairing felt in harmony, each element crisp, linear and definitive.

Scottish langoustine followed, served two ways. The tail was poached in its own shell oil, torched, and glazed with a miso-chilli dressing playfully dubbed “chilli crack.” Beneath it, pickled kohlrabi and a sake-yuzu espuma added brightness and earthiness. The tempura claw, dusted with shichimi togarashi and served with shiso leaf, became a playful handroll, a tiny touch of heat with texture and gentle perfume. The 2018 held its line, drawing out yuzu, stone fruit, and spice.

A pivot in pace came with Cotswold chicken, served with sweetcorn and saffron gnocchi, and paired with La Grande Dame 2008. The wine had a more serious tone – richer, broader on the palate, with a rotund structure that unfolded slowly. A lean nose gave way to flavours of rubber, petrol, lemon peel and saffron, carried on a savoury, slightly smoky line. It moved with quiet weight – textural, expansive, but still pulsing with freshness. Didier called it “a wine with backbone, built for age.”

He spoke at length about reductivity, a winemaking approach that suppresses oxygen during fermentation and ageing, allowing the wine to evolve gradually and hold its tension. “I prefer reduction to oxidation,” he said, “because a reductive wine is shy. It makes you work for it. And it keeps its energy longer.”

In 2008, the acidity had been so sharp that they had to taste fewer base wines each day – “normally we taste 25, but that year only 15. It was that sharp.” But it’s precisely that acidity, married with careful reductive handling, that gives the wine its longevity and clarity, even more than a decade later.

The final act came with a pour of the 1996 La Grande Dame – a vintage that’s become near-mythic for Champagne lovers. Known as a “10-10” year for its rare balance of 10% alcohol and 10g/l acidity, it still feels youthful. On the nose: mango, toast, lemon oil. On the palate: electric energy, a sense of life that defies its nearly 30-year age. “It’s still a teenager,” Didier quipped, grinning.

Energy, elegance and legacy

“I don’t want wines that give you everything in the first minute. I want you to go into the wine. To listen to it. To let it evolve.”

Throughout the evening, Didier shared his personal philosophy. “A wine must have verticality,” he told us. “Even if a chair is comfortable, if it’s too low, it’s hard to rise. A wine must be raised first (in its structure) before it can develop complexity.”

Reductivity, for Didier, isn’t just a technique, it’s a philosophy of restraint, elegance, and patience. “I don’t want wines that give you everything in the first minute. I want you to go into the wine. To listen to it. To let it evolve.”

And when asked about his greatest challenge, he didn’t hesitate. “Legacy.” Not climate, not scale. “I want to leave vintages in the cellar that my successor will be proud to inherit – just like I inherited ‘96 and ‘08.”

It’s that same word – legacy – that had crossed my mind hours earlier on the street outside, wondering whether all that gloss and grandeur in Chelsea meant anything. Here, with Didier, the answer was clearer. Legacy isn’t about luxury. It’s about depth, intention, and time.

The dinner was a story told in bubbles, textures, acidity and conversation. From Chelsea’s polished streets to the minerality in the glass, the evening embodied both precision and pleasure. The tartare melted, the gnocchi glowed, the Pinot Noir – ever the chameleon – showed us just how many ways it can whisper, sing, and soar.

Legacy, it turns out, isn’t about age. It’s about energy.