“With increasing focus on cooler sites, more wineries with new ideas being established, and the addition of dry white wines to join the portfolios, the future of Ribera del Duero looks set to provide plenty of surprises,” writes Turner.

The last 40 years have seen the wines of Ribera del Duero come from relative obscurity to now being one of the most talked about wine regions in the world. In 1982, when the DO was first inaugurated, there were only seven wineries making wines from just 6,000 hectares of vines. Compare that to today’s 311 wineries and 26,000 hectares, and you can start to see the level of expansion that the region has enjoyed.

Within those producers, both new and established, sit some very committed and ambitious boys and girls that have spent recent years trying to understand the terroir they have to play with. Earlier this month, the UK wine press had the opportunity to hear from two such winemakers, Marta Ramas of Bodegas Valdaya and Jaime Suarez of Dominio de Atauta. Both are “first growth” producers in Tim Atkin MW’s Ribera del Duero reports, and he joined them online to discuss their current winemaking philosophies and what the future holds for this exciting region.

The climate of Ribera del Duero

Monasterio de Santa Maria De La Vid in Burgos

To understand Ribera del Duero, the DO consider four main pillars. The first is the climate, which is one of the harshest around in the world of wine. The local saying is that the annual weather is “9 months of winter and 3 months of hell”. Those long winters can reach as low as -20°C with the hellish summers easily achieving day time temperatures consistently over 40°C. It is super extreme and leads to a very short available growing season for the vines. That, coupled with invariably low rainfall that falls mainly in winter and spring, there is, as one wine consultant put it, “no such thing as an easy vintage!” Atkin himself divides the vintages up between the cooler and wetter Atlantic vintages (e.g. 2018), the warmer and drier Continental vintages (e.g. 2022) and also those vintages severely affected by frost (e.g. 2017).

Another big factor is the altitude. Vineyards range from 700m to over 1000m above sea level. It’s thought they are the highest vineyards in Europe outside of Switzerland. The vines of Dominio de Atuata range an impressive 930-1000m, with summer diurnal ranges of nearly 30°C. But it’s this altitude that gives the region a lifeline in the face of climate change.

“The moorland above the upper slopes is much cooler and very suitable for planting,” stated Atkin. “Any worries about struggling acidity or high alcohol levels can be well mitigated at these altitudes.”

The complex soils of Ribera del Duero

Altitudes of Ribera del Duero

One of the main reasons for the complexity of terroir in Ribera del Duero, is the soils. Atkin refers to the size of the area (around 125km x 40km) and the plethora of soils when he reflects on the comparisons with Burgundy. Although there are rough generalisations that can be made about the soils across the four communes of Soria, Burgos, Segovia, and Valladolid, much more work needs to be done to understand what’s going on under the surface.

“The region has about 30 soil types, with Vega Sicilia boasting 19 across their vineyards alone,” mused Atkin. “There’s no soil map yet, but hopefully one is in the works as it will really help understand the complexities.”

The variety of soils and the ability of the producers to work with the 7,500 growers across the region, allows for complexity in both single vineyard wines or multi-region blends. Bodegas Aalto is famed for its blending across region, adding complexity to its wines with the options of climate and soils. Some, including Marta Ramas, prefer to allow the soils of particular parcels to determine the wines they produce.

“Our Mirum wine is from vines on limestone soils near Baños that we think works well with concrete vats and Austrian oak ageing,” revealed Ramas. “On the other hand we produce our El Valiente using stainless steel vats and ageing in French oak. The clay soils at the plot in Sotillo de la Ribera produce rounder and more structured wines allowing us to play more with the oak.”

The land itself is a key focus for Suarez and his team at Dominio de Atauta in the eastern province of Soria. The Atauta valley is small, just 4km long and 1km wide, but even within that small space lies a depth of complexity. “We mange 56 hectares of old vines, with some over 200 years old,” continued Suarez. “Even within the 56 hectares, however, we split into nearly 700 micro plots, each with their own unique terroir. It’s my job to allow these wines to express where they’re from, not just my style.”

The grapes of Ribera del Duero

Old bush vine Tinto Fino in Ribera del Duero

The next of the four pillars are the grapes themselves. The region is dominated by Tempranillo, but few in these parts refer to it by that name. Tinto Fino or Tinta del País are the preferred monikers, not least to distinguish the superior clones from the lower quality, higher yielding clones brought in from Portugal, Italy, and Rioja in the boom planting years of the 1990s. Tinto Fino buds and ripens early, suiting the shorter growing season available, but its occasional lack of acidity is increasingly a worry as global climates warm. Harvests that used to need fires in the vineyards to keep pickers warm in the frosts of November are now happening in September.

In the face of climate change, however, Ribero del Duero has a secret weapon. Over 20% of planted material is known to be over 50 years old, with an impressive 8% over 80 years old. According to Suarez (rather tongue in cheek) the nematodes just couldn’t stick it what with the sandy soils and terrible winters, so many areas remained phylloxera free. Old vines, often planted as field blends or masale selection, are coping much better with the ravages of climate change, with deeper roots and lower yields to support.

