“It’s a real tricky bastard of a grape, particularly when you are trying to make good dry wines,” one producer tells Justin Keay at the Furmint February 5.0 tasting.

Single Vineyard masterclass, Furmint February 5.0 event, London

Somehow it seems hard to believe that “Furmint February”, an initiative aimed at boosting awareness of Hungary’s best-known grape with a series of events including a London tasting attended by many of the region’s producers, is already in its 5th year here. So what’s changed over this time? – aside of course from Covid, war in Ukraine, earthquakes in the Levant, food shortages and all the other attendant horrors that now seem to constitute our new normal…

Well, for Furmint quite a lot. Five years ago, it’s a fair bet that few mainstream wine drinkers would have heard of the variety other than in the context of Tokaji Aszu, the famous desert wine that put Tokaj on the wine map centuries ago and is still rightly regarded as Hungary’s national treasure, or its cheaper cousin, Szamorodni (from the Polish word Samorodno meaning “as it comes), which comes in sweet or dry styles (the latter often tasting not unlike sherry).

And they had a very good excuse because dry Furmint only really became a thing around the year 2000 as producers, having restored the health of sweet Tokaji in the Tokaj region after the depredations wrought by 44 years of communism, turned their hands to dry wine. The reasons were largely economic: fewer and fewer people drink sweet wine, it’s very expensive and tricky to make and waiting for the requisite noble rot to develop is an anxiety-inducing business and potentially ruinous if this impressive but difficult grape variety refuses to play ball.

But today not only do most of the larger UK importers offer at least one dry Furmint but the wine can also be found on the shelves of Waitrose, Sainsbury’s and Aldi. Quality is very much on the up not only from the Tokaj region – Furmint’s spiritual home – in Hungary and neighbouring Slovakia but other regions like Eger and Somlo and further afield, Austria and Slovenia. And as producers try their hands at different styles – with single vineyard (Dulos) wines and sparkling, pet nat and even orange wines becoming more widespread – consumers are becoming more knowledgeable too.

“We’ve come a long way,” says Caroline Gilby MW who presented two masterclasses at the Furmint February 5.0 tasting on February 20. “When we started it was “Welcome to Furmint”, now we’re looking at single vineyard wines looking at the region and drilling down into its sites in more detail.”

Zsuzsa Toronyi, who heads up Wine Hungary UK, agrees.

“Over the years UK consumers have grown to know and like the variety, to the extent it’s now quite unusual to find someone unfamiliar with it. At consumer tastings – like the Wine Society – people love it and we’re getting great feedback.”

That said, there’s no escaping the fact that this grape – despite its wonderful smoky volcanic and apricot character – is difficult to work with due to very thick skins and high levels of malolactic acid in the juice.

“It’s a real tricky bastard of a grape, particularly when you are trying to make good dry wines,” was how one producer put it to me, admitting that this is why many producers blend it with up to 20% of Tokaj’s other white variety, Harslevelu, or put the wine through malolactic conversion to get a softer more rounded final product.

And tasting some of the 100 wines on show at Furmint February 5.0 made me realise that dry Furmint may be celebrating its 22nd birthday but is still very much a work in progress: although most producers were aiming for low residual/sugar, the styles varied enormously, so two Furmints with the exact low r/s and a similar ph could have very different texture and flavour profiles, one tasting almost austerely bone dry, the other more rounded and generous.

“I think the well-balanced, fruit forward wines are working best among consumers. They are also picking up the more ‘serious’ estate or single vineyard wines despite the higher prices,” says Toronyi.

One thing this tasting didn’t really show was how well dry Furmint ages – the oldest wines here was the delicious single vineyard Urban 73, 2017 from Szepsy, one of the best-known producers in Tokaj and a pioneer of dry Furmint and TR Wines Palota Furmint 2013, shown in magnum at the ‘Single Vineyard’ masterclass: a unique wine, never shown before, and rather impressive. But most of the other dry wines were from 2018 onwards, with quite a few from the just bottled 2021 vintage which Furmint February 5.0 was also showcasing.

But how would older Furmint show?

To discover how I subsequently tasted a remarkable range of museum wines produced by Puklavec Family Estates in Ljotomer Ormoz in north-eastern Slovenia, a producer which can date its origins back to 1934. Here Furmint – or Sipon as it is known here – takes on a very different more rounded and fruit-forward character. According to Tatjana Puklavec who says the variety has been grown in the region for decades, it still has to be handled carefully.

