“Numerous blind tastings between winemakers had concluded that the winemakers themselves couldn’t tell which wine was from which region.”

“Nothing worth doing is generally easy,” Jeremy Dineen said, leaning over to fellow winemaker Peter Caldwell to his left, who had just explained how hard viticulture was in Tasmania. Both men and Rebecca Duffy, who made up this trio of Tasmanian Pinot Noir makers, burst out laughing.

Tasmanian Pinot Noir webinar, November 19, 2020. Duffy, Dineen, Caldwell (l-r)

The fact that making Pinot Noir in Tasmania is completely worth doing was blindingly obvious to anyone tasting the six wines that accompanied this live webinar. With every vintage, it seems, the wines from Australia’s island state seem to get more and more assured, which is hardly surprising when you consider that they have only been growing Pinot seriously here for less than 40 years.

“You only get one shot at making wine very year so I have only had 14 goes at making wines here,” said Duffy, co-owner and winemaker at Holm Oak, “there are a lot of clones, a lot of options, it’s working out how to do it – how to deal with the climatic challenges – it’s a lot of fun but really challenging.”

It is that challenging environment that led to a complete absence of any vineyards on Tasmania between the mid-1800s and 1956 when the first vines were re-planted.

“The general wisdom was that it was too bloody cold to grow grapes in Tasmania and now everyone wants to be here,” said Dineen.

Sailor Seeks Horse vineyard, Huon “The greatest viticultural challenge I have ever seen” was the assessment of the viticultural liaison officer from one of the big wine companies.

Fast development and regional differences

Although vines did appear from the 1960s through to the mid 1980s, the modern wine industry as we know it didn’t really get going until 1985 when Roederer and Tasmania’s Heemskerk formed Jansz, which cemented Tasmania’s future as a producer of world class sparkling and, elsewhere, grape growers had moved away from planting Cabernet Sauvignon to Pinot Noir.

At that stage there were just 47 hectares of vines on the whole island, producing a mere 11,000 bottles. Today that figure is over 2000 hectares producing almost 900,000 bottles which is a figure that is steadily increasing as the world wakes up to the quality and value found in Tasmanian wines.

“We still haven’t discovered all the sites where we can grow great Pinot,” said Dineen.