Other grapes planted include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec, Garnacha Tinta and the exciting Albillo Mayor. Why exciting? Well, the DO has only allowed white wines since the 2018 vintage, and these must be 100% Albillo Mayor. It means we’re going to get to taste the experiments as they go from vintage to vintage.

“Albillo Mayor wasn’t new to us as it had been used in field blends, but we didn’t know anything about making white wines,” admitted Suarez. “There’s lots of experimenting going on with pressing, skin contact and blending. They’re coming out really well but so different. There’s no one style, everyone has their own and that makes it really exciting.”

The people in Ribera del Duero

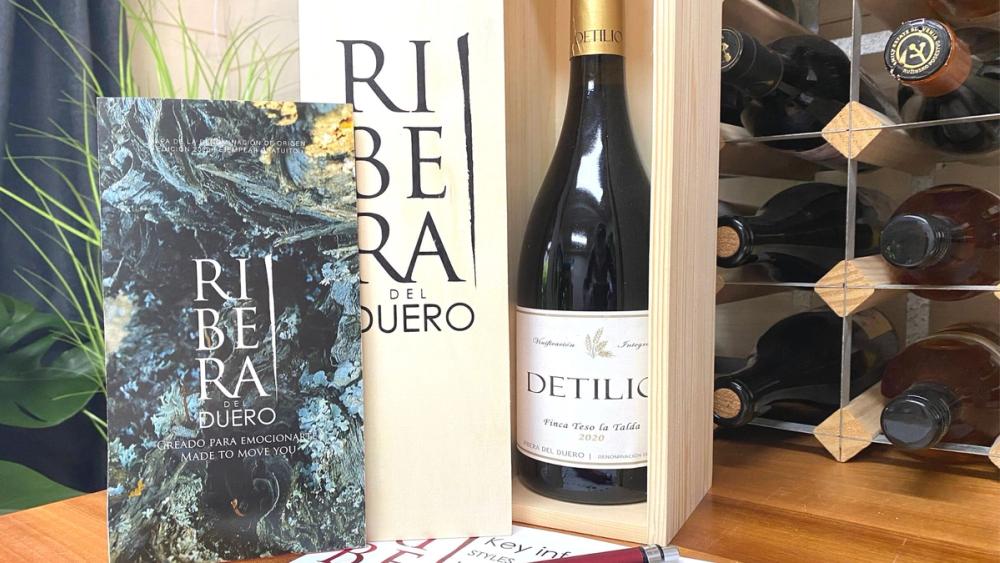

Ribera del Duero tasting kit from the masterclass

It’s the people of Ribera del Duero that have not only resurrected the wine industry since the dark days of the middle of the last century, but also are bringing new life and ideas to help shape the region’s future.

Between 1915 and 1965 Ribera del Duero was known as a low quality region. Wine books on Spain written in the 1940s and 1950s didn’t even mention it. Much changed with the establishing of Bodega Tinto Pesquera in 1975 by Alejandro Fernandez, and the subsequent rave reviews from Robert Parker of the 1982 vintage (the so called “Pétrus of Spain”) timed beautifully with the establishment of the DO in that year.

Subsequent generations have added styles to produce what they perceive to be the quintessential taste of Ribera.

Atkin breaks down the region into three different styles. From 1975 until 1990 there was the traditional style of wine, using American oak ageing in what was then a cooler climate. 1990-2009 saw the wine community, under the tutelage of a slew of wine critics, look for bigger, bolder, richer styles with plenty of French oak ageing, which became known as the modern style. From 2010, however, there is a new breed of winemakers who are aiming for freshness and subtlety, making vineyard-focused wines in lighter styles often using field blends.

“Whatever your tastes,” exclaimed Atkin, “there’s a Ribera for you.”

Marta Ramas is definitely one of the new breed. Trained in Bordeaux and having experience making wine across New Zealand, South Africa, and California, her challenge when accepting the role at Valdaya in 2013 was to provide an identity.

“People were looking at wines from Burgos and saying they tasted like a Rioja,” remembered Ramas. “We needed to look for the best plots, reflective of Ribera del Duero, that we could source and then vinify separately. It’s not that easy to find growers to work with, but when members of the family own great vines in Baños, and our cellar master’s family owns great plots in Sotillo de la Ribera, it makes it easier to work towards a goal of style.”

More to come….

Atkin remains enthusiastic about the future of the region. According to the MW, anyone who thinks Ribera del Duero is simply big, bold and heavy reds needs to take another look. With increasing focus on cooler sites, more wineries with new ideas being established, and the addition of dry white wines to join the portfolios, the future of Ribera del Duero looks set to provide plenty of surprises.

Marta Ramas is the head winemaker at Bodegas Valdaya, based in Burgos. Their wines are imported into the UK by Bancroft Wines

Jaime Suarez is the head winemaker at Dominio de Atauta, based in Soria. Their wines are imported into the UK by Boutinot

For more information about the wines of Ribera del Duero, please contact Claire White at Cube Communications on claire@cubecom.co.uk

Mike Turner is a freelance writer, presenter, educator and regular contributor for The Buyer. He also runs a wine events and ecommerce business, Feel Good Grapes, that explores and discusses the idea of sustainability in the wine trade.