“Furmint has a high acidity when picked and the young wine needs a bit more time to settle down. Not every Furmint ages nicely and we have only been keeping the best wines from the best vintages in our cellar, with winemakers deciding which vintages have the most ageing potential. For us, this is learning by doing.”

For me too. Tasting through these old wines was one of my more recent wine joys, a surprise at pretty much every turn. The 1986 – a Spatlese with just 10.5% alcohol – was rounded, showing lots of herbal honey flavor, and a broad changing palate, with plenty of lively freshness supporting the residual sugar (17g/l).

However, for me the 1990 and 1993 wines were most impressive, not least because despite r/s of 8.9 and 10.2 these were both incontrovertibly dry Furmint: both deep yellow gold in colour, with some slight viscosity, they showed a hugely broad but mature palate, with rich honey, suggestions of marzipan and spice but also perfect balance and amazing freshness.

I kept looking at the labels to make sure I hadn’t made a mistake with the dates. But no – these wines were all 30 or more years old and tasting more lively than aged dry white wines from a famously tricky variety had any right to be.

Tatjana Puklavec admits the wines have been a revelation.

“We are very surprised to learn that they are ageing in such a lovely way, showing no old tones with a super lively acidity,” she said.

This suggests we can expect to see the same long-term evolution in some of the dry Furmint being made in Tokaj and elsewhere in Hungary, with producers now clearly getting into their stride with this tricky variety.

I’m not a betting man, but I would venture that Furmint February 6.0 will be focused on aged dry Furmints. Just a guess, mind you, but a good one – this is clearly a variety on a roll and there’s lots more to explore.

Six great single vineyard Furmints from Furmint February 5.0

Szepsy Urban 73, 2017 – (Tokaj)

Made from 65-year-old vines, this remarkably rounded and complex wine – and the others from Szepsy – were so popular that a scrum formed at the tasting table. This is classy, wonderfully balanced with lively acidity and lots of fruit, and ageing really well. (Top Selection)

Kovacs Nimrod – Sky, 2019 and 2020 (Eger).

Made from hand harvested grapes grown in grand cru vineyards in the region’s limestone soil (rather than Tokaj’s volcanic soil), this is another balanced but also quite powerful wine, with the 2019 showing 14.5% abv. A rounded wine with a broad palate, the r/s of 3 g/l was a surprise – I expected it to have more residual sugar somehow. A real class act. (Boutinot)

Pajzos Magyer – Furmint Selection Megyer, 2019 (Tokaj)

I liked all the single vineyard wines from this producer which produces from two historic vineyards, the 63-hectare Megyer and the 52-hectare Pajzos. On balance, my vote probably goes to the former, a slightly richer style maybe reflecting the addition of some Harslevelu to produce a well balanced and rounded wine with just 1 g r/s. Barrel aged for 6 months, there’s a a complex palate here with notes of almond, some marzipan and pear. (Malux)

Barta Winery – Oreg Kiraly Tokaji Aszu 6 Putonyos (Tokaj)

There were gasps when this was shown at the end of Caroline Gilby’s ‘Single Vineyard’ masterclass and some were from me, which is why this is the only sweet wine to feature in this otherwise dry Furmint-focused feature. Gilby said “this demonstrates what Tokaj balance is all about” and I couldn’t agree more: there’s great salinity here, with good balance and, despite 245 g r/s, this is not at all sickly. A wine to make you just sit back and wonder. (Corney & Barrow)

TR Wines – Organic Pet Nat, 2022 (Tokaj)

Another great producer making a wide range of wines from the Palota vineyard, many blending Furmint with Harslevelu. I could have chosen any of iots wines for this list but the Pet Nat was fun, fruit forward and just delicious. A style with a future, I would say, from a dynamic young team that clearly knows what it’s doing. Why this producer still doesn’t have a UK agent is something of a mystery. (Looking for Representation).