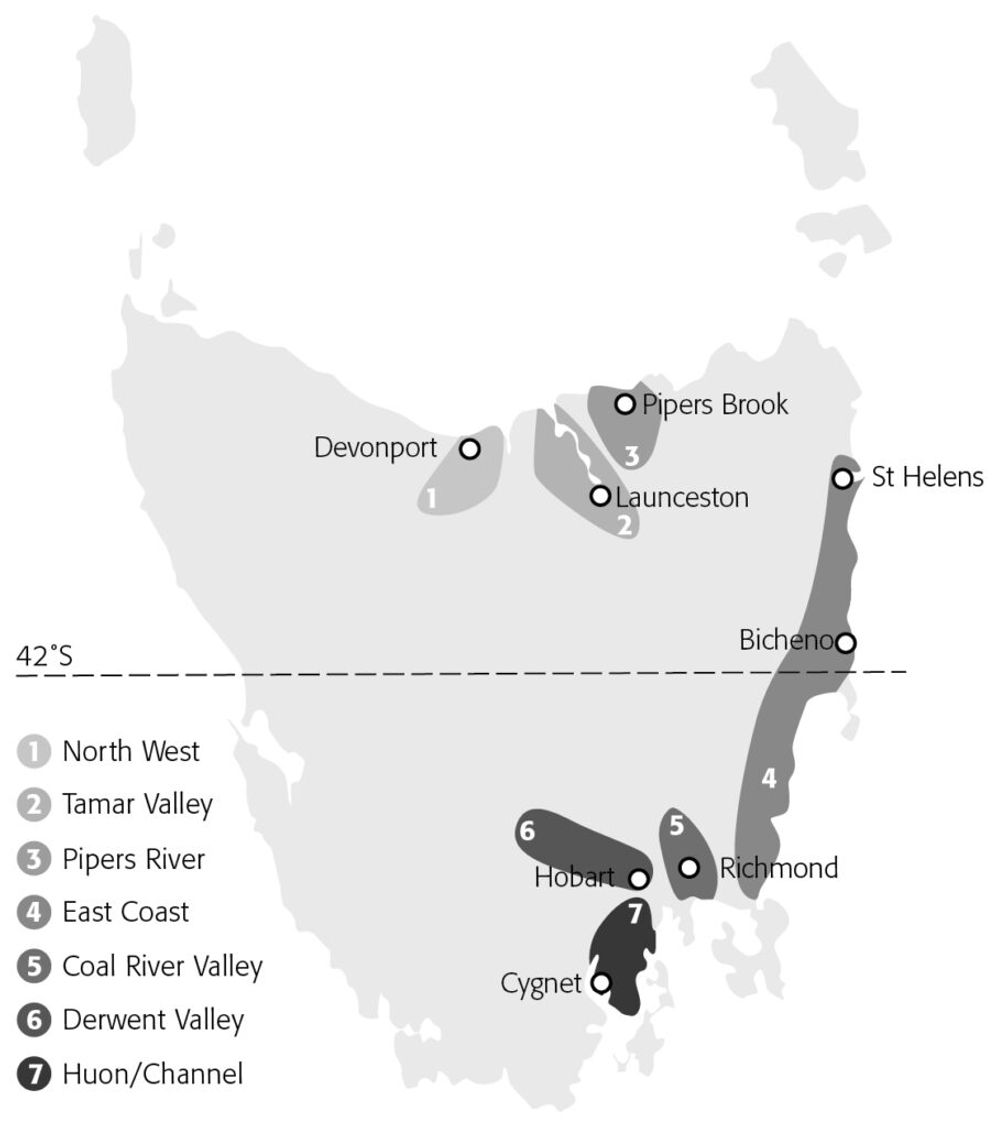

Whether new sites will be commercially viable remains to be seen. The Pinots we tasted came from six of the seven recognised wine growing areas on the island, one of which, Sailor Seeks Horse, is made in the ‘marginal region’ of Huon Valley from a mere 2.6 tons per hectare.

“I would be crying if I got that,” said Peter Caldwell.

Although there were clear differences in the style of the six Pinots we tasted, the recognised wine growing areas will not be formally designated as separate sub-regions any time soon, according to the panel. They pointed out that Tasmania makes less than 1% of all Australian wine and that, although they could make broad generalisations about the difference say between Pinot grown in the Tamar Valley compared to Coal River Valley, numerous blind tastings between winemakers had concluded that the winemakers themselves couldn’t tell which wine was from which region.

“We love telling the story about the intricacies of our own sites and our own sub-regions but modern viticulture here is only 50 years old and for the majority of consumers it is too early to tell that story,” said Dineen.

“Besides, one of our strengths is that we collaborate together as Tasmania,” added Duffy.

“Nothing worth doing is generally easy,” Jeremy Dineen, GM and chief winemaker Josef Chromy (pictured before ‘Lockdown hair’)

Tasmania’s soils are dominated by Jurassic dolerite and are famously varied, along with the rainfall and climate. The 26thlargest island in the world, Tasmania sits between 41 and 43 degrees latitude, is wild, rugged and remote. Forgetting the small island to the north of it, there is nothing west for 14,000 kilometres and just Antartica due south. Like New Zealand’s South Island, the west coast of Tasmania collects most of the rainfall leaving the central and eastern parts of the island drier.

Warmer vintages are becoming more common, but Tasmania looks well placed to avoid the effects of climate change in the short term, in its warmest spot there are maybe 3-5 days where temperatures exceed 30 degrees, but for the most part it is a moderate climate.

Chief grape growing areas of Tasmania

As for the wines…

Three of the wines were from 2017, three from 2018. What you need to know about recent vintages here is that 2016 and 2018 were warm vintages with high yields and slightly lower acidity in the wines, 2017 and 2019 are cooler vintages with lower yields. Where the wines from 2018 are elegant, ripe, juicy, aromatic and approachable at a very early stage, the weather in 2017 led to smaller berries, with the wines being denser, darker and more structured. Both 2016 and 2018 were excellent for sparkling, according to Dineen

Although there were many differences between the six wines, common characteristics of them are: high-toned aromatics; bright acidity (from Tasmania’s slow ripening period); fine tannins; freshness; great balance; elegance; light ruby red/ purple colour and predominantly red fruit. They all showed well, were of a high quality and deliver a lot of bang for your buck, especially compared to Burgundy, which a couple of these wines could easily be mistaken for.

Wines in order of tasting:

Tolpuddle Vineyard, 2018

Limpid, light ruby red/ purple; fine aromatics (red fruits and floral); open, fresh, nice fine texture, good balance between fresh fruit and acidity, 40% whole bunch giving a bit of grip. Light and quite delicious. (Liberty, £49.99 rrp)

Tamar Ridge, 2018

Red fruits (strawberry), floral; light and fresh palate; 20% whole bunch; light, fresh, precise, focused, bright with a lovely register on the palate – mild citrus and fine grained on the finish. (ABS £23 rrp)

Holm Oak Vineyards, 2018

Very light ruby red; attractive strawberry/ floral aromatics; light and fresh; fine silky tannins, bright, lively acidity, touch of spice. (Villeneuve Wines, £20 rrp)

Josef Chromy Wines, 2017

Riper entry point, more black fruit (cherry), more intense, farmyard/ sous bois; More structured, textured, greater concentration, grainy texture, feels like higher acidity than wines 1-3, slightly toastier. (Bibendum, £24 rrp)

Dalrymple Vineyard, 2017, Dalrymple, Pipers River

Rich nose, mix of blue and black fruit, spicy component (cinnamon), green pepper. Fresh, bright, concentrated fruit flavours, but fresh, lifted acidity, fine tannins, fine-grained oak texture. (Fells, £33.99 rrp)

Sailor Seeks Horse, 2017

Much greater complexity on the nose, best of the bunch, really Burgundian – ‘stand-out’ fine wine; interesting savoury component, lovely balance, mix of red and dark fruit, lean, complex, great texture/ acidity balance; could easily be mistaken for a top site in Côtes de Nuits (The Vinorium, £44.50 rrp)

Just for the record: Peter Caldwell thought he could sneak in without us all seeing him arrive late!