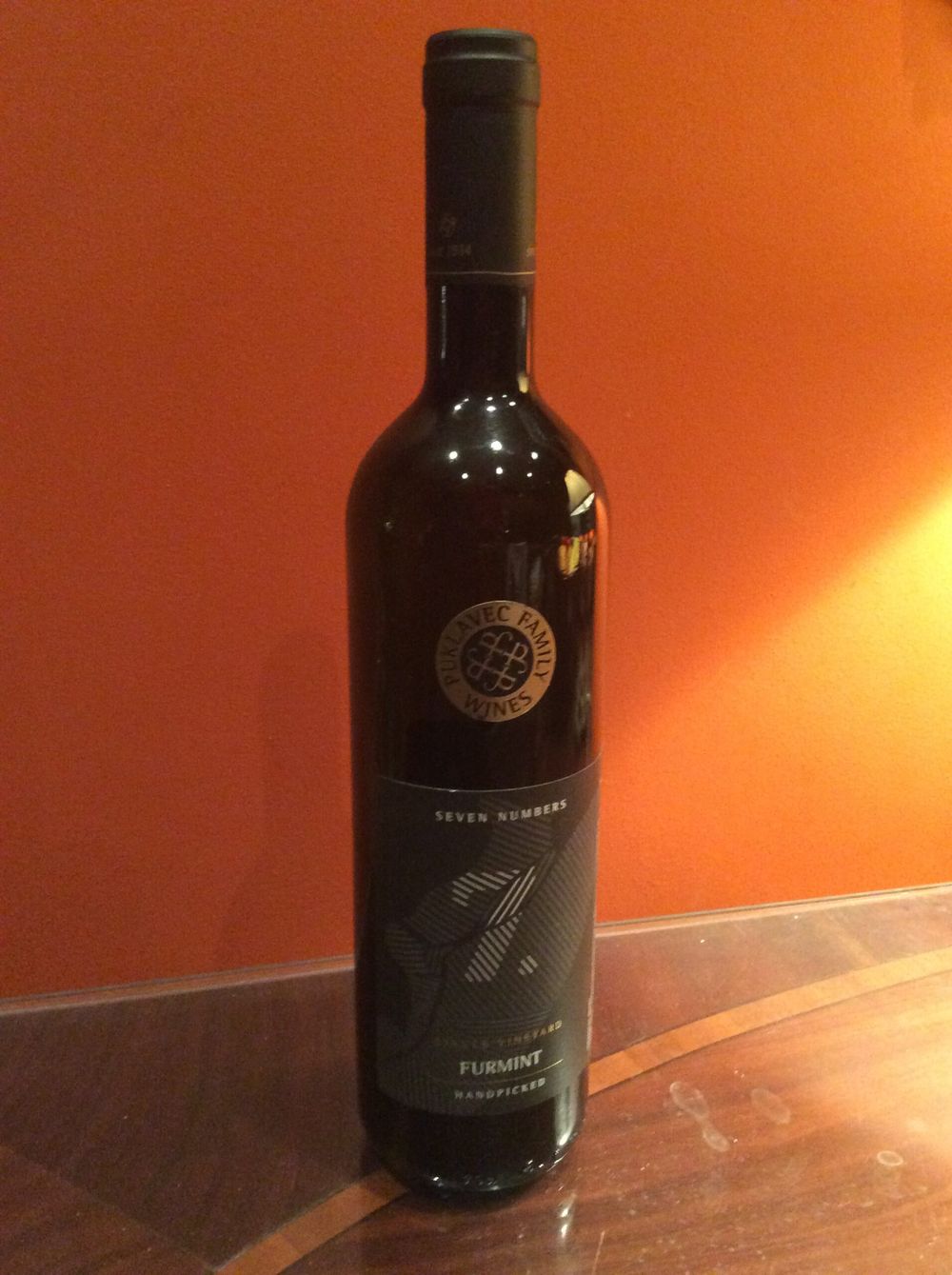

Puklavec Family Wines – seven numbers 2015/2019 (Slovenia)

I’ve tasted two vintages of PFE’s single vineyard wine (the 2019 at the Bibendum tasting) and loved both but the 2015 shows both the longevity of Furmint (or Sipon to give it its correct local name) and how it differs from the grape in its more familiar Hungarian context. Just 4500 bottles were produced from handpicked grapes grown in individual blocks marked with seven numbers to enable the grapes to be traced back to their origin. This is full bodied, 13.5% with a distinctive, spicy and herbal palate that evolves in the glass. Complex and moreish, to be tried alongside some of its Hungarian counterparts. (Bibendum)